On December 7, 2021 I submitted a pdf version of this essay to the Hockey Hall of Fame’s then Selection Committee. A day later, I also submitted the to the Governor General, suggesting that she consider conferring some sort of honour to the Mi’kmaw for their epic contribution to Canadian hockey.

This essay is also available in pdf form here, and as the first essay in my free book, The Four Stars of Early Ice Hockey.

Mark Grant, 2024.

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this nomination essay is two-fold. First, it recommends the induction of the Mi’kmaq First Nation into the Hockey Hall of Fame’s Builders category. Alternatively, the petitioner respectfully asks the Hall to once again consider suspending its usual custom of recognizing only individuals, for the purpose of creating a special place for the Mi’kmaq, owing to the exceptional nature of this indigenous group’s contributions to the birth and early evolution of ice hockey.

This petitioner believes that the Mi’kmaq First Nation’s contributions to ice hockey extend beyond what he offers as grounds for their rightful and greatly belated recognition by the Hall. In this essay, however, he only asks that the current Selection Committee consider their induction on two grounds: for being renowned craftsmen of many of ice hockey’s earliest sticks in fact, and for possibly being the inventors of the prototypical ice hockey stick.

1 OF 2 – THE MI’KMAQ AS CRAFTSMEN – Note: to jump forward in this presentation from section to section, search ##

I will start this two-part nomination with what appears to be beyond dispute. Hockey historians have long since acknowledged that the Mi’kmaq crafted many of ice hockey’s earliest sticks. This aspect of their rich legacy has been widely known for well over a century by now, or decades prior to the Hockey Hall of Fame’s founding over seventy years ago, in 1943.

No serious national discussion has ever taken place as to what this craftsmanship designation alone infers. I will address that matter near the end of Part One of this nomination. However, in order to begin to understand the magnitude of the Mi’kmaq’s contribution, we must first mention some basic hockey history and how its traditional portrayals routinely inhibit this same discussion.

ICE HOCKEY’S TRADITIONAL HISTORICAL THEORY ##

As far as stick-making is concerned, in the traditional versions of hockey history the main actors are seen to have come from Ireland, Scotland and England in the 18th and 19th centuries. Prior to this time the ancestors of Canada’s Irish and Scottish settlers had played stick games known as hurling (Ireland) and shinty (Scotland) for thousands of years. Field hockey, the English stick game, is thought to be younger but was surely played for some time before Halifax, Nova Scotia’s founding on June 21, 1749. That date is very important to the ice hockey stick’s evolutionary question, for being the generally accepted earliest possible time when British settlers could have begun determining the prototypical ice hockey stick’s design.

After the ice hockey stick (somehow) evolved (exclusively) from Britain’s old country sticks, the colonists who were involved in this process later decided to hire the Mi’kmaq to craft these devices of theirs – the colonists’ – invention. The colonial inventors of the prototypical ice hockey stick are never identified specifically, and perhaps because they are mythological figures. For this reason one might say that this aspect of the traditional theory is unhinged, in the sense that no direct linking evidence is ever provided. Nonetheless, a demonstrable colonial-indigenous partnership did in fact occur, and lasted from sixty to around one hundred and eighty years, depending on the source.

At first glance the notion that the ice hockey stick evolved from hurling, shinty and field hockey makes great sense. It does, given the obvious similarities of these stick games to ice hockey and owing to Britain’s very strong relationship to colonial Canada. But the same theory only makes especially good sense when the Mi’kmaq’s potential contributions to the invention question are downplayed or ignored. Once the Mi’kmaq are introduced a serious problem is raised, for then one must ask: If the colonists invented the prototypical ice hockey stick, why did they next have the Mi’kmaq craft sticks of their invention?

Why has this question gone unanswered for so long, since we know that the Mi’kmaq crafted many of ice hockey’s earliest sticks? This writer sees two likely clauses. Both represent trends in reflexive “dominant” thinking that play out at the cultural level and obscure the Mi’kmaq’s true involvement. The first trend, just alluded to, is what he thinks of as The Pre-1872 Colonial Bias or the long-standing tendency to frame ice hockey’s pre-1872 era in predominantly colonial terms.

I am certainly not immune to this effect. It caused me to overlook and downplay the Mi’kmaq’s indigenous contributions for years. When given the attention it truly deserves, the Mi’kmaq’s contribution to Canadian culture is difficult to overstate.

What the Mi’kmaq seem to say about their history provides a compelling answer as to why the colonists hired them to craft their sticks in the first place: They did so because the Mi’kmaq had been playing a stick game on ice prior to the British colonists’ arrival in 1749, and the colonists liked their – the Mi’kmaq’s – sticks. The pre-1749 existence of such an indigenous game steers the imagination to a time that must precede the era when the colonists began hiring the Mi’kmaq to make their sticks. At first the colonists traded for these indigenous sticks. Later on they hired the Mi’kmaq to craft the same devices. In this reckoning there may be no need to involve Britain’s old country playing sticks whatsoever.

AN INDIGENOUS-COLONIAL CLAIM ##

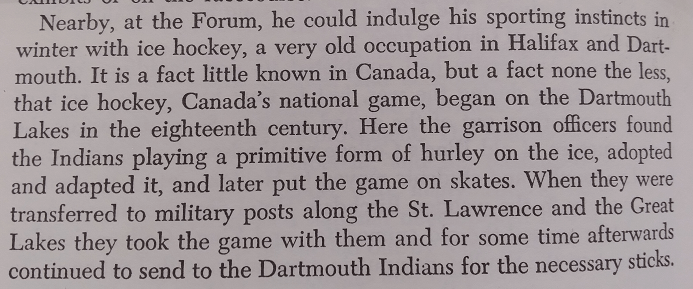

I next turn to a claim that has been around now for over seventy years. Many hockey historians know of it. Few hockey fans will, however, because historians rarely mention it and since it amounts to a single paragraph in a 333-page book that is otherwise not about about ice hockey, Halifax: Warden of the North. The passage below was published in 1948 and written by one of Nova Scotia’s most noted historians, a multiple Governor General’s Award recipient and Order of Canada member, Thomas Raddall:

For the benefit of those with little or no understanding of ice hockey history, I should briefly point out Raddall’s readers knew exactly what Raddall was talking about in describing the origins of ice hockey. By 1948 much of the sport’s evolutionary path was quite well known. The National Hockey League (NHL) had owned the professional market since 1926. Olympic ice hockey had been around since 1920, the Stanley Cup since 1893. Much was known to have happened since James Creighton’s big move from Halifax in 1872. But in this writer’s opinion it was during Montreal’s Winter Carnivals from 1883 to 1889 when Montreal claimed the title ice hockey by public acclimation.

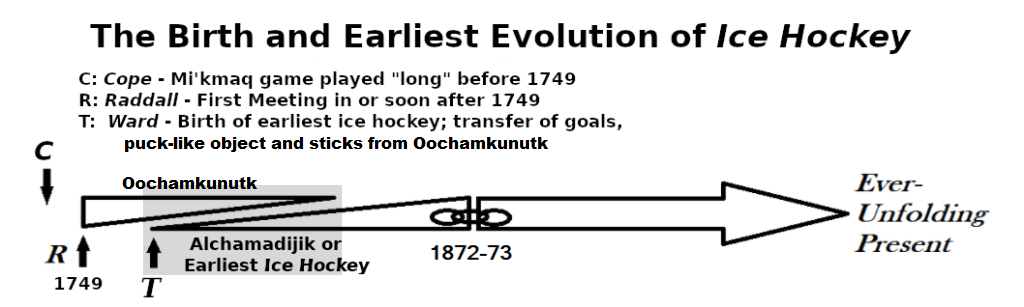

Capturing a title is not the same thing as invention, however. In order to fathom ice hockey’s true birth, Raddall is telling the reader to look further in the past beyond 1872, and to the lakes of Dartmouth. The “Indians” to which he refers were from the Mi’kmaq First Nation. They were very possibly first seen playing their ice game along the Halifax-Dartmouth harbour at a place called Tuft’s Cove. The “primitive form of hurley” that the Mi’kmaq were seen playing appears to have been called Oochamkunutk* which Raddall’s British officers later adapted into a new game that the Mi’kmaq appear to have called Alchamadijik* – a very specific game that would (much) later claim the title of ice hockey.

Moving forward, I will ask the Selection Committee members bear with me, as I strive to emphasize that my interpretations are just that, interpretations. I will use asterisks * whenever I comment on what I believe the Mi’kmaq are saying. Such commentary must ultimately be confirmed by the Mi’kmaq directly, of course.

Raddall’s claim fundamentally differs from the traditional ‘colonial’ theory by describing an indigenous-colonial birthing process. Of the two, it alone explains the original demand for Mi’kmaq crafted sticks with persuasion, pointing to a beginning that must precede the traditional narrative by decades. In the traditional reckoning colonists must first decide to begin evolving their old country sticks into the ideal hockey stick prototype. Such a process would take time, only to be followed by the unexplained matter of the colonists deciding to hire the Mi’kmaq to make ‘their’ sticks.

In Raddall’s way of thinking the officers wanted the indigenous sticks from the time they first saw them, at what I call the First Meeting or when his officers first saw the Mi’kmaq playing their ice game. This distinction calls to mind something else that has hindered our appreciation of the Mi’kmaq: the Western thinkers’ tendency to define the parameters of eras by the earliest hard evidence. Until very recently, the earliest such evidence in ice hockey only lead back to the early 1800s. Raddall’s claim compels one to look much further into the past.

THE 1749 TO 1761 ERA ##

It’s possible, although by no means certain, that the First Meeting took place in the winter 1749-50. The British would have thoroughly surveyed the lakes of Dartmouth prior to Halifax’s first winter, following their arrival in the summer of 1749. They would have known whatever Mi’kmaq settlements were nearby, and could have seen the Mi’kmaq playing their stick game on Dartmouth’s frozen lakes prior to Dartmouth’s founding in 1750.

