This essay is an amended version of an earlier one that was posted here on September 30 in 2023. Special thanks to Marcel Lang, for helping with the presentation. In this essay we discuss Ice Hockey’s birth and earliest evolution, until around the end of the 19th century. This presentation builds on an earlier essay that was published in late 2021 which can be found here. It’s a one-person project, presented by a ‘yours truly’ who sometimes refers to himself in the plural, and uses Capital Letters to refer to the sport in general. Our “Ice Hockey” includes all variations of the modern game which these essay show can be sourced to one location based on very straightforward history. For more specific versions of “Ice Hockey,” we use phrases like “Montreal ice hockey,” NHL ice hockey, women’s, junior and Olympic ice hockey, and so on.

INTRODUCING “HALIFAX”

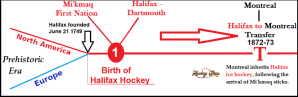

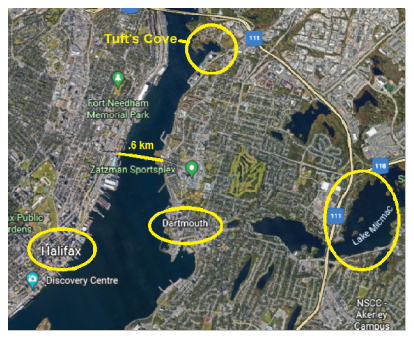

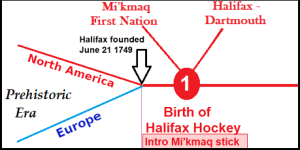

In recognizing “Halifax” as the 2nd Star of the sport of Ice Hockey, we refer to the colonists of Halifax and Dartmouth. Our 1st Star were the Mi’kmaq First Nations members who lived in the same area, which they called Kjipuktuk. We shall sometimes refer to them as the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw, and sometimes call Halifax Halifax-Dartmouth-Kjipuktuk, or some such thing, to remind the reader of Halifax’s other two partners.  We present our Stars in order of their known appearance only, with no regard to how stars are usually awarded in Ice Hockey. The main thing to know about our first two Stars is that they formed a partnership that fueled the rise of what became Canada’s culturally dominant version of Ice Hockey in the 19th century.

We present our Stars in order of their known appearance only, with no regard to how stars are usually awarded in Ice Hockey. The main thing to know about our first two Stars is that they formed a partnership that fueled the rise of what became Canada’s culturally dominant version of Ice Hockey in the 19th century.

In the true story of Ice Hockey history, Montreal is indeed the rock star of the 19th century. By the same analogy, however, Halifax must have been roadies par excellence. The spread of what people think of as “Montreal” ice hockey was very much a story of nationwide demand for Halifax gear. Our first two Stars handled that end of things from behind the scenes, until their own contributions to Ice Hockey’s rise became lost by that greatest form of flattery. Mass imitation.

In recent years, historical discussions have increasingly centered on what happened in Montreal two years after Halifax ice hockey was introduced there. We need to think in earlier terms, in order to address a host of fictions that have arisen from these various overly Montreal-centric treatments. Halifax’s legacy is awesome, frankly. It’s probably the greatest untold story of Canada’s 19th century. Our first two Stars’ backstories are not hard to understand. They are essential knowledge, for anyone who wants to really understand the story of Ice Hockey’s birth and earliest evolution. In the end, all theories and claims must answer what we know about Ice Hockey’s original part.

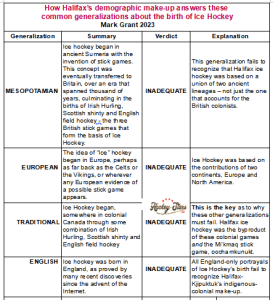

ADDRESSING CHATTER ABOUT EARLY ICE HOCKEY

In the current era, we have found that there’s much mixed messaging, regarding how Ice Hockey was born and how it evolved until the end of the 19th century. A few birther theories dominate this space and much of the chatter about how Ice Hockey came into existence.

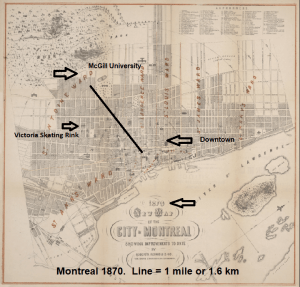

For decades, it’s become increasingly common to read or hear that Ice Hockey was somehow born in 1875 and that the first organized game was played then, in Montreal at the old Victoria Skating Rink (VSR). When it comes to what took place earlier, it’s been said for even longer that Ice Hockey evolved from three British stick games, each played on grass: Irish hurling, Scottish shinty and English grass hockey. More recently, since the introduction of the Internet, it has become common to say that Ice Hockey was born in England, most specifically, through grass hockey. These are some of the ideas that one is likely to find in era 2024, when doing a cursory search about the history of Ice Hockey.

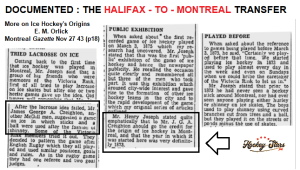

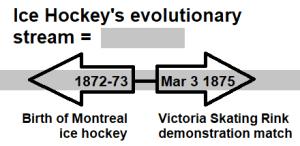

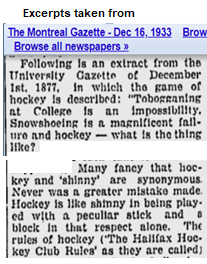

They are swiftly falsified by a newspaper article that’s gone lost to the public in general. I should add that hockey historians have known of this piece of primary evidence for eighty years now. Seen below, it’s an article from the November 27th 1943 edition of the Montreal Gazette newspaper. The article discusses the literal birth of Montreal ice hockey. Henry Joseph, an eyewitness and participant in the birth of ice hockey in Montreal tells us very clearly how and when ice hockey began in Montreal. The episode he describes took place in 1872 or 1873, two years before the VSR match of March 3, 1875. The key point is that the birth of Montreal ice hockey was based on the introduction of Halifax ice hockey. Forget everything you’ve been told about Ice Hockey being born two years later, in 1875.

This passage is of defining importance to real Ice Hockey history for two main reasons. First, it locks earlier (pre-Montreal) hockey history down to one very specific location, Halifax. Secondly, over the next two decades the Montrealers version of Ice Hockey evolved into the official version of Ice Hockey in Canada. Over the decades, hockey history discussions have increasingly focused on Montreal’s role to the exclusion of Halifax. This has caused the general public to lose sight of the fact that Montreal’s ice hockey was most fundamentally a Halifax-Montreal, Canadian-Mi’kmagi game, on multiple levels – not just technologically. As we shall see, the Halifax game’s unique hybrid “indigenous-colonial” makeup solves a number of unnecessary mysteries that circulate these days.

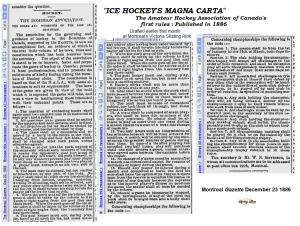

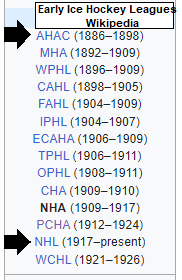

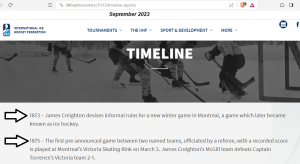

Montreal ice hockey began ascending in the national direction in the 1880s, and when the Montrealers created the first Ice Hockey League at the VSR in December of 1886. That was when the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada (AHAC) was founded. All modern Ice Hockey leagues are derived from the AHAC’s first rules, which were published in the Gazette a few weeks after they were written up at the VSR. The AHAC rules were adopted by the Stanley Cup trustees following the former’s introduction in 1892. The AHAC rules were transferred to a new organization in the 1890s, the Canadian Amateur Hockey League (CAHL).  The earliest professional leagues adopted these ever-evolving AHAC-CAHL charters, in a legacy of transference that includes the National Hockey League. So did the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) and Olympic ice hockey, in the early part of the 1900s. These are just some of the things that make Montreal so important to early Ice Hockey history.

The earliest professional leagues adopted these ever-evolving AHAC-CAHL charters, in a legacy of transference that includes the National Hockey League. So did the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) and Olympic ice hockey, in the early part of the 1900s. These are just some of the things that make Montreal so important to early Ice Hockey history.

The AHAC’s founding took place fourteen years after the 1872-73 birth of Montreal hockey. The most important point that Henry Joseph makes, because Montreal ice hockey turned out to be so important, is how he reminds us that Montreal hockey was literally based on a transfer from Halifax. It was transferred to Montreal by Halifax’s James Creighton. He’s the McGill man that Joseph mentions. Hockey historians know these things about Creighton for many, many reasons.

1 OF 3 HALIFAX’S LINEAL DISTINCTION : THE BIRTH OF HOCKEY IN MONTREAL

Henry Joseph told the Gazette that he and his chums had first tried playing lacrosse on skates, with “hectic” results. After that didn’t work out, he said that a McGill man, James Creighton, suggested that the group try another stick game, which Joseph very significantly likened to shinney. By then, around 1943, “shinney” had long since become a common way of referring to pond hockey in Canada. Joseph’s description provides an excellent general description of the activity involved, in other words —a game involving teams, sticks, goals, and a puck-like object. (So does Jeff Ward’s description of the first oochamunkukt game. Thomas Raddall’s most well-known mention of Halifax-Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw playing “hurley” is another common way of referring to pond “hockey.” These latter considerations remind us that “hockey” was not just a European game.)