However, by Halifax’s first winter the Mi’kmaq and the British were not getting along, to say the least. Circumstances were not conducive the friendly game of pond hockey that Raddall’s idyllic description infers. The First Meeting might not have occurred until after June 25, 1761, as that appears to be when lasting peace was finally established between our colonial and indigenous parties*. From this I have come to conclude that Raddall’s First Meeting most likely occurred in the 1749 to 1761 era, which I sometimes refer to as circa 1749.

Thomas Raddall’s indigenous-colonial claim is, not surprisingly, well supported by the testimony of a Mi’kmaw elder, Joe Cope. Cope is widely quoted as telling a Halifax newspaper in 1943, of ice hockey’s true birth: “The honor and credit wholly belongs to the Micmac Indians of this country, for long before the pale faces strayed to this country, the Micmacs were playing two ball games – a field and ice game.” This has been taken to mean that Cope was saying that the Mi’kmaq ice game was a precursor to Halifax ice hockey. While I do agree with this general conclusion I must mention that Cope’s submission to the Halifax newspaper is more detailed than most presently think and, frankly, confusing in certain points.

The only place that I have ever seen Joe Cope’s full quotation is in a video that was produced by two of his great-great granddaughters, April and Cheryl Maloney, The Game of Hockey – A Mi’kmaw Story. I discuss the larger Cope quote in this two-part nomination’s conclusion. For now I note that his testimony supports the idea of colonists seeing the Mi’kmaq game very soon after their arrival in 1749: After all, since we know that Canadians play hockey from winter to winter every winter, one should expect that the Mi’kmaq could have also been seen doing the same thing very early on, since Cope says that their winter game was played “long” before the Halifax-Dartmouth colonists arrived. Such an early discovery would precede the founding of alum Thomas Chandler Haliburton’s King’s College in Windsor in 1789 by thirty to forty winters.

THREE ETERNAL HOCKEY FIXTURES ##

There are two versions of the Maloney’s video. April and Cheryl have given me consent to mention the free version, where someone filmed an earlier version of the one I have just mentioned. With their further consent I have linked to the free video later on in this nomination essay. For now, the curious reader should know that the free version is very similar to the main one, although there are some significant differences.

Both versions introduce another Mi’kmaq First Nation member, Jeff Ward, who shares a presumably* old story regarding the origin of the Mi’kmaq’s ice game. The game Ward describes involved three of ice hockey’s most fundamental fixtures: goals, a puck-like object and a stick like today’s hockey stick. In order to appreciate the potentially immense significance of those details, to ice hockey history, one first must recall Raddall’s claim and our Order of Canada historian’s specific use of the term adapted. Next, one must consider the same claim with attention to the fact that the term adapted always infers two things:

(1) The officers’ new game was somehow different than the earlier one and

(2) Some elements of the former game must have been transferred to the new game.

Since Ward tells us that Oochamkunutk involved goals, sticks and a puck-like object, it follows that all three must have been transferred to Alchamadijik from Oochamkunutk at the time of Alchamadijik’s birth. Consider the only three possible alternatives. Would Raddall’s officers have begun playing their adapted game:

(1) with sticks and a puck-like object but no goals?

(2) or, with goals and sticks but no puck-like object?

(3) or, with goals, a puck-like object but no sticks?

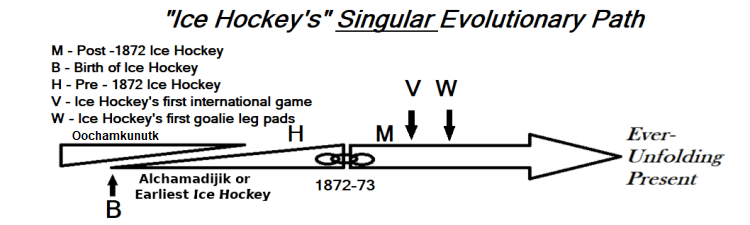

Hardly. Nor would it make any sense to suggest that any of these elements ‘may’ have removed at some point following the introduction of Alchamadijik, ‘for a time, perhaps,’ since ‘we just don’t know’. What occurred from the time of Alchamadijik‘s birth on the lakes of Dartmouth until James Creighton introduced an adapted version of the same game in Montreal after 1872 must reflect what we know has occurred ever since: Sticks, goals and puck-like objects have always been present in ice hockey. This summarizes why I personally believe the Mi’kmaq are the “first” builders of ice hockey, for having introduced things from an earlier game that have remained ever since they were transferred to the very game, Alchamadijik, that later claimed the title of ice hockey by public acclimation in Montreal. Here’s Raddall’s broader colonial-indigenous take in diagram form:

LINKING EVIDENCE ##

I must emphasize that my own conclusions rely on Halifax-Dartmouth ice hockey being unique. This distinction should be addressed because over the last two decades some writers have suggested that “ice hockey” was played in various settings throughout colonial North America and in Great Britain during the same period, prior to 1872. This way of thinking may have been introduced around twenty years ago now, by a quite well-known group of researchers called the Society of International Hockey Research (or SIHR). In the SIHR’s treatment of early ice hockey all of the settings they mention are granted the same status as Halifax-Dartmouth ice hockey’s entire pre-1872 legacy, for sharing in common the SIHR’s definition of what constitutes ice hockey. From this the SIHR, or some SIHR members, have concluded that ice hockey was invented in England.

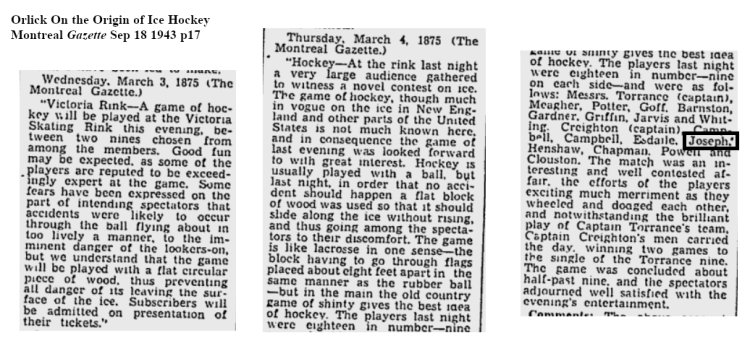

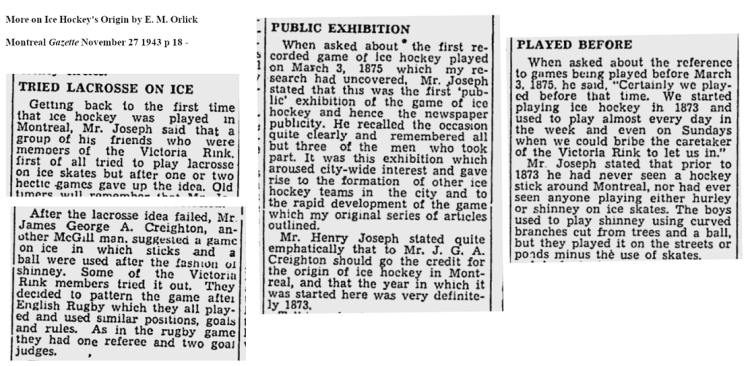

Here it helps a great deal to know about Henry Joseph. This well-known Montreal athlete became a close peer of Creighton soon after the latter’s move from Halifax in 1872. Joseph is an extremely important historical person, as the following article from the Montreal Gazette makes clear. In it he is seen to have played alongside Creighton in the famous demonstration match that was played on March 3, 1875 at Montreal’s Victoria Skating Rink (VSR). Seen by around forty spectators, this match is said to have inspired a city-wide interest in ice hockey in Montreal. As Canada’s national pastime caught on there it soon spread to other areas in present-day Ontario and Quebec and then across Canada.

Contrary to what some have said, (and this much does not seem to include the SIHR), the March 3, 1875 match cannot represent the birth of ice hockey. For one thing, by March of 1875 Montreal ice hockey had been around for at least two winters. Henry Joseph describes that birth in another Gazette article, seen below. In addition to describing the circumstances that led to ice hockey’s Montreal introduction, our direct eye-witness also “emphatically” singles out Creighton and Halifax in the process. (For where I am going in the second part of this nomination essay, I must emphasize that Joseph clearly states that there were no hockey sticks in Montreal until Creighton imported some from Halifax.)

Henry Joseph’s testimony offers that which seems to make Halifax-Dartmouth entirely unique: it amounts to hard evidence that “links” pre-1872 Halifax ice hockey to the sport’s subsequent developments in post-1872 Montreal. Of all the pre-1872 settings that we know of, only Halifax-Dartmouth seems to offer such direct linkage, which it does in many ways. There is a profound difference between narratives that link to the past via hard evidence and those that do not. In the latter sense the English invention theory seems rather like the traditional view of ice hockey history, where we are only told that colonists evolved the ice hockey stick from their old country devices. Despite this, when one looks back in time beyond “the Great Wall of 1872”, the hard linking evidence seems to point in one direction only: to Halifax-Dartmouth and an indigenous-colonial birthing narrative.

Finally, I wish to point out to the Selection Committee and anyone else reading this that I may be incorrect on this vitally important point. If I am, hopefully others will come forward with similar evidence that directly links other pre-1872 settings to ice hockey’s subsequent evolution in Montreal. Or, is there really no such evidence?

THE DEFINING OF A SINGULAR EVOLUTIONARY STREAM ##

Earlier I suggested that ice hockey became recognized as the ever-evolving game we know today in Montreal during the Winter Carnival era of 1883-89, which began nearly ten years after the famous demonstration game at the VSR in March of 1875. When Carnival visitors came to Montreal, as they did from many places in North America, and saw ice hockey being played, they returned home with a very specific vision of how this “new” game was played. They didn’t care where earlier iterations of the same activity originated from much earlier. Nor did anyone likely tell them.