Our eyewitness said that Montreal ice hockey was “definitely” born in 1873. However, a few years earlier, we seem to recall reading that Henry Joseph said that the same episode took place in 1872. That’s why, going forward, we say that Montreal ice hockey was born in the 1872–73 period.

Granted, Henry Joseph doesn’t say a lot about what took place when Montreal ice hockey was literally born. But what he does say allows us to infer things that likely or very likely took place and are of vital significance to our understanding of Ice Hockey history. Henry Joseph’s said that his crew only hacked the VSR on “some” Sundays. When all days of the week are treated equally, this means that there’s already a 6-in-7 (or 86 percent) likelihood that Montreal ice hockey was born outdoors. We think an outdoor birth is more likely in this case since the lacrosse experiment failed. Trying Creighton’s shinney-like game outdoors may have seemed the wiser choice to the founding fathers of Montreal hockey, Why risk inviting the ire of VSR management over another stick game that the group might also not like?

All signs point to the birth of Montreal occurring in this area, outside and very likely within walking distance of the VSR, downtown, and the McGill University campus:  Whether Montreal hockey was born indoors or outdoors is not what makes this episode definitively important to Ice Hockey history. There are other things that we can reasonably infer about what must have happened, soon after the Montrealers had all laced up and obtained their very first Mi’kmaq sticks. There would have come a time when the others deferred to James Creighton, to see what the group was supposed to do next. Creighton would have anticipated this moment. He had made himself the centre of attention following the failed lacrosse experiment. After that, he made everybody wait for the arrival of some Mi’kmaq sticks. How else could the Montrealers be expected to start playing a game that they’d never played before?

Whether Montreal hockey was born indoors or outdoors is not what makes this episode definitively important to Ice Hockey history. There are other things that we can reasonably infer about what must have happened, soon after the Montrealers had all laced up and obtained their very first Mi’kmaq sticks. There would have come a time when the others deferred to James Creighton, to see what the group was supposed to do next. Creighton would have anticipated this moment. He had made himself the centre of attention following the failed lacrosse experiment. After that, he made everybody wait for the arrival of some Mi’kmaq sticks. How else could the Montrealers be expected to start playing a game that they’d never played before?

The father of Montreal ice hockey may have only said a few words. He may have spoken at some length. Either way, there must have been some explanation on his part. What must have happened next was such a simple thing, but one with such far-reaching implications:

The Montrealers followed Creighton’s lead and began playing ice hockey for the very first time.

In that moment, Halifax, Nova Scotia attained immortal status in the true history of Ice Hockey. This is because of what Montreal ice hockey would become, especially over the next quarter-century. This is Halifax-Dartmouth-Kjipuktuk’s great lineal distinction. Only its game was transferred to Montreal, to the exclusion of all other games. This distinction stands regardless of how evolved or underdeveloped the Halifax game was. All that matters, in the lineal context, is that we can identify the particular “hockey” game that Montreal inherited.

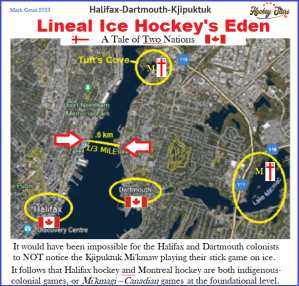

Know, then, that James Creighton cannot be the father of Ice Hockey. An entire mythology has been constructed around an attempt to make him out to be Ice Hockey’s Dad. Back in Halifax, he was just another dude who played hockey. Seriously, calling Creighton the father of Ice Hockey is not just bad history, it’s a diss to those partners who built the game that he inherited. There was already a stick market when he left for Montreal. This is where the birth of Montreal hockey points very directly, to the five-by-four mile area seen below. This is Ice Hockey’s Eden.

This is where James Creighton came from. We call this place Halifax. It may be more commonly known as the Halifax-Dartmouth area. In early hockey discussions, our featured area is more accurately described as Halifax-Dartmouth-Kjipuktuk, since the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw players lived at Tuft’s Cove and Lake Micmac.

This is the literal birthplace of “the” stick game that went on to become the official version of Ice Hockey, or what we call Ice Hockey and will sometimes call lineal “hockey.” Born in Halifax and transferred to Montreal, where it hit the big time. All versions of modern Ice Hockey can be traced to this location and a singular stick game.

The indigenous-colonial nature of our featured setting falsifies another much more settled theory about early Ice Hockey history. In that interpretation, Ice Hockey is said to have evolved from three British stick games, each played on grass: Irish hurling, Scottish shinty, and English field hockey. We called this the Traditional theory earlier. The Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw’s presence in Halifax hockey proves that Ice Hockey can’t possibly have evolved from three British stick games only. That’s the point. The enduring popularity of the British theory basically proves that Halifax has not been given careful consideration in historical hockey discussions. All suggestions that Ice Hockey evolved from only three British games there are like saying that the cardinal directions are North, South and West.

THE ESTABLISHMENT SPEAKS

It can be very helpful to know that hockey historians usually don’t mean that ice hockey was actually born in Montreal when they say such things. They will usually say that they mean born figuratively, if asked.

Likewise, no real historian will say that James Creighton is the literal father of Ice hockey or that the VSR hosted Ice Hockey’s first organized game in 1875. Not in any literal sense. Of course. The use of figurative descriptions is quite common in this space. The result is a matrix of quite meaningless statements, and the casual reader is left to sort out the code.

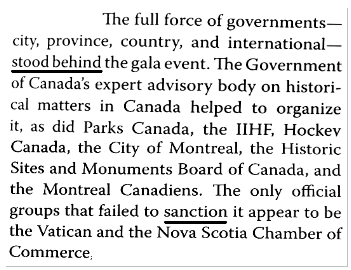

Decades in the making, this kind of figurative treatment attained semi-official status in 2008. That was when the governing body of Ice Hockey’s international game, the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF), called Montreal’s Victoria Skating Rink the birthplace of organized hockey and James Creighton, the father of organized Ice Hockey. This highly publicized event was part of the IIHF’s 100th anniversary celebration. And if Paul Henderson and Jim Prime are correct, in the first chapter of their 2011 book, How Hockey Explains Canada, the IIHF’s interpretations had the firm backing of various Canadian notables.

Here are the conclusions that all of these VIPs would supporting, if this reading is correct, from a couple of pages earlier.

This so-called show of support may have been oversold. There’s a big difference between supporting the general idea of enshrining Creighton and the VSR in general, and agreeing with the IIHF’s stated conclusions. It’s laudable that the IIHF did this, but the approach is also seriously misguided. More consequentially, it is misleading. James Creighton’s legacy is too diversified to be reduced to a single label like father.

Some members of the Society of International Hockey Research (SIHR) group tried to get Creighton into the Hockey Hall of Fame for at least ten years. And for very good reason. He was a great patriarch of the early game, and somewhat of a Moses-like figure in style and stature. He left Halifax for a new land, parting Ice Hockey’s 19th century with a special skate and stick. Once resettled in his new land, Montreal, he gathered a new people. Near the foot of Mount Royal, he made them descendants of his former tribe. Creighton’s commandments were published nearby a few years earlier, in 1877, and transferred to the AHAC where they became a legislative pillar of modern Ice Hockey. Creighton, the literal father of Montreal ice hockey, was also a promoter and entrepreneur of far-reaching consequence. In our opinion, his greatest contribution to Ice Hockey has gone completely unconsidered: it is what he represented as an archetypal evolutionary figure that should explain Montreal ice hockey’s 19th-century conquest of Canada.

* ICE HOCKEY’S mid-20th CENTURY ‘CIVIC’ DEBATE

How did we get to this point, where Halifax is not even mentioned in descriptions of Ice Hockey’s birth? Despite what we know? I don’t know, but I can say a bit about how the national discussion on Ice Hockey history took off in the mid-20th century.

By the early 1940s, Ice Hockey had become Canada’s favourite pastime. Fans listened to NHL games from coast to coast. They went to movie theatres to watch the highlights. Around this time, there was some chatter about building a Hockey Hall of Fame, and placing the future Hall in the community where Ice Hockey was born. Three civic birthplace contenders emerged: Kingston, Halifax, and Montreal.

In the end, the birthplace debate didn’t matter. The Hall wound up going to downtown Toronto in 1961, but only after the Hall’s executives had endorsed Kingston. The Kingston was later falsified. With that, only Halifax and Montreal remained in Ice Hockey’s birthplace debate. Ice Hockey’s birthplace discussion receded to the background, during a lengthy pre-Internet era when it was much more difficult to share and properly vet evidence.

At some point, it would appear that the Montreal theories began taking over. For unknown reasons, the Victoria Skating Rink’s March 3, 1875 match gained disproportionate favour, virtually eclipsing all that took place in Montreal ice hockey before 1875. Now there is a serious imbalance between what we are told about the early game and what actually occurred. Fortunately, the remedy is simple. All current descriptions of Montreal ice hockey’s significance should be reviewed in relation to what we know about Halifax hockey, as Halifax hockey was before the 1873-73 Halifax-to-Montreal transfer.

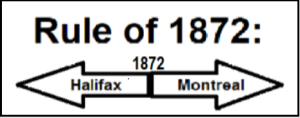

* 19th CENTURY ICE HOCKEY’S ‘RULE OF 1872’

The rule of 1872 divides the 19th century into two parts, as far as Ice Hockey is concerned.