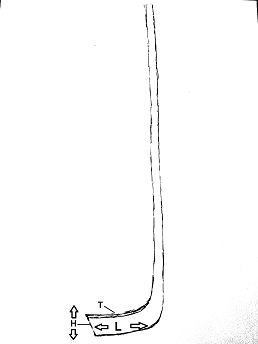

Nonetheless, when Montreal claimed the title of ice hockey by public acclimation, Halifax laid claim to the same tradition’s birth retrospectively, for having given birth to the singular evolutionary stream that Montreal inherited at a later time. This inheritance, or transferring, is represented in the next image by the chain that links H (Halifax) to M (Montreal). It’s a very important transition point to recognize for the sake of this nomination, because the link highlights a known stick-making legacy that begins with the Mi’kmaq in Halifax prior to 1872 before going on to include Montreal and later the rest of Canada until the 1930s.

ICE HOCKEY AND A TELEPHONE ANALOGY ##

The consequences of Montreal’s victory in ice hockey are not unlike the difference between the histories of the telephone versus telephonic devices. It took some time after he first invented or birthed his famous device until Alexander Graham Bell won the title, telephone, by cultural consensus. When this occurred a singular evolutionary path emerged that lead back in time and space to the summer of 1874 and Brantford, Ontario. The social convention that compels us to think of Bell’s singular achievement explains why it seems most correct to say that Guglielmo Marconi and others invented telephonic devices, and incorrect to say that Marconi and others also somehow invented the telephone. This remains true even if those other inventors called their devices “telephones” and even if their devices were superior to Bell’s invention – because Bell won that title by public acclimation. However, when one considers the evolutionary stream that similarly earned the title of ice hockey, a strong argument can be made that it won by public acclimation in no small part because of its demonstrably superior sticks. I will explore that idea in the next part of this nomination.

I don’t wish to sound overly critical of the SIHR here. Canadians should know that members of this international group have gone to significant lengths to make sure that hockey sites and persons of consequence are enshrined, rather than forgotten. As one who appreciates ice hockey history, I am truly thankful that they have done these things, which I understand SIHR members have sometimes done at their own personal expense. Nonetheless, the various English settings that the SIHR promote as examples of early ice hockey are the telephonic devices of this analogy. It is beside the point that their players may have called their games hockey, or their sticks hockey sticks. Those settings must earn their way into the evolutionary stream through linking evidence. Halifax earned this setting’s birthing claim once Montreal claimed the title of ice hockey, just as Brantford earned the same with the telephone. Later on Winnipeg (as indicated by the W in the diagram above) earned its way into the same evolutionary stream for having introduced ice hockey’s first goalie leg pads in a Stanley Cup game through George Merritt in 1896. Ten years earlier, Burlington, Vermont (V) similarly earned the right to call itself the home of ice hockey’s first international game. To my understanding no English setting has similarly earned their way into the same evolutionary stream, before or after 1872. This is only suggested, and suggested often.

The SIHR has certainly made another significant contribution over the last two decades by thoroughly dispelling what turned out to be a long-held myth: that colonial Canadians were the first to think of playing stick games on ice. The ongoing digitization of old periodicals ensures we can expect more of the same discoveries to continue. But these other games mustn’t be conflated with ice hockey or ice hockey’s evolution until they earn their way into that singular evolutionary stream. Until then they must be regarded a different study, something like an exploration of telephonic devices versus the telephone. The settings that the SIHR has been saying are ice hockey are instead, if only in this writer’s opinion, stick games played on ice.

SAMPLES OF EVIDENCE ##

This leaves only two birthing theories that have earned further consideration through recognizing the vitally important uniqueness of the Halifax-Montreal transition. There is the claim – Raddall’s and the Mi’kmaq’s* – that the Mi’kmaq invented the ice hockey stick which they later crafted for colonists. There is the traditional theory in which Canadian colonists invented the hockey stick which they later hired the Mi’kmaq to craft. Both acknowledge that the Mi’kmaq were craftsmen of great consequence in ice hockey’s earliest eras. This is also something we know for many reasons. However, as a solo researcher with no great scholarly knowledge of this subtopic, I can only offer the Selection Committee some of the evidence.

As we have seen, Thomas Raddall’s claim attests to the Mi’kmaq’s role as craftsmen through their ongoing demand for the latter’s “necessary” sticks. So do Joe Cope’s and Jeff Ward’s indigenous testimonies, along with those of other Mi’kmaq in April and Cheryl Maloney’s videos.

On page 53 of Hockey’s Home – Dartmouth-Halifax Martin Jones writes that “…Micmac sticks appeared in newspapers commencing in the 1860s” or prior to that most important transitional year, 1872. On the previous page Jones mentions Dr. John Martin, another Nova Scotia historian of note, as saying in “Hockey in the Old Days,” that he [Dr. Martin] was told by one Isaac Cope that “his [Cope’s] people made hundreds of hurleys around Lake Micmac every season. They were shipped all over the Maritimes, and even to Montreal. One of the biggest buyers locally was the Starr Manufacturing Company, who wholesaled them to hardware merchants hereabouts, and shipped large quantities to their branch office in Toronto.”

In 2019 Nova Scotia Hockey historian David Carter told the CBC: “One of the most important records that I found from Indian agent records is from 1909-10, for the Colchester district, in which the agent claimed that they made a thousand dozen sticks. That’s 12,000 sticks,” said Carter. “It’s definitely something to be celebrated. It’s such a rich history.”

Indeed, and Jones tells us that Byron Weston, a close peer of Creighton and one-time president of the Dartmouth Amateur Athletic Association, said in the 1930s that “it may not be generally known that for many years sticks manufactured by these Indians have been shipped from here to the Upper Provinces and the United States.”

I would think that the Hall has many “Micmac” sticks in its inventory, as would various museums including the one in Windsor, Nova Scotia seen in April and Cheryl Maloney’s videos. One very strong-looking candidate is shown nearby, the McCord stick from Montreal. Dated to 1878, we should ask if it fits the known Mi’kmaq profile.

CONCLUSIONS OF PART ONE ##

The bottom line in Part One of this nomination seems irrefutable. We have known for many decades that Mi’kmaq-crafted sticks were distributed throughout Canada from at least the 1800s and all the way into the 1930s. At a minimum this makes the Mi’kmaq craftsmen of great consequence to early ice hockey.

But how many have paused to reflect on the ramifications of this truth?

Let’s do that now. When the Mi’kmaq are considered as craftsmen alone, I submit to the Hockey Hall of Fame’s Selection Committee that all of the following conclusions are inevitable:

1a. If the “traditional” theory is correct, and Halifax-Dartmouth colonists merely hired the Mi’kmaq to craft sticks of their – the colonists’ – invention prior to 1872, then the Mi’kmaq must have played a major role in the early development of ice hockey history, as either exclusive suppliers of Halifax-Dartmouth sticks or as significant producers of the same.

1b. Raddall’s account leads to the same conclusion, adding that the Mi’kmaq crafted and invented ice hockey’s earliest sticks.

2. As ice hockey began spread elsewhere in Nova Scotia and throughout the network of military outposts described by Raddall, the Mi’kmaq would have been significant craftsmen of those earliest sticks, and likely exclusive suppliers in the earliest parts of those phases.

3. If James Creighton ordered Mi’kmaq-crafted sticks from Halifax, then the birth of ice hockey in Montreal either entirely or significantly relied on the same indigenous devices, as did the further expansion of early ice hockey in Montreal.

4. Since Montreal’s first Winter Carnival in 1883 included a team from Quebec City, it becomes highly likely that Mi’kmaq-crafted sticks were also exclusively or significantly involved in the birth of ice hockey in Quebec City too.

5. Likewise with Ottawa, which fielded a team in the second Winter Carnival.

6. And in Kingston, and in Toronto, and in parts nearby during this same early era.

7. The same must have been true as Canada’s new game spread ever-westward and throughout the Atlantic provinces over the ensuing decades. Canadians’ demand for Mi’kmaq-crafted sticks continued well past the arrival of the first transcontinental train in Vancouver in May of 1887, and even beyond 1926 when the National Hockey League gained control of the professional hockey market.

8. By the end of the 19th century Mi’kmaq-crafted sticks had very likely found their way to the United States and Britain. Some Canadians probably used them the first National Hockey League games, in the earliest International Ice Hockey Federation tournaments, at the introductions of Olympic ice hockey in 1920 at Antwerp, Belgium and at the first Winter Olympics in Chamonix, France in 1924. Given what we know, we should not be surprised if players from other nations did the same.

I could not agree more than I do with David Carter, who said that this enormous legacy should be celebrated. I will end Part One of this nomination by respectfully submitting to the Selection Committee that the Mi’kmaq First Nation’s induction into the Hockey of Fame’s Builder’s category as craftsmen is not only fitting, but long overdue beyond a reasonable doubt.

2 of 2 – THE MI’KMAQ as INVENTORS ##

Near the start of the previous section I went out of my way to avoid seeming like I was speaking for the Mi’kmaq, by cautioning the reader with asterisks (*) whenever I wrote something that I believe they are saying. In the same spirit I will begin this section by mentioning another thing that seems quite obvious to me. The Mi’kmaq claim to be more than merely the craftsmen of ice hockey’s earliest sticks. They also appear* to claim to be the ice hockey stick’s inventors.

This comes up early in both of April and Cheryl Maloney’s videos when Jeff Ward tells the story of a deity named Glooscap’s triumph over the god of winter. After winning that first ice game (with an archetypal blazing shot) , Ward tells us that Glooscap “took that stick, which is known now today as a hockey stick” to share the ice game with the Mi’kmaq people. Likewise, a couple of minutes later Vernon Gloade claims that the Mi’kmaq had sticks “like hockey sticks” by the time the British arrived.