1 of 2 -There is that which happened in or in relation to Halifax ice hockey until James Creighton moved to Montreal, in 1872;

2 of 2 – And, there is that which took place in Montreal after the birth of Montreal ice hockey.

And so Ice Hockey’s Rule of 1872 goes as follows:

In order for a community, game or innovation to rightfully earn a place in the true story of early Ice Hockey, one must show how an item (a) merged with Halifax ice hockey prior to James Creighton’s departure in ca. 1872, or (b) how it merged with Montreal ice hockey after 1872.

The earliest such reference is the best measure of an item’s introduction into Ice Hockey’s evolutionary stream. After 1872, an item must merge with Montreal ice hockey. Even Halifax isn’t immune to this rule. For example, the suggestion that Ice Hockey’s first goalie nets came from Nova Scotia or Ontario relies solely on the fact that Montreal ice hockey adopted them. We acknowledge that 1873 may prove to be the better year, but we will stay with 1872 here for consistency’s sake.

* SUBTOPIC: THE “FIRST WOODEN PUCK”

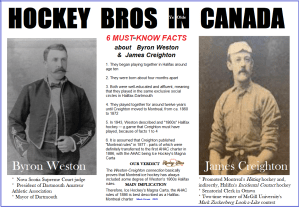

It’s often said that Ice Hockey’s first wooden puck was introduced at the VSR on March 3, 1875. Since this is the earliest evidence of the wooden puck in Montreal that we know of, our next move is to consider pre-1872 Halifax, by following the Rule of 1872. Is any earlier evidence of the wooden puck there?  Indeed, there is. Hockey historians have known for at least eighty years now that blocks of wood were sometimes used in Halifax ice hockey as early as the 1860s. Moreover, they know this from another must-know person in the story of early Ice Hockey, a Nova Scotia Supreme Court judge named Bryon Weston.

Indeed, there is. Hockey historians have known for at least eighty years now that blocks of wood were sometimes used in Halifax ice hockey as early as the 1860s. Moreover, they know this from another must-know person in the story of early Ice Hockey, a Nova Scotia Supreme Court judge named Bryon Weston.

So, forget about Montrealers introducing the wooden puck in 1875. It’s just another VSR birther mythology.

However, we still must go further. Two steps are involved when we consider pre-Montreal Halifax hockey. We must also look to the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw, who lived here alongside the Halifax-Dartmouth colonists. We discussed the puck topic in the first essay, actually, and found evidence to suggest that the Mi’kmaq First Nation may have been using wooden pucks before the Halifax-Dartmouth colonists’ arrival in 1749.

This is a good example of how the Rule of 1872 can work, for those who are interested. People have been ignoring Halifax for far too long, and overlooking the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw as well the colonists who lived there.

Left unchecked, myths have a way of building on themselves. And so it’s often been said that the rubber puck soon followed the wooden puck’s 1875 debut at the VSR. Some say the rubber puck was introduced in Montreal. Others say Kingston. Sometime in the 1880s. None of this matters.

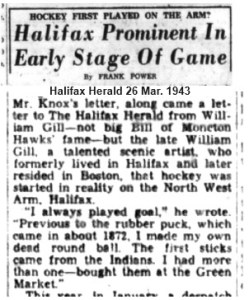

In 1943, William Gill, a contemporary of Creighton and a painter of some reputation, was quoted in the Halifax Herald as saying that the rubber puck had been introduced in Halifax “about 1872.”

Montreal can lay claim to the rubber puck’s first legislated appearance, in the 1886 AHAC charter, and the first time that the modern puck’s dimensions were mentioned in written form: 3 by 1 inches exactly. In the most recent split-image, one saw a Mi’kmaq wooden puck of these exact dimensions. We don’t believe that the Mi’kmaw introduced the 3″ x 1″ puck, personally. It’s too precise of a British imperial proportion. That said, the Mi’kmaw may have used wooden pucks that were about that size, which inspired the 3″ x 1″ puck.

Bottom line: The Rule of 1872 has taken us a long way from the fairytale about the wooden puck.” The lesson here bears repeating: If one’s goal is to learn the true lineal history of Ice Hockey, as that applies to the 19th century in general, Montreal and Halifax must be considered together as a rule.

The Rule of 1872 reminds us that the VSR match of 1875 and the birth of Montreal are equally important to our understanding of the evolution of early Ice Hockey, but for different reasons. The VSR match reminds us of what happened later in Ice Hockey’s evolutionary stream. The birth of Montreal points to what happened earlier.

* WINDSOR

Earlier, we suggested that Canadians first began asking where Ice Hockey was born in the mid-1900s. Of the three civic contenders that emerged, Kingston dropped out of the running at some point. The documented birth of Montreal ice hockey leaves only one contender. By default, it would appear that Halifax must be the literal birthplace of “the stick game that became Ice Hockey.”

Not so fast. Just before the turn of the millennium, a new theory appeared in which Windsor, Nova Scotia, was said to be the literal birthplace of Ice Hockey.

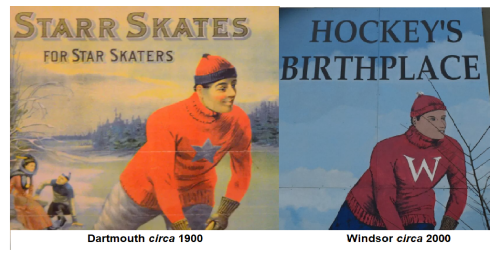

Once again, there were two civic contenders.  The Windsor theory was introduced by the late Dr. Garth Vaughan in the 1990s. Since then, it has enjoyed the backing of local politicians, local artists and even the Department of Transportation. These things, combined with the city’s ongoing promotional efforts, have made Windsor one of the mainstream media’s go-to sources when it comes to the birth of what many call Canada’s Game.

The Windsor theory was introduced by the late Dr. Garth Vaughan in the 1990s. Since then, it has enjoyed the backing of local politicians, local artists and even the Department of Transportation. These things, combined with the city’s ongoing promotional efforts, have made Windsor one of the mainstream media’s go-to sources when it comes to the birth of what many call Canada’s Game.

And why shouldn’t the media be interested, since Dr. Vaughn claimed that the matter has been “proved” in the title of an essay that continues to appear at birthplaceofhockey.com, the Windsor theorists’ online home:

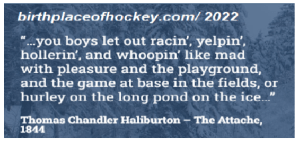

To our understanding, the basis of the Windsor claim is very straightforward. It’s based on a passage in a book that was published in 1844, The Attache, by Thomas Haliburton. The well-known Haliburton was born in Windsor on December 17, 1796. This is said to be the central piece of evidence that Vaughn and birthplaceofhockey.com continue to cite as “proof” that Ice Hockey’s was born in Windsor.

The website is overseen by a twelve-member Windsor Heritage Society. As a group, the Windsor society supports Dr. Vaughn’s claim on one of the subpages, and seems to consider the matter of Ice Hockey’s birth settled:

Here is the ‘key’ passage, where Haliburton reminisces on his school days at Windsor’s King’s College which he attended around 1805 to 1810.

Here is the ‘key’ passage, where Haliburton reminisces on his school days at Windsor’s King’s College which he attended around 1805 to 1810.  As we noted through the Rule of 1872, it is one thing to claim to be Ice Hockey’s literal birthplace. Windsor supporters must also show how the Windsor game was transferred to Halifax before Creighton moved to Montreal. Vaughn understood this, and answered the transfer question this way.

As we noted through the Rule of 1872, it is one thing to claim to be Ice Hockey’s literal birthplace. Windsor supporters must also show how the Windsor game was transferred to Halifax before Creighton moved to Montreal. Vaughn understood this, and answered the transfer question this way.

Given Vaughn’s wording, I should point out that we seem to have no journal entries or reports that attest to such a specific Fort Edwards-to-Halifax transfer. If such information is available, it would be helpful if it were posted near Vaughn’s essay. So, why Fort Edwards, then? Suppose there were twenty-five military settlements in colonial Canada when King’s College opened, aside from the one in Halifax. Why should we rule out the other twenty-four settlements in Fort Edwards’ favour? This is exactly what Henry Joseph’s testimony allows us to do in the case of the real-life Halifax-to-Montreal transfer.

Since Dr. Vaughn is no longer able to explain his thinking, we must hazard a guess. If Ice Hockey was literally born on King’s College’s Long Pond, Fort Edwards becomes the most logical choice for being the closest military settlement to King’s College. It’s important to know that the Windsor theory was developed before we became aware that people beyond Canada also played ‘stick games on ice’ during the pre-1872 era. This was a major revelation, but only to the extent that it falsified the notion that ‘stick games on ice’ first appeared in colonial Canada.

Ironically, all of these new findings are beside the point in the lineal-evolutionary sense. That’s because only one stick game was transferred to Montreal in 1872–73, to the exclusion of all other stick games that were played at that time. It doesn’t matter that Windsor ice hockey was “embryonic” at the time of its birth. All that matters is that such a single game was transferred to Halifax and then Montreal.

Windsor supporters are saying ‘the stick game that became Ice Hockey’ was literally born in Windsor. It began with hurley only, to the exclusion of all other stick games. There it evolved for some time, as games usually do, before being transferred to Halifax. After evolving further in Halifax, this now-hybrid Windsor-Halifax stick game was transferred to Montreal. There it evolved further, now as a Windsor-Halifax-Montreal game, until it claimed the title of Ice Hockey by public acclimation in Canada prior to the end of the 19th century.

All of this adds to the Haliburton passage’s central importance in the Windsor way of thinking. It would appear that the Fort Edwards-to-Halifax transfer claim relies entirely on the Haliburton birth claim.

But the Haliburton passage must not be considered in isolation. While it’s true that those newly discovered stick games have no bearing on Windsor’s lineal claim, they tell us in no uncertain terms that Canada’s colonists lived during a time when people played stick games on ice on both sides of the Atlantic. In Windsor’s way of thinking, Halifax must be an exception.

The colonists in Halifax must have never played stick ball on ice once. Had they done so, that would mean they played “hockey” before the arrival of the enlightened Fort Edwards soldiers The era here is 40 winters, 1749 to 1788, when King’s College opened in Windsor. We also know that Halifax was a kind of central area that British soldiers passed through with regularity.

We emphasize that this is only our understanding of the Windsor birthplace claim. We may be missing something big here, like evidence that actually proves their two central claims (of birth and transfer). Of course, it’s possible that the current Windsor supporters’ use of “proof” is meant to be understood in some sort of mysterious figurative context. That would hardly be unprecedented in this space. On that note, let’s consider one of the VSR birther mythology’s most misleading figurative daisies.

2 OF 3 HALIFAX’S LEGISLATED DISTINCTION THE VSR “FIRST ORGANIZED GAME” MYTH

People have been saying that “organized” ice hockey was first introduced in Montreal at the Victoria Skating Rink in 1875, long before the IIHF’s centennial celebration in 2008. Various elements from the March 3, 1875 match are cited as proof of “organization.” We would certainly agree that those things represent evidence of organization. But they are certainly not the “first” evidence of organized Ice Hockey.

In 2006, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) did a very nice job of summarizing this settled depiction near the start of their TV series Hockey: A People’s History (and by “CBC,” we refer to the editorial team that oversaw this production). Early on, one sees some colonists playing a stick game on ice with various kinds of sticks. The setting appears to be somewhere in Nova Scotia, perhaps Halifax-Dartmouth. As we watch their “scrum-like” game unfold, the CBC’s narrator declares that ice hockey was a “wild, chaotic affair” with few rules in the mid-1800s.

This downgrading of ‘all things previous’ is often meant to invite the conclusion that Montreal introduced “organized” Ice Hockey. And why should anyone doubt the confident narrator, given the involvement of the cerebral CBC? The better question asks this: How much can the CBC actually know about Ice Hockey’s pre-Montreal era?

When we look past the stereotyping, the resoundingly correct answer must be, Not very much at all. In On the Origins of Hockey (2014), Carl Giden, Patrick Houda, and Jean-Patrice Martel cite a total of 23 Canadian colonial references to what is or may be ice hockey prior to the Halifax-to-Montreal transfer of 1872–73. If this is about right, then the CBC is relying on 23 mostly very vague descriptions in order to generalize about an era that could have lasted up to 123 years (from 1749 to 1872) prior to the birth of Montreal ice hockey. That’s one vague passage every five years or so.

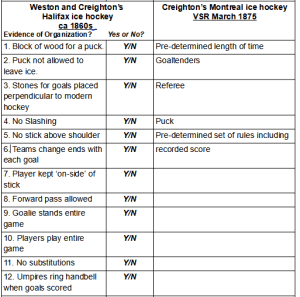

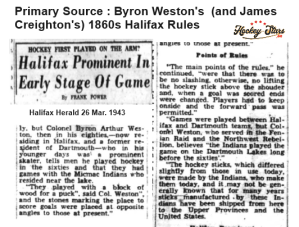

* WESTON AND CREIGHTON’s 1860s HALIFAX ICE HOCKEY The more concerning thing is that Canada’s main social media influencer failed to mention something that hockey historians had known for more than sixty years prior to the debut of Hockey: A People’s History. The CBC has failed to mention the 1943 testimony of that Nova Scotia Supreme Court judge we mentioned earlier, Byron Weston. In this essay, we mention the article where Weston’s summary of Halifax ice hockey is mentioned a few times, because it’s that important to early Ice Hockey. The entire article can be found here. Despite it’s great importance to real Ice Hockey history, the one thing the relevant passage doesn’t divulge is why Byron Weston’s Halifax rules simply must be mentioned in any serious discussion of Montreal ice hockey’s evolution, rather than ignored: It is because we know that Byron Weston grew up with the father of Montreal ice hockey, literally. Some of the essential facts are as follows: James Creighton was born in Halifax on June 12, 1850. Weston moved to Halifax at  the age of ten, around 1860. The two were separated in age by only four months. Both were known athletes, and they may have played together for up to twelve years before Creighton moved to Montreal. Both would go on to law school. In the 1860s, Halifax-Dartmouth had about 35,000 people, and there was much illiteracy. Only ten percent of the population belonged to Weston’s and Creighton’s upper class. In such a tight environment, it would have been impossible for Weston and Creighton to not know each other. In such a tight environment, it would have been impossible for Weston and Creighton to not know each other. The main consequence of this observation is very important: Byron Weston’s 1860s Halifax ice hockey rules must describe a very particular ‘stick game’ that James Creighton – the father of Montreal ice hockey – knew very well growing up. We don’t need to accept on faith that organized hockey was born in 1875 at the Victoria Skating Rink. The aforementioned “Rule of 1872” asks which community can show the earliest evidence of organized hockey, Halifax or Montreal? The answer is clearly Halifax because we know that James Creighton must have transferred Byron Weston’s game to some degree. To assume otherwise is very counter-intuitive, given their known relationship! On the left side of the table below, one sees Byron Weston’s description of 1860s Halifax ice hockey. On the right are some of the reasons why the March 3, 1875, match is supposed to be Ice Hockey’s first organized game. The only way the later VSR match can hope to be Ice Hockey’s first organized game, is if all of Weston’s earlier Halifax’s rules do not reflect organization. Otherwise, Weston’s Halifax ice hockey must have been “organized” to some degree.

the age of ten, around 1860. The two were separated in age by only four months. Both were known athletes, and they may have played together for up to twelve years before Creighton moved to Montreal. Both would go on to law school. In the 1860s, Halifax-Dartmouth had about 35,000 people, and there was much illiteracy. Only ten percent of the population belonged to Weston’s and Creighton’s upper class. In such a tight environment, it would have been impossible for Weston and Creighton to not know each other. In such a tight environment, it would have been impossible for Weston and Creighton to not know each other. The main consequence of this observation is very important: Byron Weston’s 1860s Halifax ice hockey rules must describe a very particular ‘stick game’ that James Creighton – the father of Montreal ice hockey – knew very well growing up. We don’t need to accept on faith that organized hockey was born in 1875 at the Victoria Skating Rink. The aforementioned “Rule of 1872” asks which community can show the earliest evidence of organized hockey, Halifax or Montreal? The answer is clearly Halifax because we know that James Creighton must have transferred Byron Weston’s game to some degree. To assume otherwise is very counter-intuitive, given their known relationship! On the left side of the table below, one sees Byron Weston’s description of 1860s Halifax ice hockey. On the right are some of the reasons why the March 3, 1875, match is supposed to be Ice Hockey’s first organized game. The only way the later VSR match can hope to be Ice Hockey’s first organized game, is if all of Weston’s earlier Halifax’s rules do not reflect organization. Otherwise, Weston’s Halifax ice hockey must have been “organized” to some degree.  Circle ‘N’ each time you think a Halifax rule does not reflect some form of organization. Answer ‘N’ to all of the items, and the March 3, 1875 VSR match may be the first instance of organized hockey. Circle ‘Y’ once, and that distinction goes to Halifax. Another popular myth wilts in the presence of Halifax. * THE VSR “NEW” GAME MYTH In recent decades it has become increasingly vogue to say that James Creighton devised a “new” game in Montreal. In most cases, this use of new is figurative in nature, and often rooted in the fact that Henry Joseph said Montreal ice hockey was fashioned after English rugby and English field hockey, soon after the Halifax transfer of 1872-73. Let’s start with the most important item of the two just mentioned: Montreal’s incorporation of rugby was a highly significant development in ice hockey’s evolution. However, rugby’s incorporation doesn’t change the fact that Montreal ice hockey remained an adaptation of the Halifax game. It’s also true that English field hockey was written into Montreal’s 1877 rules. Seen below, we know that a good portion of the 1877 rules were basically copied from an English field hockey source. Those “English” rules can be found in items 1, 4, 5, and 6. They account for about three-quarters of the 1877 text. At a glance then, it may seem reasonable to conclude that the famous Montreal Rules were’mainly’ about English field hockey.