In my opinion the best first question to ask is if the Mi’kmaq claim to have invented the prototypical ice hockey stick. If they did, it would seem to follow that all subsequent variations made by colonists and early Canadians would, by definition, be adaptations of the same indigenous prototype.

LEGAL CONSIDERATIONS ##

This petitioner considers it likely that Canada’s Supreme Court would very likely accept such testimony, if the Mi’kmaq do indeed claim to have invented the prototypical ice hockey stick. Recent indigenous judicial decisions that suggest this outcome may have begun with Delgamuukw v. British Columbia in 1997. In Delgamuukw Canada’s highest court said that indigenous oral histories must be given the same consideration as traditional forms of historical evidence:

87 – “Notwithstanding the challenges created by the use of oral histories as proof of historical facts, the laws of evidence must be adapted in order that this type of evidence can be accommodated and placed on an equal footing with the types of historical evidence that courts are familiar with, which largely consists of historical documents.“

Such broad definitions are often refined or “narrowed” in court later decisions, as seems to have happened in this case a few years later: “After Delgamuukw, a number of court cases have further defined how to interpret oral histories as evidence in court. In Squamish Indian Band v. Canada (2001 FCT 480) and R. v. Ironeagle (2000 2 CNLR 163), the court accepted oral histories as evidence but stipulated that the weight given to oral histories must be determined in relation to how they are regarded within their own societies.” In layman’s terms one must ask, If the Mi’kmaq do indeed claim to have invented the ice hockey stick, how important might such an invention be regarded by members of that indigenous society?

Somewhat surprisingly – and even though we are talking about Canadian society – the answer is, That depends. Here one must keep in mind that many Canadians have no interest in ice hockey whatsoever. If those Canadians were to be asked how important ice hockey is in Canada, many would likely say, “I don’t know, and I don’t care.” From such a sample one might conclude that Canadians in general don’t care about ice hockey. Yet the Selection Committee knows that ice hockey is a major pillar of Canadian culture. So the better, narrower question becomes, How strongly do ‘hockey people’ in Canada feel about ice hockey?

And in this discussion one must ask, How strongly do ‘hockey people within the Mi’kmaq community’ feel about the matter of who invented the prototypical ice hockey stick?

“NECESSARY” STICKS ##

Throughout the second part of this nomination I pursue a similar question: Can it be determined, on the balance of probabilities, that the Mi’kmaq First Nation did invent the prototypical ice hockey stick? If they did, it would seem to follow that all subsequent variations made by colonists and early Canadians would, by definition, be adaptations of the same indigenous prototype. The same must apply to every modern hockey stick that is presently being used or sold on the global market today.

In approaching that mystery I next recall the previously introduced claim by Thomas Raddall, asking another question: What did our Order of Canada historian mean when he spoke of the Mi’kmaq First Nation’s “necessary sticks”? This writer sees only two ways that necessary can be applied in the passage below.

1 of 2 – In the first interpretation Raddall used the term “necessary sticks” because the officers had no playing sticks of their own, nor did the officers at the other military posts.

This seems the least likely of the two scenarios because, in the “traditional” view of ice hockey history, it is often noted that British settlers brought their ‘old country’ playing sticks with them when they moved to colonial Canada. This precedent doesn’t need to have begun with the founding of Halifax on June 21, 1749 either. Britain’s colonial era began around 1500, globally, and about one century later in North America. The custom, within the military, of bringing playing sticks to faraway places may have preceded the arrival of Raddall’s officers by centuries.

2 of 2 – In the second definition Raddall’s officers considered the Mi’kmaq sticks “necessary” because they were much better than each of Britain’s old country sticks at the tasks of controlling, protecting and directing puck-like objects on ice.

Here we grant, for the sake of discussion, that some of Halifax’s earliest settlers or military members did indeed bring over their playing sticks. Some may have brought along Irish hurleys (used for hurling) or Scottish camans (for shinty), but the first old country sticks seen around Halifax would have been almost exclusively of the English variety used for field hockey. We can be certain of this because Raddall reports that the vast majority of Halifax’s nearly 3,000 first settlers had responded to a March 1749 advertisement in the London Gazette.

Given this much information alone, it would be reasonable to expect that only English field hockey sticks crossed over on the inaugural voyage. However, Raddall later reports that about one hundred military members joined the first expedition, so one should further ask if those British military members were exclusively English. Lastly, and as noted in the previous section, one must take into account the very real possibility that Raddall’s friendly “First Meeting” between the officers and Mi’kmaq may have had to wait until after Halifax’s first winter in 1749-50 and perhaps as late as 1761. What was the composition of British officers during that twelve-year period? The surprisingly detailed list Raddall provides regarding Halifax’ initial settlers (below) raises the possibility that military historians might be able to answer that question quite specifically.

THE PROTOTYPICAL ICE HOCKEY STICK’S ‘NECESSARY’ FEATURES ##

What Raddall meant by “necessary” is a mystery. However, if the Mi’kmaq’s sticks were required because of their superior usefulness, as in the second definition, we may be able to determine why they were seen as necessary in a practical sense. The next question to ask is, What exactly makes an ice hockey stick unique?

Around twenty years ago The Society for International Hockey Research (SIHR) concluded that “Hockey is a game played on an ice rink in which two opposing teams of skaters, using curved sticks, trying to drive a small disc into or through the opposing goals.” This broad definition is certainly useful for some grouping purposes, yet it fails to recognize that ice hockey has always demanded something much more than a “curved” or ‘crooked” stick.

The shaft, so generally common to other playing sticks, is not the best place to make such a determination. One must focus on the stick’s end. The prototypical ice hockey stick’s end has five necessary requirements. All must be present. The consequences of violating any one of these requirements will prove severe. The proof of these elements’ “necessary” nature rests squarely on the fact that each has been carefully preserved in every ice hockey stick we know of, from the ones sold today in an ongoing legacy that dates back in time beyond 1878 and Montreal’s McCord stick.

What all known ice hockey sticks share in common is shown in the sketch below. The prototypical ice hockey stick requires: a relatively well-proportioned, relatively thin blade with a relatively flat base and two flat sides. Going forward I will generally refer to this combination of the five necessary elements the prototypical ice hockey stick’s flat thin blade.

Every hockey person living today has known nothing but the ‘flat thin blade’, as did their parents, and their parents’ parents and so on. Watch a hockey game with attention to the players’ stick-ends and in less than thirty seconds it will become evident that the game of ice hockey is largely predicated on the flat thin blade. We so take the true hockey stick’s features for granted that any discussion of their necessity may seem unnecessary to some. That said, what is no-brainer stuff now was not always obvious. It is Thomas Raddall’s officers’ point of view that one must consider, and/or that of Canada’s colonists who thought that stick games on ice merely required their old country devices or sticks with curved or crooked ends.

So let’s review some basic information. The letter H in the illustration refers to a proper blade’s height. Sticks with blades that are too high, like a goalie stick, will prove useful for some defensive purposes. But for normal players – non-goalies – too much height will result in a net loss of benefits because ‘stick battles’ are typically won in tenths of seconds or less. Make the blade too low and you have the street hockey player’s nightmare: a device that cannot trap or sweep the puck-like object or ball with any authority. Proper length (L) is also necessary. Blades that are too long will prove as useless as overly high ones, for also being too cumbersome. Conversely, if the blade lacks sufficient length the user won’t be able to sweep the puck or ball in both directions, let alone at the seemingly unlimited speeds offered by proper blade length. If an end is not sufficiently thin (T) the user won’t be able to effectively stick-handle, sweep or trap – all of which require leaning the blade over the puck-like object. The proper stick’s flat base provides similar advantages; sticks with crooked or overly curved ends do not. Finally, flatness on both sides of the blade enables the user to pass and shoot with optimal precision and with superior accuracy over a range of desired elevations. These benefits are also eliminated or hindered whenever one uses sticks with rounded ends.

Nowhere is the ruthless simplicity of the true ice hockey stick’s “necessary” nature more on display than in a 5-on-3 power-play situation. The terror this situation inspires – in scenarios that truly matter to the so-incarcerated and their fans – has everything to do with the totality of what was just discussed in the previous paragraph. The flat thin blade fully explains the penalty killers’ extreme reluctance to break from their triangular defensive formation. Any such violation, they know, and fans know, will result in openings that the puck-carrier will immediately exploit because he has a stick with a ‘flat thin blade’. If the puck-carrier decides to retain possession he can easily sweep the puck away from the onrushing defender. The same features enable him to ‘protect’ the puck a second way, by sweeping it to multiple wide-open teammates. The defenders can only continue to rush until their legs feel like lead or until they gift one of their opponents with an uncontested shot.

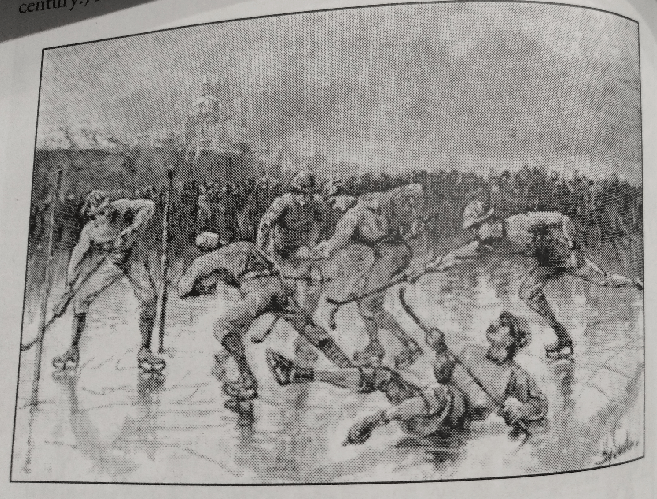

Next, have those on the power-play use hurleys, camans, field hockey sticks or sticks with merely curved or crooked ends and we have a very different outcome. Now no restraint is necessary on the three defenders’ part, even if they are using the same old country devices. They can and should charge the puck-carrier because his stick provides no meaningful deterrent. Once a defender arrives in his opponent’s vicinity (about one second after he decides to charge) the puck-carrier will be hard-pressed to defend the puck on his own. He will feel most fortunate if, after he tries hitting the puck to another teammate, it actually reaches its destination. Even if it does, the receiver will have trouble trapping the puck because he too lacks a flat thin blade. Before the puck even bounces off of his stick another defender will have charged with the same impunity as the first. The inevitable result of what I am describing will look pretty much like what one sees in the illustration below, taken from On the Origin of Hockey (2014), written by SIHR members Carl Gidén, Jean-Patrice Martel, and Patrick Houda: a clumsy and inferior pack game that is frankly unworthy of the title, ice hockey.