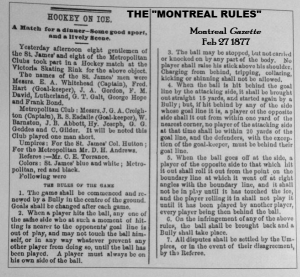

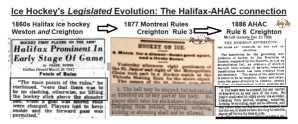

Circle ‘N’ each time you think a Halifax rule does not reflect some form of organization. Answer ‘N’ to all of the items, and the March 3, 1875 VSR match may be the first instance of organized hockey. Circle ‘Y’ once, and that distinction goes to Halifax. Another popular myth wilts in the presence of Halifax. * THE VSR “NEW” GAME MYTH In recent decades it has become increasingly vogue to say that James Creighton devised a “new” game in Montreal. In most cases, this use of new is figurative in nature, and often rooted in the fact that Henry Joseph said Montreal ice hockey was fashioned after English rugby and English field hockey, soon after the Halifax transfer of 1872-73. Let’s start with the most important item of the two just mentioned: Montreal’s incorporation of rugby was a highly significant development in ice hockey’s evolution. However, rugby’s incorporation doesn’t change the fact that Montreal ice hockey remained an adaptation of the Halifax game. It’s also true that English field hockey was written into Montreal’s 1877 rules. Seen below, we know that a good portion of the 1877 rules were basically copied from an English field hockey source. Those “English” rules can be found in items 1, 4, 5, and 6. They account for about three-quarters of the 1877 text. At a glance then, it may seem reasonable to conclude that the famous Montreal Rules were’mainly’ about English field hockey.  Don’t be misled by the number of “English” letters in the Montreal law. The vast majority of the English field hockey text pertains to face-offs (rules 4-6). As every hockey player knows, face-offs are only a small part of any hockey game. Henry Joseph’s likening of Creighton’s Halifax game to “shinney” reminds us that Montreal inherited a game that involved teams, sticks, goals, and a ball or puck-like object. His testimony in this regard corrects all suggestions that Montrealers created a new game from field hockey, as if those elements weren’t already present: Halifax ice hockey was already like English field hockey before Creighton introduced it to Montreal, just as it was also already like Irish hurling, Scottish shinty, and the Mi’kmaq game, which we understand was called oochamkunukt. * HALIFAX’S ‘LEGISLATED‘ PLACE IN MODERN ICE HOCKEY The part of the original article where Byron Weston’s Halifax Rules first appeared is seen below. A word of caution: the lists of Weston’s rules found online are usually a little different. For one thing, most have Weston saying that Halifax ice hockey was played with two 30-minute halves and a 10-minute break. We found no mention of that in the primary article.

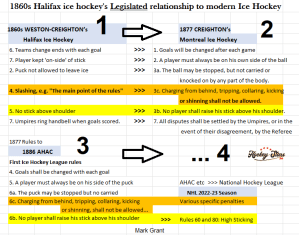

Don’t be misled by the number of “English” letters in the Montreal law. The vast majority of the English field hockey text pertains to face-offs (rules 4-6). As every hockey player knows, face-offs are only a small part of any hockey game. Henry Joseph’s likening of Creighton’s Halifax game to “shinney” reminds us that Montreal inherited a game that involved teams, sticks, goals, and a ball or puck-like object. His testimony in this regard corrects all suggestions that Montrealers created a new game from field hockey, as if those elements weren’t already present: Halifax ice hockey was already like English field hockey before Creighton introduced it to Montreal, just as it was also already like Irish hurling, Scottish shinty, and the Mi’kmaq game, which we understand was called oochamkunukt. * HALIFAX’S ‘LEGISLATED‘ PLACE IN MODERN ICE HOCKEY The part of the original article where Byron Weston’s Halifax Rules first appeared is seen below. A word of caution: the lists of Weston’s rules found online are usually a little different. For one thing, most have Weston saying that Halifax ice hockey was played with two 30-minute halves and a 10-minute break. We found no mention of that in the primary article.  Through the rule of evolution, all modern Ice Hockey leagues and organizations will be retraceable beyond Montreal, at least as far as Byron Weston’s and James Creighton’s 1860s Halifax ice hockey. Elements of the Halifax game were transferred to Montreal, and written up in the Montreal Rules of 1877. Then those same rules were transferred to the first AHAC rules in 1886: the terminal point of all modern Ice Hockey leagues and organizations. The more common way that Halifax merged with modern Ice Hockey is depicted by the orange lines in the graph below.

Through the rule of evolution, all modern Ice Hockey leagues and organizations will be retraceable beyond Montreal, at least as far as Byron Weston’s and James Creighton’s 1860s Halifax ice hockey. Elements of the Halifax game were transferred to Montreal, and written up in the Montreal Rules of 1877. Then those same rules were transferred to the first AHAC rules in 1886: the terminal point of all modern Ice Hockey leagues and organizations. The more common way that Halifax merged with modern Ice Hockey is depicted by the orange lines in the graph below.  James Creighton restated Weston’s main point about gentlemanly play in greater detail in the 1877 Montreal Charter (Box 2). He mentioned five infractions, instead of just one, in elaborating on the general idea of gentlemanly play in Rule 3c: “charging from behind, tripping, collaring, kicking, or shinning shall not be allowed.” Slashing wouldn’t have been allowed in Montreal ice hockey either. Creighton didn’t mention that infraction because slashing would have been understood to be a violation of the main point that Montreal’s Rule 3c conveyed in general. Halifax’s rule against slashing was upheld this way in Montreal, implicitly. It’s an obvious yet crucial historical point, for being one of the ways which show the AHAC rules were a Halifax-Montreal piece of legislation, rather than being a charter concocted by Montrealers completely from scratch. Creighton’s 1877 Rule 3c was then transferred, verbatim, to the AHAC via Rule 6 in the 1886 charter.

James Creighton restated Weston’s main point about gentlemanly play in greater detail in the 1877 Montreal Charter (Box 2). He mentioned five infractions, instead of just one, in elaborating on the general idea of gentlemanly play in Rule 3c: “charging from behind, tripping, collaring, kicking, or shinning shall not be allowed.” Slashing wouldn’t have been allowed in Montreal ice hockey either. Creighton didn’t mention that infraction because slashing would have been understood to be a violation of the main point that Montreal’s Rule 3c conveyed in general. Halifax’s rule against slashing was upheld this way in Montreal, implicitly. It’s an obvious yet crucial historical point, for being one of the ways which show the AHAC rules were a Halifax-Montreal piece of legislation, rather than being a charter concocted by Montrealers completely from scratch. Creighton’s 1877 Rule 3c was then transferred, verbatim, to the AHAC via Rule 6 in the 1886 charter.  As noted, the AHAC’s Halifax-Montreal rules were transferred to the CAHL in the mid-1890s. Suffice it to say that later leagues began to elaborate on what was meant by the AHAC’s original Rule 6. As this occurred, the CAHL rules on “ungentlemanly” play became more detailed. The NHL’s rules on cross-checking, spearing, and boarding are examples of such elaborations and examples of a transfer process that applies to all modern ice hockey leagues and organizations, since they all funnel back to the singular stick game that was AHAC hockey. The yellow line in the preceding diagram shows how this transference process plays out in a more specific way. The NHL’s 2022–23 rules on high-sticking (60 and 80) can be traced back to the AHAC’s founding and all the way to the Halifax ponds, where raising the stick above one’s shoulder was expressly prohibited. Next time you see a high-sticking penalty called anywhere, think of those 1860s Halifax hockeyists, Byron Weston and James Creighton. The lesson here is as far-reaching as it is straight-forward. Many of modern ice hockey’s most common penalties can be traced back beyond the AHAC’s founding to 1860s Halifax. The Rule of 1872 is clear: the March 3, VSR match of 1875 did not mark the introduction of “organized” Ice Hockey either. Its historical significance must be reconsidered and reframed, with Halifax’s organized game in mind. All of the Montreal-centric figurative descriptions need to be considered, as we were saying, especially during an era when institutions like the IIHF write Halifax, Nova Scotia, out of the sport’s earliest history completely.

As noted, the AHAC’s Halifax-Montreal rules were transferred to the CAHL in the mid-1890s. Suffice it to say that later leagues began to elaborate on what was meant by the AHAC’s original Rule 6. As this occurred, the CAHL rules on “ungentlemanly” play became more detailed. The NHL’s rules on cross-checking, spearing, and boarding are examples of such elaborations and examples of a transfer process that applies to all modern ice hockey leagues and organizations, since they all funnel back to the singular stick game that was AHAC hockey. The yellow line in the preceding diagram shows how this transference process plays out in a more specific way. The NHL’s 2022–23 rules on high-sticking (60 and 80) can be traced back to the AHAC’s founding and all the way to the Halifax ponds, where raising the stick above one’s shoulder was expressly prohibited. Next time you see a high-sticking penalty called anywhere, think of those 1860s Halifax hockeyists, Byron Weston and James Creighton. The lesson here is as far-reaching as it is straight-forward. Many of modern ice hockey’s most common penalties can be traced back beyond the AHAC’s founding to 1860s Halifax. The Rule of 1872 is clear: the March 3, VSR match of 1875 did not mark the introduction of “organized” Ice Hockey either. Its historical significance must be reconsidered and reframed, with Halifax’s organized game in mind. All of the Montreal-centric figurative descriptions need to be considered, as we were saying, especially during an era when institutions like the IIHF write Halifax, Nova Scotia, out of the sport’s earliest history completely.  ANCIENT GAMES Earlier, we mentioned the CBC’s Hockey: A People’s History. In that TV series, the narrator said that Ice Hockey was born under the hot sands of Egypt, Persia, and Greece, as the viewer focuses on the nearby image of a 2,500-year-old carving from the Parthenon in Greece.

ANCIENT GAMES Earlier, we mentioned the CBC’s Hockey: A People’s History. In that TV series, the narrator said that Ice Hockey was born under the hot sands of Egypt, Persia, and Greece, as the viewer focuses on the nearby image of a 2,500-year-old carving from the Parthenon in Greece.  The CBC likely mentioned “Egypt, Persia, and Greece” because of colonial Canada’s connection to Britain and France. If so, they are basically equating the long march of Mesopotamian-Western civilization with Ice Hockey’s evolution. That’s a problem, and not just because that story really begins in Sumeria. It’s that two ancient human lineages were involved in the case of ‘the stick game that became Ice Hockey’. Halifax-Dartmouth-Kjipuktuk hockey was the byproduct of two parent continents. The CBC’s sweeping creation story only alludes to the European one. This occurs with every suggestion that early Ice Hockey was born in Europe through Celts, Vikings, and/or Dutch ice-golf players from the 1500s—whatever the latest European evidence may suggest. All such suggestions remain inadequate, unless the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw are mentioned as co-creators in the same presentation. The theories just mentioned all borrow from what we called the “Traditional” theory of Ice Hockey’s birth in our first essay—the theory that it emerged from some combination of Irish hurling, Scottish shinty, and English grass hockey. The indigenous-colonial reality of pre-Montreal Halifax hockey tells us that such colonial-only thinking doesn’t go far enough at every level. We must amend the British theory, for the same reason that one shouldn’t ask for a table for three when entering a diner as a party of four. The Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw’s involvement in the Halifax-to-Montreal transfer has devastating effects for the Traditional theory and all claims that borrow from it, including the now-vogue suggestion that Ice Hockey was born in England.

The CBC likely mentioned “Egypt, Persia, and Greece” because of colonial Canada’s connection to Britain and France. If so, they are basically equating the long march of Mesopotamian-Western civilization with Ice Hockey’s evolution. That’s a problem, and not just because that story really begins in Sumeria. It’s that two ancient human lineages were involved in the case of ‘the stick game that became Ice Hockey’. Halifax-Dartmouth-Kjipuktuk hockey was the byproduct of two parent continents. The CBC’s sweeping creation story only alludes to the European one. This occurs with every suggestion that early Ice Hockey was born in Europe through Celts, Vikings, and/or Dutch ice-golf players from the 1500s—whatever the latest European evidence may suggest. All such suggestions remain inadequate, unless the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw are mentioned as co-creators in the same presentation. The theories just mentioned all borrow from what we called the “Traditional” theory of Ice Hockey’s birth in our first essay—the theory that it emerged from some combination of Irish hurling, Scottish shinty, and English grass hockey. The indigenous-colonial reality of pre-Montreal Halifax hockey tells us that such colonial-only thinking doesn’t go far enough at every level. We must amend the British theory, for the same reason that one shouldn’t ask for a table for three when entering a diner as a party of four. The Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw’s involvement in the Halifax-to-Montreal transfer has devastating effects for the Traditional theory and all claims that borrow from it, including the now-vogue suggestion that Ice Hockey was born in England.  Finally, we note that the CBC narrator’s later mention of the Mi’kmaw as craftsmen is also in keeping with the settled British invention theory. It’s very well known that the Halifax-Dartmouth colonists hired the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw to make their hockey sticks. Curiously, there’s no evidence of the Mi’kmaw also making hurleys, caymans, and grass hockey sticks. Why only hockey sticks? Did the Halifax-Dartmouth colonists hire other First Nation groups to make those sticks? Or, maybe the Halifax colonists recognized the superior utility of oochamkunukt sticks on ice, which the Mi’kmaw storyteller Jeff Ward says were like today’s “hockey sticks.” In our first essay, we argued that Ward can only be alluding to the hockey stick’s end, which is defined by its flat thin blade. If such sticks were available in Kjipuktuk when the Halifax and Dartmouth colonists arrived in 1749–50, there would have been no need for those colonists to evolve British sticks into hockey sticks in Halifax–Dartmouth. We should expect this to be the general rule in other communities, however.

Finally, we note that the CBC narrator’s later mention of the Mi’kmaw as craftsmen is also in keeping with the settled British invention theory. It’s very well known that the Halifax-Dartmouth colonists hired the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw to make their hockey sticks. Curiously, there’s no evidence of the Mi’kmaw also making hurleys, caymans, and grass hockey sticks. Why only hockey sticks? Did the Halifax-Dartmouth colonists hire other First Nation groups to make those sticks? Or, maybe the Halifax colonists recognized the superior utility of oochamkunukt sticks on ice, which the Mi’kmaw storyteller Jeff Ward says were like today’s “hockey sticks.” In our first essay, we argued that Ward can only be alluding to the hockey stick’s end, which is defined by its flat thin blade. If such sticks were available in Kjipuktuk when the Halifax and Dartmouth colonists arrived in 1749–50, there would have been no need for those colonists to evolve British sticks into hockey sticks in Halifax–Dartmouth. We should expect this to be the general rule in other communities, however.

SUMMARY

In today’s world, it has become necessary to address a number of popular ideas that distort rather than inform our understanding of Ice Hockey history. The 1872-73 birth of Montreal ice hockey is superbly useful in this respect. It cuts through a load of crap by proving that Montreal transferred an indigenous-colonial game from Halifax, to the exclusion of all other communities. With no other cities making such an earlier claim, it is up to Windsor to show how its game was transferred to Halifax prior to the birth of Montreal ice hockey in 1872-83.

Until this is shown, logic dictates that Halifax ice hockey must have born withing Halifax because there is no credible transfer claim to suggest otherwise. The solution of Ice Hockey’s literal birth is straightforward. The stick game that became Ice Hockey (after the Halifax-Montreal transfer) could not have been born until players from two continents met up, following the founding of Halifax on June 21, 1749. It’s that simple, since this indigenous-colonial hybrid game had to wait for the arrival of the colonists.

All versions of modern hockey can be traced to a single stick game that could not have been born any earlier than the winter of 1749-50, literally:

In our first essay, we suggested that this First Meeting on ice took place sooner rather than later. That is, there’s a tendency to not think beyond the earliest hard evidence of hockey which in the Canadian arena dates no earlier than the 1800s. Common sense requires one to read between the lines and think seriously about the winter of 1749–50. After all, it would have been impossible for the first Halifax and Dartmouth colonists to not notice the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw playing oochamkunukt in this very tight area.

Halifax-Dartmouth-Kjipuktuk

I finished my Mi’kmaq Hall of Fame nomination essay in December 2021. A couple of years later, while writing about Halifax, I found a letter that I’d never heard of during my earlier investigations of Ice Hockey. It was written in 1954 by the historian, Thomas Raddall. In the letter, Raddall tells a dentist that the discovery of the Mi’kmaw did involve the “first” settlers and that he found “several” references to the Mi’kmaq stick game while researching his famous 1948 book, Halifax: Warden of the North.

The 1954 letter is of great fundamental importance for a few reasons. First, it seems to have gone overlooked. I’d never heard of it before. His commentary brings us one step closer to actual proof that the Mi’kmaw did play a hockey-like game – as they claim – prior to the colonists’ arrival. Secondly, our Order of Canada historian hints at the possibility that we may find such direct references to the Mi’kmaq game by following his footnotes. Here’s a link to Raddall’s letter, to which I have added a couple of other essential comments from Nova Scotia sources regarding the Mi’kmaw’s involvement in “Halifax” hockey.

Raddall supports the only birthing claim of Halifax hockey that makes sense, as it clearly must when pre-Montreal Halifax’s demography is given the slightest consideration. Basically, he and others say that the Halifax-Dartmouth colonists met up with the local Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw with whom they began playing a version of hockey.

We aren’t done discussing Halifax’s contributions to Canada’s favourite game. However, at this point, we can pause to show four ways that this Halifax-Montreal paradigm resolves some unnecessary mysteries about the true story of Ice Hockey’s birth and earliest evolution.

1 of 4. We can identify when Ice Hockey’s literal birth took place, to an extent that has gone largely unconsidered.

The birth of ‘the stick game that became Ice Hockey’ must have taken place no earlier than the winter of 1749-50. We can say this with certainty because James Creighton transferred an indigenous-colonial Halifax game to Montreal. One can’t give birth to indigenous-colonial Halifax ice hockey without the Halifax-Dartmouth colonists. They only started showing up there on June 21, 1749. Therefore, Ice Hockey is not an amalgamation of games that somehow emerged around the world and Europe in particular. The stick game that became Ice Hockey is a unique, hybrid game that was born no earlier than the winter of 1749-50, literally .

2 of 4. What Halifax ice hockey had become by the time of the 1872–73 Montreal Transfer is a significant and separate consideration from Halifax ice hockey’s earlier Birth.

We know that the birth of Montreal ice hockey had to wait for Mi’kmaq sticks, literally. Therefore, James Creighton introduced Montrealers to what had become a Canadian-Mi’kmagi game by then, even if it wasn’t born that way.