Based on what we know of their old country sticks, we can be quite certain that Raddall’s officers and Nova Scotia’s first settlers must have thought that a puck-like object was something to be chased and whacked at on ice. They would have been the ones with the “primitive” understanding, had the Mi’kmaq already learned of the flat thin blade’s necessary nature. The Mi’kmaq would have schooled the officers at the First Meeting of ca. 1749-61, by showing them what it means to control, protect and direct a puck-like object.

The flat thin blade made man the master of the puck-like object. It represents more than a set of necessary features. It is an evolutionary end-point that explains the eventual on-ice extinction of all “curved” and “crooked” sticks. This is not only proved by what we know from ice hockey. The same inevitable conclusion was reached in the sport of bandy. Once the flat thin blade was introduced, there really was and is no going back to ‘stick ball on ice.’

EVOLUTIONARY COMPARISONS ##

As mentioned, in traditional renderings of ice hockey history it is said or (more commonly) inferred that the ice hockey stick evolved exclusively from Britain’s old country sticks. The Mi’kmaq, for being characterized as hired help, are never given serious consideration as possible contributors to the same evolutionary process. Let’s do that now, by assuming for the sake of discussion that the Mi’kmaq did indeed invent the prototypical ice hockey stick (like the one shown in the sketch I presented earlier). Let’s further assume that they made this discovery prior to the arrival of the British in 1749. If this was true, our next question becomes, How might Britain’s old country devices have contributed to such an indigenous stick’s further evolution?

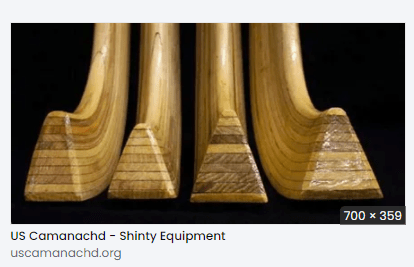

Crafted over thousands of years, the Irish hurley is our first contender. Several are seen in the next image. Surely none would argue that these sticks aren’t highly ideal for their real purpose: carrying or juggling a ball and striking the same in mid-air. Clearly the hurley would provide some utility on flat surfaces, but only when other hurleys are involved. If the owner of such a stick wishes to compete on frozen settings with owners of sticks like the one seen in our sketch, his only practical option is to adapt his hurley in that direction. This is the antithesis of an evolutionary contribution.

In the next image one sees some modern caman sticks used for the Scottish game, shinty. Note the ends’ relative thickness and how the blades are angled, like two-sided golf clubs. Such angulation is superb for a game that is like running golf, where the primary objective is to hit a ball above the grass for distance. That said, all of the camans shown will prove to be useless on ice because their angled stick-ends can’t trap oncoming pucks. Stick-handling is also out of the question. If our caman owner wishes to compete on ice against players using prototypical ice hockey sticks, he must sand his stick end down so that it is thinner and has two flat sides. Again, no evolutionary contribution.

I did find images of older camans that may have flat versus angled sides online. It’s hard to tell because the photos don’t show side angles, as does the previous image. However, even if other camans did have flat sides this alone brings nothing to the evolutionary discussion because we are presuming that the Mi’kmaq had already introduced this feature prior to the arrival of colonial Canada’s first shinty player. Another practical problem is that all caman stick-ends lack the ice hockey stick blade’s required length. That’s because shinty involves hitting a ball. Ice hockey predominantly involves sweeping and is also less about going in straight directions as it is about turning in half-circles. The proper hockey stick’s blade length allows for constant control while turning. The caman’s uniformly short ends inhibit the same staple maneuvering.

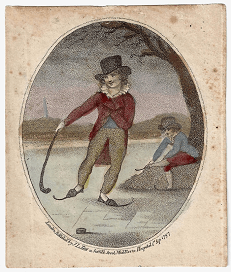

This leaves us with English “hockey” sticks. The earliest English evidence that we know of may still be the one that comes from a 1797 engraving that is featured on the cover of On the Origin of Hockey. An old image indeed. However, in this discussion we should point out that the engraving appeared forty to fifty winters after Thomas Raddall’s First Meeting in circa 1749.

The 1797 English stick seems to lack the proper ice hockey stick’s required thinness. At the very least, it cannot be said that the stick is sufficiently thin based on what one sees. The likelier thick end is well explained by the possibility that the same stick was used for field hockey in warmer months. There it is suitable, because a relatively thick end allows the ball to travel faster and farther on grass. It is not suitable on ice: If the 1797 stick’s end is just one inch thick it would be much too thick to trap or maintain control in competitive situations against players using flat thin blades. This leaves out the fact the 1797 stick’s end lacks a sufficiently flat base and may have rounded sides. Although old, it too brings nothing to the evolutionary discussion.

Most of the English sticks shown in On the Origins of Hockey are from well after 1797. They vary considerably in design and appear to have been used primarily for field hockey. Even though they are often from the mid-1800s – a full century after Raddall’s origin story – the SIHR authors’ recurring suggestion seems to be that these English devices somehow contributed to the ice hockey stick’s evolution in Canada. This kind of inferred approach mimics the traditional way of viewing the evolution of the ice hockey stick in another way that we haven’t yet considered. Both suggest an evolutionary dynamic that one-way in nature: England to Canada only in the English theory’s case; Britain to Canada only in the traditional narrative.

As far as English stick games played on ice go, the SIHR authors only introduce two other sticks that would precede James Creighton’s first order of Halifax “hockey” sticks for his friends in Montreal – the 1864 Windsor illustration and the 1797 engraving being the first two such examples we have seen. Those two other English sticks are presented below. On the far left of the three-part image one sees players on ice in London in 1855. I was unable to find the date of image on the far right, which is entitled Hockey on Ice, but frankly the dating doesn’t really matter because of our ongoing evolutionary question. As with the 1855 sticks seen on the left, none of the sticks seen in the Hockey on Ice image meet the prototypical ice hockey stick’s necessary requirements either.

What may be most telling about the two outside images above, and the 1864 one from Windsor, is how strongly all three suggest that many English players from the mid-19th century hadn’t really begun to consider the notion of how to best control, protect and direct a ball or puck-like object on ice. The players involved all seem to believe that a ball or puck-like object must be struck rather than swept. It would make sense that English ‘stick ball’ players would think such a thing, since England and Scotland are neighbours and as shinty is thought to be older than field hockey. Note how several these so-called English “ice hockey” players are emulating the modern shinty player’s movement in the central image. The same is true of at least one player in the 1864 Windsor, England image shown earlier, where the arrow in the upper-left corner points to such another clearly uninformed player.

Returning to our central question: None of the sticks shown in the three-part image would contribute anything to the evolutionary discussion either, if the Mi’kmaq had invented the prototypical ice hockey stick and its flat thin blade prior to the arrival of the British in 1749.

However, when we set aside our current terms of discussion, and with that the Mi’kmaq’s invention claim*, the authors of On the Origin of Hockey do introduce one English stick that could have affected the true hockey stick’s evolution, in theory. In order to properly introduce that stick I must go about things in a round-about way.

CANADA’S EARLY ICE HOCKEY STICK RECORD ##

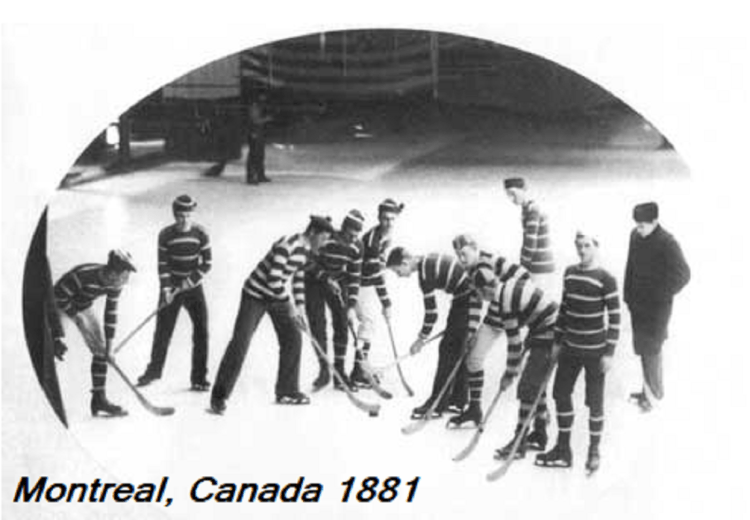

I will begin the next section by introducing the world’s oldest known ice hockey photograph. Taken in Montreal in 1881, the photo nearby shows players from McGill University. All of the sticks resemble the 1878 McCord stick, which makes a good deal of sense, since it is only three years later. A very interesting possibility is that these 1881 sticks may resemble those used in James Creighton’s famous demonstration match at the nearby Victoria Skating Rink on March 3, 1875. Some may have been used in that most historic game.