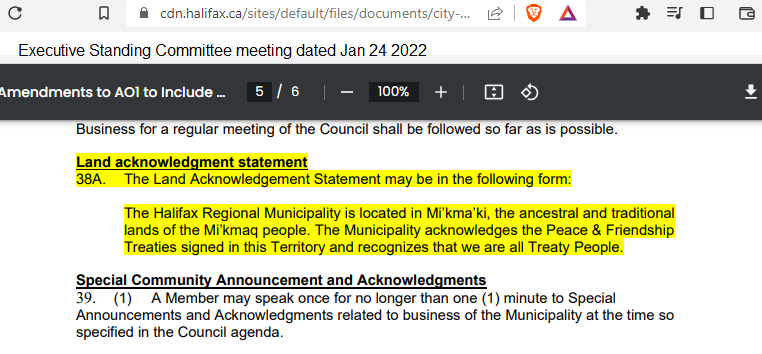

3 of 4. The Mi’kmaw’s involvement in pre-1872 Halifax ice hockey literally proves that Ice Hockey was born in Canada.

Were it not for the Mi’kmaw’s known presence in Halifax, the English invention theory may provide the best alternative interpretation. One could argue this, since the preponderence of hockey-related discoveries since the Internet points in this direction. It is very ironic that the English (only) theory was allowed to gain any traction, since Canadian hockey historians have known of the Mi’kmaw’s involvement in early Ice Hockey for at least 150 years. As we wrote to the Hockey Hall of Fame, the Governor General and Halifax’s city council and mayor, as of now no Canadian institution has formally recognized the Mi’kmaq First Nation for this epic contribution to Canadian culture.

4 of 4. The same sound logic that secures Canada’s rightful claim to being Ice Hockey’s birth nation must also apply to the Mi’kmaq First Nation.

The story of Ice Hockey’s birth and early evolution is a tale of two nations, literally. A novel conclusion, yes. But a sound one, given what we know about Ice Hockey’s Eden. It was very satisfying to learn that the Halifax Regional District supported this conclusion, indirectly, while I was preparing this essay:

3 of 3 HALIFAX’S TECHNOLOGICAL DISTINCTION

One more common generalization about Ice Hockey history needs to be addressed. In this way of thinking, Halifax’s lineal distinction doesn’t matter, even though it cannot be denied. Pre-1872 Halifax ice hockey was a big nothingburger. It’s entire legacy is no better than a one-off game played by royals in top hats. Halifax hockey doesn’t get special recognition because it doesn’t deserve any. James Creighton might just as well have introduced Montrealers to a random stick game from anywhere in Britain, or Kingston, Pictou, or Boston, an American city some four hundred miles south-west of Tuft’s Cove. That’s because “hockey” was all the same, you see, until the Montrealers got involved.

* THE “SAME GAME” GENERALIZATION

The now-popular belief that all pre-Montreal hockey-like games were the same seems to be the result of three forces that began coalescing just before the turn of the millennium.

The main driver was the mid-1990s introduction of the Internet. The digitization and widespread circulation of old periodicals proved that the concept of playing a ‘stick game on ice’ was not necessarily a Canadian creation. These new revelations called for a major reassessment of Ice Hockey’s presumed origins.

Around this time the Windsor, Nova Scotia, birthplace theory emerged. Widely promoted by Windsorites and local politicians, the Windsor theory soon became somewhat of a media darling. As such, there was considerable attention when, in 2002, some members of the Society of Hockey Research (SIHR) published a review of the Windsor birthplace claim. In making their assessment of Windsor, the SIHR members offered a definition of Ice Hockey that was based on two dictionary definitions.

“The wording we have agreed upon, borrowed or adapted from, in particular, the Houghton Mifflin and Funk and Wagnalls definitions, contains six defining characteristics: ice rink, two contesting teams, players on skates, use of curved sticks, small propellant, objective of scoring on opposite goals. Thus, hockey is a game played on an ice rink in which two opposing teams of skaters, using curved sticks, try to drive a small disc, ball or block into or through the opposite goals. (www.sihrhockey.org/__a/public/horg_2002_report.cfm:)

We suspect that this definition of Ice Hockey was of secondary importance to the SIHR members, whose main interest was the Windsor evaluation. Over the last quarter-century, however, the SIHR’s definition of “hockey” may have garnered more media attention than the Windsor evaluation. In many quarters, it has become the go-to way of describing all pre-Montreal versions of what we prefer to call hockey-like games.

In order to accommodate our reading audience then, we will sometimes use the SIHR’s definition of hockey. It has no effect on the practical and essential distinction. There becomes lineal hockey and non-lineal hockey. Lineal hockey refers to the singular game that all versions of modern Ice Hockey can be retraced to: the Halifax-Montreal version of “hockey” which became Ice Hockey in Canada by the end of the 1800s. This “lineal hockey” is what we have called Ice Hockey or “the stick game that became Ice Hockey.”

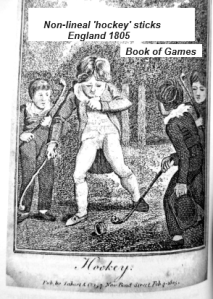

Non-lineal hockey refers to all of SIHR’s other “hockey” games. They are evolutionary also-rans in a 19th-century story of conquest that co-starred Halifax and Montreal only. In fairness, however, one might think that all pre-1872 ‘hockey’ games were the same, based on the preponderance of visual evidence that’s been discovered in the thirty years since the Internet’s introduction.

The two outer images on the three-part panel below are quite typical of what’s been uncovered over the last thirty years. The 1855 London image on the left is described as a ‘hockey’ game. We parked a modern shinty player in the middle panel, in order to ask two questions:

1- What game are the players on the right playing, ice ‘hockey’ or ice ‘shinty’?

2- What is each reader’s level of certainty?

It’s hard to tell, isn’t it? Welcome to the often vague world of 19th century ‘hockey’ evidence. Here’s an 1840s passage from Halifax, where one Mrs. Gould mentions hockey and a game called rickets. She is speaking about two different games here, and where the rules of English matter, the point is non-negotiable.

However, five sentences earlier in the same passage, Mrs. Gould says that rickets “is” hockey.

Starting with the first quote, if Mrs. Gould is correct in saying that hockey and rickets are different games, then she must have made some kind of mistake about saying hockey and rickets are the same game five sentences earlier. Or, one can reverse the logic where the latter statement is true. Or, and this is our position, one can conclude that Mrs. Gould’s description is not conclusive.

One conclusive thing that we do know is this: There was a stick game called rickets that was played in Nova Scotia during James Creighton’s childhood. And that stick game most closely resembles Irish hurling on ice, one of our British contender games. The following partial description of this version of rickets comes from a reporter who visited Nova Scotia. He wrote it for the Boston Evening Gazette, on November 5, 1859. The whole article can be found here. Byron Weston is about to move to Halifax. James Creighton is nine.

“From the moment the ball touches the ice, at the commencement of the game, it must not be taken in the hand until the conclusion, but must be carried or struck about ice with the hurlies. A good player – and to be a good player he must be a good skater – will take the ball at the point of his hurley and carry it around the pond and through the crowd which surrounds him trying to take it from him, until he works it near his opponent’s ricket, and “then comes the tug of war,” both sides striving for the mastery.”

In Byron Weston’s and James Creighton’s Halifax hockey, carrying the puck was expressly prohibited. That’s the one pre-1872 stick ball setting that matters, as we also saw in our first essay. That version of Halifax ice hockey was a different game than the Boston reporter’s rickets.

Next, imagine a world where 19th century descendants of Scots and Englishmen play shinty and grass hockey on ice (which they sometimes called bandy).

Which game is this?

We stress the ambiguity in order to avoid the inference that all pre-1872 Nova Scotia stick games were early forms of Ice Hockey. The image above reminds us that it would not be easy to tell when a game of English grass hockey was being played on ice versus a game of Scottish ice shinty. Likewise, during those stretches when Irish hurling players struggled for possession near goals, which were sometimes called rickets, during the “tug of war” phases, when the “ball” was on the ice.

There really is no need to try and make all pre-1872 stick games into one activity, hockey, as some have. The societal make-up of Halifax-Dartmouth strongly favours the opposite approach. Various stick games were played on the ice. Over time, ice hockey definitely became the dominant stick game around Halifax in the winter—after 1859, apparently, when rickets (hurling) reigned supreme.

It’s easy to see how the terms shinney and hurley became ways to refer to pond hockey, given their striking relationship to Scottish shinty and Irish hurling. The term rickets was surely borrowed from the game of cricket. From the Irish point of view, naming their ice game after such novel goals may have been a sensible way to distinguish ice hurling from proper hurling in casual conversation.

Mrs. Gould’s is a cautionary tale, or reminder that we must take care to not grant casual viewers infallible powers of observation, just because the speaker lived during this era. A very early witness to Montreal ice hockey infers that such rushes to judgment were quite predictable, even in 1877. I take these things to mean that the names associated with mid-19th century games may be less revealing than how the games played out – if that can be determined. For the record, the second London image is supposedly of a hockey game. So is the third, which is an 1867 image linked to Boston.

We can predict quite well how these non-lineal stick games played out: The various raised sticks and short stick-ends in the London and Boston images suggest that there would be lots of hitting and chasing the ball or puck. This would make sense, since 19th century grass fields used for shinty and grass hockey were up to 200 yards in length. Hitting is the only way to best direct a ball in such environments, which requires a short club-like end with some relative degree of thickness. On ice, however, such sticks condemn players to hockey purgatory, whether they know it or not. Their short ends preclude combination play and stickhandling. Defenders have little if any deterrent. The result is a roving, oafish pack game.

A GAME BASED ON SWEEPING

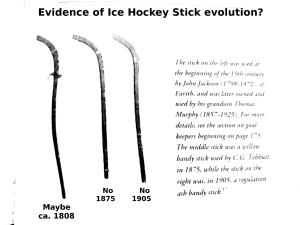

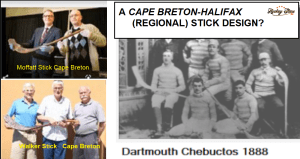

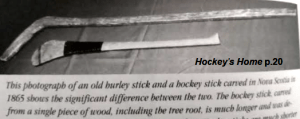

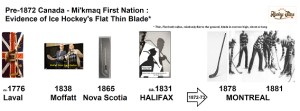

The photos below show examples of lineal sticks. They are ones that have what we called ‘flat thin blades’ in our Hall of Fame nomination essay. This is the stick-end that lives on in modern form.

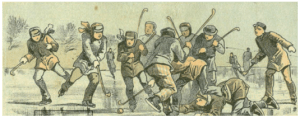

Both photos also show lineal Ice Hockey, because both photos are from Montreal. Dated to 1881, the left-side image is said to be the world’s oldest Ice Hockey photo. The other is from 1893, and shows a Victoria Skating Rink match in progress. Twenty years have passed since the Halifax-to-Montreal transfer.

As discussed in the first essay, James Creighton’s crucial relationship to Byron Weston proves that the Montreal players are playing an adapted version of Halifax ice hockey. In that stick game, a flat block of wood to be kept on the ice at all times.

Ice Hockey is about trapping, protecting and directing the puck better than one’s opponents on ice. Such an activity requires sweeping and, therefore, a well-proportioned, flat thin blade. Sticks that are adapted primarily for grass and hitting are non-optimal on ice. This is why they became non-lineal.

Turning back a little in time, to Halifax, the fact that the Mi’kmaw played with the colonists around Halifax is very significant, as affirmed in the split image above. On the left side, we have Byron Weston describing 1860s Halifax ice hockey. In the right-side article, the Mi’kmaw elder, Joe Cope, confirmed a few days later that he played with Weston. Cope’s mention of playing with Weston “and other old players” is very important, as it infers a setting where Halifax hockey was played on an ongoing basis. Cope implicates James Creighton, by extension. The two may have played together, although Creighton was around twenty-two when he moved to Montreal, and the extroverted Cope was around thirteen. It should also be noted that Cope spoke of ten-player teams, as only Weston’s details are usually mentioned.

If the Mi’kmaq game was based on its stickend, as we proposed, one would have a game that encouraged players to lean downwards, for the primary purpose of sweeping rather than hitting a puck-like object. Seen in the wider context, we have this indigenous game, versus three others that encourage hitting balls and lots of raised sticks. As such, the prohibition of raised sticks and carrying the puck may also read like old Haligonian: “Play your (ice) shinty and (ice) grass hockey and (ice) hurling elsewhere!”

Joe Cope’s involvement in Halifax ice hockey also reveals that others could play with Halifax-Dartmouth’s governing class. But, surely, only if they abided by the rules. Goons did not show up and flaunt the rules in the setting where the Westons and Creightons of Halifax-Dartmouth played. Few would have dared challenge the local authorities during that period in history. A slashing penalty could easily result in jail time, or worse.

But such insubordination was hardly necessary. We know that thousands of people skated around and in between Dartmouth and Halifax in the decades prior to James Creighton’s’ move to Montreal. If those who wanted to play like the London and Boston players could do so easily, elsewhere. Many would have done so gladly, because their vision of a ‘proper” winter stick game was based on grass hockey or shinty, or a proper game of ice hurling.

These considerations suggest that Halifax hockeyists like Cope, Creighton, and Weston would have been able to play their gentlemanly game in relative peace. The implications for the Halifax game are very significant. The Mi’kmaq sticks would have also enabled these Halifax hockeyists to evolve their game while other “hockey” players tripped over themselves using curved or crooked sticks.

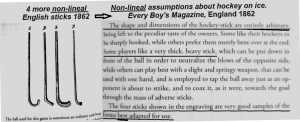

On that note, let’s circle back to the SIHR’s 2002 definition of hockey. Since it makes no distinction between playing sticks, it must follow that the 1805 sticks seen nearby are “the same” as Halifax’s entire pre-Montreal inventory. Likewise with the four 1862 English sticks shown below. The author who refers to them tells his English audience that one’s preferred stick-end is “entirely arbitrary.” We should mention that the four sticks are were placed in a discussion about grass hockey. We show them, however, only because they have been offered up as early ice hockey sticks. According to the SIHR’s 2002 definition of hockey, they must be, if they are used on ice with skates. That’s all that matters. Any and every curved stick will do.

With all due respect, any inference that all pre-Montreal “hockey” games were the same makes no practical sense.

And that’s partly because these four sticks are not “the same”…

… as this stick…

THE “HALIFAX TAKE-OVER”

1 of 3 – ICE HOCKEY’S REVOLUTIONARY STICK

As we noted in our first essay, The “flat thin blade” was the great civilizer of hockey played on ice. It tamed and domesticated the pucklike object, enabling “hockey” to evolve wherever it was played. During a time when Europeans and other Canadian colonists chased pucks, the Halifax and Dartmouth colonists began controlling and directing them from the start.

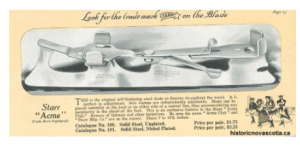

The Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw’s stick pre-empted the Halifax-Dartmouth colonists’ evolution. There was no need for those blue nosers to trip over themselves. Their lesson is our lesson: everywhere the flat thin blade went, it took over. Modern hockey players are proof of this. People have been led to believe that the ‘Micmac stick’ was just another brand, rather than the prototypical stick-end that inspired mass commercial imitation.

It’s very interesting to consider the scenario that Raddall presents (seen here on page 333) in his 1948 book, Halifax Warden of the North. His Halifax-Dartmouth officers “send” to the Dartmouth Indians (the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw) for their “necessary” sticks. It’s not difficult to imagine a Dartmouth officer telling a visiting officer about their game thusly: “We’ll ship you some Mi’kmaq sticks.” “How were those Mi’kmaq sticks?” Contrary to what one may think, there is actually very little evidence of the British playing grass hockey on ice prior to the mid-1700s. In due course, the term hockey would take over because of British colonization. However, a close look at how things began, in Halifax, and it may well have turned out that Canadian settlers would have said that Ice Hockey was a game played with a Mi’kmaq stick. That would have cleared up a lot of confusion.

It’s very interesting to consider the scenario that Raddall presents (seen here on page 333) in his 1948 book, Halifax Warden of the North. His Halifax-Dartmouth officers “send” to the Dartmouth Indians (the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw) for their “necessary” sticks. It’s not difficult to imagine a Dartmouth officer telling a visiting officer about their game thusly: “We’ll ship you some Mi’kmaq sticks.” “How were those Mi’kmaq sticks?” Contrary to what one may think, there is actually very little evidence of the British playing grass hockey on ice prior to the mid-1700s. In due course, the term hockey would take over because of British colonization. However, a close look at how things began, in Halifax, and it may well have turned out that Canadian settlers would have said that Ice Hockey was a game played with a Mi’kmaq stick. That would have cleared up a lot of confusion.

Our perceptions of history are often based on what is forgotten and what is discovered. The Moffatt stick was presented to the public after the SIHR offered their 2002 definition of Ice Hockey. So were two others in the following years, the Walker and Laval sticks. We consider all three to be “the same” because each features a relatively well-proportioned, flat thin blade. It’s not difficult to see how such a device became “dominant” on frozen ponds and lakes when one considers the competition or, namely, the evidence of sticks we have that preceded the Halifax-to-Montreal transfer. And since Montreal ice hockey claimed the national definition of Ice Hockey in part through Halifax ice hockey‘s flat thin blade, a very significant question follows:

Who introduced the flat thin blade to Halifax ice hockey?

There are two continents to consider.

1 of 2 – EUROPE-BRITAIN

The flat thin blade could have been imported to Halifax from Europe. The earliest European-British flat thin bladed stick that we know of was owned by one John Jackson who was born near Cambridge, England. We’ll call his device the Cambridge stick and date it to Jackson’s 10th birthday. Seen on the far left of the image below, Europe’s and Britain’s oldest ‘flat thin’ blade dates to around 1808. This is well before the Halifax-to-Montreal transfer of 1872-73, meaning that such an European stick could have reached Halifax before then in theory.

In the Cambridge stick’s case, we have no Henry Joseph-like proof of transfer. That would be ideal, if one wanted to make the argument that the English introduced the flat thin blade to Halifax ice hockey. Nor do we have any testimony where Jackson writes that he or a colleague personally delivered the flat thin blade to Halifax-Dartmouth. Nor do we have any other English claim to that effect. It’s only possible in theory that an English flat thin blade could have made its way to Halifax, before James Creighton moved to Montreal.

Having no specific claim to address, we must try to make the best generalization as to how the Jackson stick could have merged with pre-1872 Halifax ice hockey. Then we must also ask if the interpretation seems strong or weak, because not all generalizations are equal.

Cambridge, England is said to have been involved in Bandy’s evolution prior to that game’s formalization at Oxford in the late 1800s. Cambridge and Oxford are also home to two of England’s finest schools, where English military officers were often educated. We also know that stick ball on ice was played at Lord Stanley’s Eton before 1872.