All of these 1881 sticks have the true hockey stick’s “necessary” elements as previously defined, for featuring reasonably well-proportioned, reasonably flat thin blades. A key thing to keep in mind here pertains to our evolutionary question. The sticks seen above represent proof that the flat thin blade had been introduced in Canada by at least 1881 – or rather 1878 (through the McCord stick) to be most specific.

Don’t be confused by the 1881 sticks’ slightly curved bottoms. What matters is that the bases of the blades are sufficiently flat and will therefore enable their users to trap and sweep effectively in all directions and accurately elevate the puck over a range of elevations. As for why these sticks have slightly curved bases, it should be kept in mind that we are still well within the age of experimentation in 1881. A few more decades would pass before the ice hockey stick’s blade attained the near-universal proportion that one sees today. My personal guess is that the curvature has something to do with the relatively short shafts, and that the designer opted for such curvature in order to better control pucks that were relatively close to the puck-carrier’s feet.

To our earlier discussion of Britain’s old country sticks, it seems quite obvious that the players in the 1881 photo would control the game, were they to play against teams who dared to challenge them with hurleys, camans or any of the English sticks we have seen so far. Here the rubber meets the proverbial ice. Doubters can easily test this prediction, as it would not be difficult to produce copies of the 1881 sticks and the British ones that we have seen so far.

The next Canadian photos come from nearly one decade later. These later sticks also all display our necessary features. Such replication complements the adage mentioned earlier: Once the flat thin blade is introduced, there really is no going back.

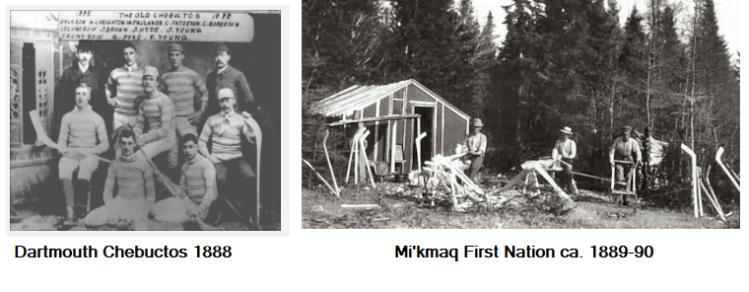

On the left one sees the Dartmouth Chebuctos, a Maritime dynasty club whose sticks might actually have been “crafted” by the Mi’kmaq stick-makers seen on the right-side image. The 1889 Chebuctos famously went to Quebec where they played some elite teams and lost decisively by an aggregate score of 23-3. I had long since presumed that this one-sided result was mainly due to the significant differences in population between Halifax-Dartmouth and Montreal or Quebec City. On second glance, the differing stick ends raise another intriguing possibility. Were the Quebec teams using flat thin blades that offered superior mobility and with that a significant advantage? Again, such a question can be very easily tested, but that is not our primary consideration. The main points are that the photos strengthen the flat thin blade legacy within 19th century Canada and that the Dartmouth club would have soundly defeated any team that challenged them with any of the British sticks seen thus far. Of course, all of the Mi’kmaq-crafted sticks seen on the right-side of the image above would offer the same necessary advantages. Perhaps the more telling thing in that second image is that those sticks all look the same – as is true in the Chebuctos’ photo and in the 1881 one from Montreal.

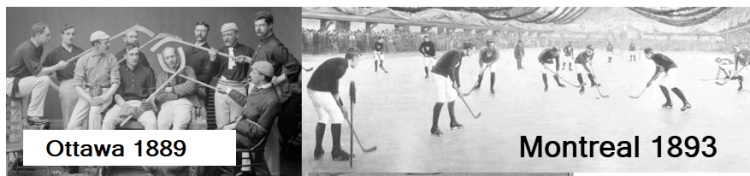

Likewise in the 1889 photo seen above, of Ottawa’s Rideau Rebels (where James Creighton sits third from the left), and of two elite teams that are seen playing at Montreal’s Victoria Skating Rink in 1893: Such recurring uniformity cannot be a coincidence. Perhaps teams ordered their sticks in batches during this era, based on the teams‘ preferred adaptations of the prototypical ice hockey stick.

In the next section we will turn to similar evidence that existed in present-day Canada prior to 1872. But before we do one more thing must be addressed, an artist’s depiction of an ice hockey match that was played at Montreal’s first Winter Carnival in 1883. The image below was apparently made by an artist who saw the game unfold, and all of the players’ stick ends lack the true hockey stick blade’s necessary features. All lack adequate height and are far too short, appearing to be about the same length as the players’ hands. How can that be, if our ‘adage’ is correct!?

To see why this must be a poor artistic representation of the sticks that were actually involved, we start with the fact that the 1883 tournament could not have been more closely contested. A total of four games were played in the tournament. Three of the matches ended in ties. The other concluded in a one-goal victory for the McGill team which won the 1883 tournament. Next we recall that the 1881 McGill players were using proper sticks just two years earlier. It would make no sense for the McGill team to trade all of their 1881 sticks for the functionally useless ones seen in the image above. Such a choice would amount to more than a step backwards in the evolutionary sense. It would be one giant leap in the wrong, counter-intuitive direction.

Any suggestion that the 1883 tournament’s two other teams ‘may’ have been accurately depicted is also undermined by the results. Had the McGill team used 1881 sticks while their two opponents used sticks that looked like the canes seen above, the results would not have been close. What happened instead is that McGill played the other teams to a draw and a one-goal victory – the Quebec club and the Montreal Victorias. Such even results suggest that all of the 1883 teams used very similar sticks, and likely ones that were identical or comparable to those seen in the 1881 photo.

Finally, it wouldn’t make the same sense to suggest that the same logic should be applied to all of the English stick illustrations seen thus far. The key difference is that they lack supporting evidence. The 1878 and 1881 Montreal sticks provide exactly that in the case of the illustration we are considering, earning reasonable doubt in the process. So do the later photos, by upholding the adage that there is not going back once the flat thin blade is introduced. The 1883 tournament’s manifest results show that the sticks seen in the image above must be very poor representations of the ones that were actually used. This may be because the 1883 tournament marked the first time that Montreal ice hockey took centre stage before a wider North American audience. We should not expect first-time viewers to immediately recognize the necessary nature of the reasonably well-proportioned, flat thin blade.

PRE-1872 CANADIANA ##

Next we look to the era that unfolded in ice hockey before James Creighton ordered “hockey” sticks for his Montreal friends in the 1872-73 era. Since Creighton moved from Halifax, Halifax is where those sticks had to have come from. Vital to our next discussion is the matter of Henry Joseph telling the Montreal Gazette that he had never seen “hockey” sticks in Montreal prior to this occasion. Another thing to keep in mind is that Joseph said this in 1943, when basically everyone in Canada knew exactly what an ice hockey stick looked like. This must mean that the sticks Creighton ordered were sufficiently similar to sticks of the 1940s which in turn means that they very likely had flat thin blades and were unlike Britain’s pre-1872 old country devices.

The picture Henry Joseph paints discreetly tells us another very important thing: A hockey stick market existed by 1872 in Halifax-Dartmouth, which happens to be exactly where the Mi’kmaq are known to have crafted many of early ice hockey’s sticks afterwards and for more than a half-century after Creighton’s first Montreal order.

In the photo above one sees a stick that Martin Jones shows in Hockey’s Home which he says was crafted in Nova Scotia in 1865. Such a stick’s main importance to this discussion would have to do with being crafted prior to James Creighton’s move. One result is that this chronologically supports Henry Joseph’s testimony. More discreetly it shows that the flat blade’s necessity had been recognized in Nova Scotia before 1872, while its “single piece” craftsmanship seems to complement what we know of the Mi’kmaq’s famous sticks*. Another thing to point out here is that any Nova Scotia stick is easily accounted for in Thomas Raddall’s indigenous-colonial claim which speaks of Mi’kmaq sticks being first distributed around Halifax-Dartmouth and later to other places which must include the same Canadian province.

Another person of great consequence in ice hockey’s pre-1872 discussion is Dr. John Patrick Martin. Raddall wrote the forward of the scholarly Dr. Martin’s most well-known work, The Story of Dartmouth. On page 74 of Hockey’s Home Jones tells us that in another work, Birthplace of Hockey, Dr. Martin reported that “organized [hockey] games played in [Halifax’s] new rink in the winter of 1863 were regularly reported in the local papers.” This also strengthens the notion of James Creighton ordering sticks from Halifax in 1872-73. Hockey games were played in Halifax’s new barn, which opened in 1863, because a hockey stick market already existed there.

Likewise, on page 54 Jones writes that “advertisements touting ‘strong and accurate’ Rex and MicMac hockey sticks appeared in the newspapers commencing in the 1860s.” I was unable to determine the primary source of this very important commentary. Dr. Martin seems like an excellent candidate, given what we just learned about his attention to Halifax newspapers. However, Jones attributed the footnotes that preceded and followed this line to the widely respected Bill Fitsell, founder of the SIHR. Based on what we know of both individuals, the rest of us can be certain, beyond a reasonable doubt, that Halifax papers from the 1860s did indeed regularly report on indoor hockey games and had ads featuring hockey sticks. After all, surely none would suggest that either man lacked the ability to read and understand newspaper articles and advertisements, or that they lacked the character to report such findings accurately and honestly. Henry Joseph’s testimony is once again supported by direct linking evidence: the literate Creighton ordered Montreal’s first ice hockey sticks because a stick market existed in the Halifax area since at least the 1860s.

Or much earlier… On page 44 Jones displays a silhouette image of a boy holding what appears to be a hockey stick over his shoulder. Seen nearby, my one concern is that the otherwise proper-looking blade looks a bit low. While it may lack the proper height for trapping and effective sweeping, it also a fact such determinations come down to the relative size of the puck-like object. I tend to think that the blade does indeed have proper height because the thorough Jones was able to reproduce a highly accurate shadow image of the silhouette by using what he calls an “antique” stick. In such a test, conducted in this case with the assistance of Stephen Coutts of the Nova Scotia Sports Hall of Fame, the age of the testing device is irrelevant. Only the antique blade’s true proportions matter. Jones’ and Coutts’ test results legitimize the possibility that proper sticks were in use in Halifax by 1830-31 and two decades prior to the birth of the so-called “father or ice hockey,” James Creighton (on June 12, 1850).

TWO-WAY MIGRATION THEORY ##

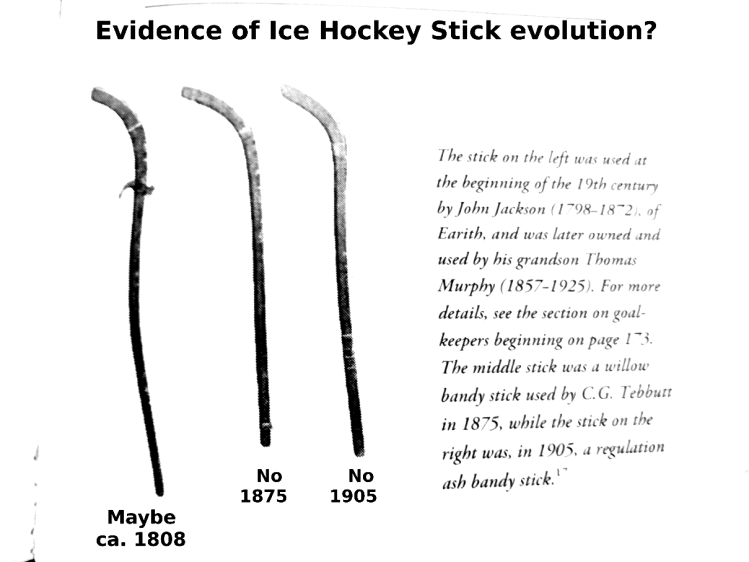

Our now-concluded “round-about” tour was necessary in order to properly present the one English stick that the authors of On the Origin of Hockey provide which may have influenced the shape of the prototypical ice hockey stick. Seen in the image below, I emphasize ‘may’ because this one stick offers is a theoretical possibility only. In order to embrace that possibility one must set aside two things: the Mi’kmaq First Nation’s claim* that they invented prototypical stick prior to the founding of Halifax in 1749 and the Western thinker’s preference for linking evidence. This one candidate stick is shown on page 171 where the authors seem to only infer that it and the two others to its right somehow contributed to the ice hockey stick’s evolution. Now that our tour is over, one can more easily see why the other two sticks must be dismissed as evolutionary contributors.

The 1905 stick on the far right must be dismissed because, as we have seen, by this time the proper hockey stick and its flat thin blade had long since been introduced in Canada. The 1875 English stick in the middle has also failed to earn its way into the evolutionary discussion, for having been crafted after the introduction of ice hockey sticks in Montreal by at least two years and longer when Halifax’s 1830-31 silhouette and pre-1872 hockey stick market are considered. Chronologically speaking – that being an essential consideration in any evolutionary discussion the only theoretical contender is the stick on the far left.

The Jackson stick‘s blade features all of the proper hockey stick’s five necessary requirements. It was owned an Englishman named John Jackson, of Earith, England, who lived from 1798 to 1872. Going forward, I will assume that this one contender was crafted when its owner was ten which would mean that it came into existence in 1808. Such dating allows for a significant theoretical possibility: Starting in 1808, any Englishman could have borrowed Jackson stick’s design and brought such a stick across the Atlantic, inspiring every proper Canadian stick that was crafted from 1808 onward. Such a reckoning would account for every Canadian stick we have mentioned so far, in theory, starting with the 1830-31 silhouette.

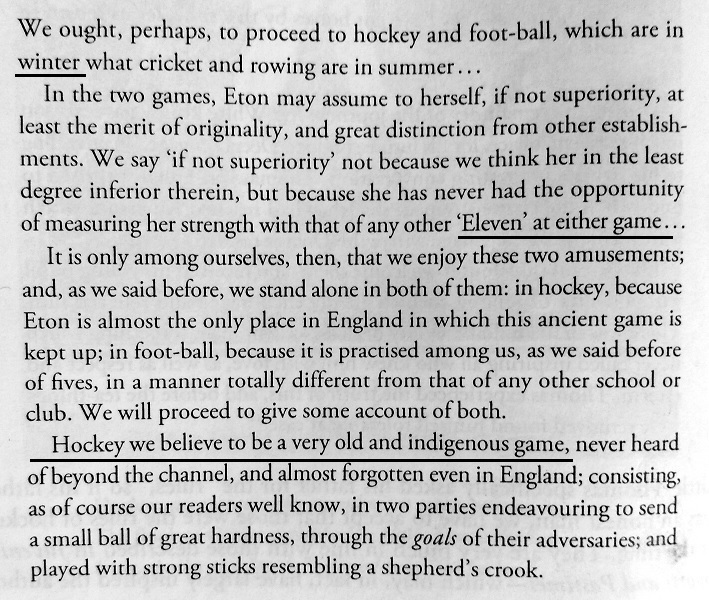

Within England the Jackson stick’s prototype may found its way to Eton College, which Frederick Arthur Stanley attended. On page 169 of On the Origin of Hockey the authors mention one Alfred Guy Kingan L’ Estrange, whom they credit with writing the following words to the Eton College Chronicle in 1911. Speaking of his own time at Eton, in 1846-1851, L’Estrange is quoted as saying: “The blades of the sticks we used were not curved, but lay straight on the ground at right angles to the hand and were about a foot long.”

To this the SIHR authors comment, “The concept of a hockey stick whose blade lies flat on the ground, rather than being curved, seems quite quite revolutionary for the early 1850s.” Then, after noting that L’Estrange apparently meant that such flat-based sticks were used for field hockey, and much their credit, they reasonably ask if such a stick would have been used for hockey on ice. They answer this highly likely scenario in the affirmative, by next citing an 1849 British source, The Boy’s Own Book, where those playing hockey on ice use sticks whose “end lies flat on the ground.”

It certainly isn’t difficult to envision the Jackson stick’s prototype finding its way to Eton from Earith at some point after 1808, over a decades-long period that would precede L’Estrange’s matriculation. Once there, its proper blade may have inspired officers and soldiers alike. Some Eton alums may have later brought copies of such sticks across the Atlantic to colonial Canada.

Because Thomas Raddall mentions “officers” the likelihood of such a scenario increases when one considers similar schools. Jackson’s hometown, for instance, is less than twenty miles from another venerated English institution that likely produced British officers in the 18th and 19th centuries, Cambridge University. How many such English schools are there to consider? How many 18th and 19th century officers are known to have attended such elite schools? This is another case where military historians may be able to refine our understanding of a related subtopic.

Plausible, but the even subtler fact is that the SIHR authors are only considering an England-to-colonial Canada stick migration theory. Seen in this light, the so-called English invention theory looks like an extension of the traditional theory’s one-way bias. On pages 98-99 of On the Origin of Hockey a passage is attributed to another an Eton alum named George William Lyttelton, the 4th Baron of Lyttelton. This “Baron George” was the eldest son of William Henry Lyttelton, the 3rd Baron Lyttelton, and Lady Sarah Spencer, daughter of the 2nd Earl of Spencer, George John Spencer. We are told that Alfred Guy L’Estrange reported that the Baron George had the following excerpt published in The Eton College Magazine in 1832.

The belief at Eton that hockey is a very old and indigenous game can only mean that the story of such a game had been circulation at Eton well before 1832. How did such a story get there? Clearly not from continental Europe, as this must be the place “beyond the channel.” To approach this mystery one must ask how many indigenous cultures the British military encountered from the start of their colonial era around 1500 – in places that got cold enough in winter to play a hockey-like stick game on ice. One such setting would definitely be colonial Canada. This line of inquiry doesn’t seem to matter at all to the authors of On the Origin of Hockey :

In fairness, the whole of their work indicates that the authors seem to believe that this “indigenous” commentary can be dismissed because they have shown, and shown very well, that the 18th and 19th century English had been playing stick ball games on ice in various places. However, by dismissing indigenous testimony they reveal how one-sided the English invention theory is at its core. [See Footnote here]

As mentioned, this approach mimics the traditional treatment of the ice hockey stick’s evolution which, in doing so, also removes the Mi’kmaq from the larger Canadian discussion as potential creators. Baron George’s Eton testimony compels one to also consider a colonial Canada-to-England migration whereby the Mi’kmaq may have influenced ice games played on the other side of the Atlantic.

Under the second definition of necessary, Raddall’s officers brought back famously “strong” Mi’kmaq sticks (with their flat bases) back to Eton and similar institutions for two reasons. In the first place, the officers he describes would have been especially inclined to resume playing stick games on ice upon their return to Britain, since that’s what they did in colonial Canada. Secondly, they would have known that Mi’kmaq sticks were especially useful for such activities. The practice of taking Mi’kmaq sticks back to Britain and places like Eton could have been going on with some regularity for up to seventy to eighty years (since 1749-1761), easily accounting for what have been a very old indigenous story at Eton by 1832.

Let me be the first to point out that the things just mentioned prove nothing. However, they do show that it makes no sense to presume that any cross-Atlantic migratory effect must have been exclusively one-way. As far as the hockey stick’s evolution is concerned, a Canada-to-England migration may be the better of the two possibilities. Such a scenario could have begun by up to fifty to sixty years before the birth of an 1808 stick – plenty of time for a Mi’kmaq prototype to have inspired John Jackson’s English device. In the England-to-Canada way of thinking we must imagine Jackson having similar links to Eton. In the Canada-to-England way of thinking we know of such a strong connection, and of an old indigenous story that provides something well beyond imaginary considerations.

Of course, it is entirely possible that ice hockey and bandy sticks emerged from with their own respective domains, without any cross-Atlantic contributions. However, unless historians know otherwise, no theoretical construction of bandy history should be considered adequate unless the Mi’kmaq are mentioned as possible contributors to the bandy stick’s design.

A Mi’kmaq stick may well have inspired the so-called “father” of bandy, Charles Goodwin Tebbutt. He was the son of a land-owner who came from Bluntisham, only twenty miles from Cambridge. Born in 1860, the obviously literate Tebbutt grew up during a period when around half of England was illiterate. He is not only credited with publishing the first rules of bandy but also other books, and had the apparent means to spread the game to northern Europe, Sweden, Norway and Denmark. All of this infers privilege during an era when privileged individuals were especially likely to gather in exclusive circles. Since he was born a full century after Raddall’s First Meeting, and three decades after the Baron George’s Eton account, one should not be surprised if Tebbutt discovered the Mi’kmaq’s prototypical stick by way of an Eton or Cambridge student/alum. Nor should one be surprised if Tebutt shared the same revelation with his affluent peers at Oxford, another Eton-like institution where the first bandy match is said to have been played.

RECENT CANADIAN DISCOVERIES SINCE 2015 ##

In Thomas Raddall’s claim the gospel of the flat thin blade began in the mid-1700s… spreading very slowly from the lakes of Dartmouth. More than a hundred years would pass before the prototypical ice hockey stick found its way to a place that had the necessary glitz to kick the same stick diaspora into overdrive. Raddall’s claim discreetly proposes that two kinds of sticks were crafted prior to 1872: Mi’kmaq crafted sticks and others made by colonists. All pre-1872 sticks should be considered with this distinction in mind.

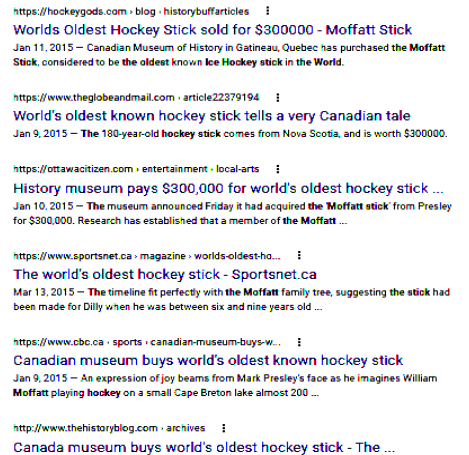

The Moffatt stick appeared after the publication of On the Origin of Hockey, and about a decade and a half after the SIHR concluded that ice hockey was played with ‘curved’ sticks. Since it was crafted in 1835-38, the Canadian press declared the Moffatt stick (seen in an image taken from the Ottawa Sun) to be the “world’s oldest known ice hockey stick” or some variation thereof. In doing so the national media revealed how dominant thinking can condition the general public to consider something one way and overlook other possibilities at the same time.

The far more fascinating and very real possibility is that the Moffatt stick was used, not only for Nova Scotia ice hockey, but also for the Mi’kmaq’s stick game, Oochamkunutk!!The Mi’kmaq didn’t abruptly quit their ice game in the moment when Raddall’s officers decided to separate and begin playing their adapted game, Alchamadijik – or that which would go on to claim the title of ice hockey. There must have been a time when both games were played, as indicated by the grey box in the image below. From this it becomes entirely possible that the original colonial owner of the Moffatt stick traded some indigenous Oochamkunutk player for what originally was an Oochamkunutk stick! Raddall’s officers certainly did such trading in the beginning of their partnership with the Mi’kmaq. It would have taken some time before they and others began hiring the Mi’kmaq to “craft” such sticks from scratch.

The Moffatt stick would be very useful in a game that requires the effective controlling, protecting and directing of a puck-like object. What we know suggests that this was also primary objective in Oochamkunutk – this earlier game played on ice with sticks, a puck-like object and goals. No matter who made it, and for which game, the Moffatt stick’s design can only mean that its maker knew well of the flat thin blade’s necessary nature. It also fits the Raddallian profile for having been crafted in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia – home to both a military outpost and a Mi’kmaq settlement*.

However, because we must continue to consider theoretical evolutionary influences I must emphasize that the 1835-38 Moffatt stick is still considerably younger than the stick owned by the Englishman, John Jackson. An 1808-crafted blade would have nearly thirty years to cross to reach Cape Breton from England and inspire the Moffatt design.

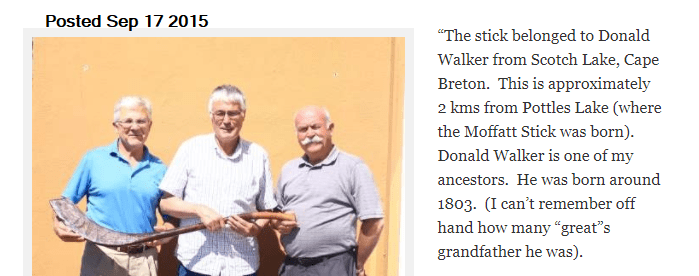

Next we consider the less well-known Walker stick which seems to have reached public attention just months after the Moffatt stick made headlines. Seen in the next image taken from birthplaceofhockey.com, the accompanying article reports that the Walker stick is owned by one James Jessome. Remarkably, given the potential magnitude of our current discussion, the Walker stick is said to have been crafted “where the Moffatt stick was born”, near Pottles Lake in Cape Breton (and therefore also well within Thomas Raddall’s domain).

The Walker stick has the initials DW carved into it and is said to have been owned by a Donald Walker who was born in 1803. When we apply the same standard that we used with John Jackson’s stick, the Walker stick is seen to have been crafted in 1813, when this Donald Walker was ten. Now the evolutionary gap has closed considerably. At 1808 versus 1813, the Jackson prototype now has only five theoretical years to influence the Walker stick.

However, a second source quotes the Walker stick’s current owner as saying, “My people landed in Scotch Lake (near George’s River, Cape Breton) about 200 years ago… Donald Walker was the original owner of the hockey stick.” According to Jessome, three Walker family members had that name since 1803… Although he seems to say otherwise, we should at least acknowledge the possibility that the DW initials may refer a DW who was born one or two generations after the original Donald Walker of 1803. At twenty-five years per generation, it would follow that the Walker stick may have been crafted as late as 1863 (when the youngest DW was ten).

I would suggest that the much more important observation is how very similar the Walker and Moffatt sticks are in design, proportion and quality of craftsmanship. No matter which is younger, their common pedigree provides direct evidence of standardization. Together they tell us that some people around Cape Breton had learned that there is no going back once the flat thin blade is introduced. In this context they speak to our own continuing demand for such necessary sticks.

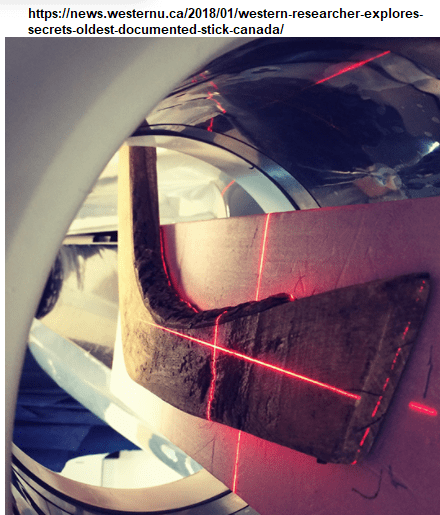

Finally, I present the latest recent discovery that I know of, and the oldest stick shown so far. The Laval stick was introduced more than two years after the Walker stick, and given its name for being studied at Laval University in Quebec. Here I should mention that Canada’s largest province includes large swaths of Mi’kmagi First Nations territory.

In a January 2018 article the CBC told the nation that “what’s believed to be Canada’s oldest hockey stick” was carbon dated to 1770, plus or minus 20 years. [This italic and the next italic are mine.] That would mean that the Laval stick could have been crafted as late as 1790, preceding the birth of John Jackson by eight years and the 1808 dating of his English stick by nearly twenty years. It also could have been crafted as early as 1750, preceding the Jackson stick by nearly sixty years. However, in another article from where the nearby image was taken, we are told that the “the oldest hockey stick known to exist” was instead dated to 1776 plus or minus 20 years. In this scenario the Laval stick still precedes the birth of our English friend by two years, at the latest. Chronologically speaking, there is still no way that John Jackson’s English stick could have influenced the Laval stick.

All three of these newly-discovered sticks have proper blades, yet there are differences in the overall shape of the Laval stick and the Moffatt and Walker ones. This is easily explained through our own behaviour. We have seen that differentiation in stick design occurred for several decades beyond the birth of Canada in 1867 (during which time the “necessary” blade was always preserved). If that outcome should be expected – because in the late 1800s people were much more separated than they are today – we must expect the same to be true of earlier times.

In the picture above one sees a positively Raddallian presentation of the Laval stick as featured on its owner’s Twitter site. Take a good look. If it seems familiar, that’s likely because I traced the same stick in that sketch I presented earlier. Much of the comparing in this essay has been done with this, Canada’s current oldest ‘Ice Hockey-Oochamkunutk stick‘, in mind.

If Thomas Raddall’s officers saw the Mi’kmaq using sticks like the one above, what they saw on ice would have surely been a revelation – to them – given what we know of Britain’s 18th century sticks. It is easy to see why the officers would have seen such a stick as necessary in the practical-recreational sense. The Laval stick offers that which draws the hockey person repeatedly to frozen lakes, arenas, streets and gymnasium floors. It would provide far greater on-ice satisfaction compared to old country sticks, the potential for ever-increasing levels of mastery of the puck-like object and decisive competitive advantages over those using hurleys, camans and ‘curved’ or ‘crooked’ field hockey sticks.