This essay combines two earlier essays that I posted on this website on September 30, 2023. Special thanks to Marcel Lang and James Shand for helping with that presentation. What follows is the second essay in my book, The Four Stars of Early Ice Hockey. Mark Grant, 2024

In this essay, we discuss Ice Hockey’s birth and earliest evolution up to the end of the 19th century. This is a one-person project, brought to you by a ‘yours truly’ who sometimes refers to himself in the plural. We use Capital Letters to refer to the sport in general here. Our “Ice Hockey” includes all variations of the modern game. For more specific versions of “Ice Hockey,” we use phrases like “Montreal ice hockey,” NHL ice hockey, women’s, junior and Olympic ice hockey, and so on.

Searching for an asterisk * to jump from section to section.

* INTRODUCING “HALIFAX”

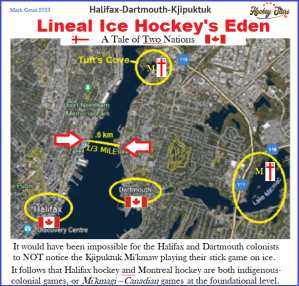

In recognizing “Halifax” as the second Star of the sport of Ice Hockey, we refer to the settlers of Halifax and Dartmouth.

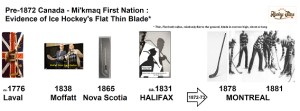

We present our Stars in order of their known appearance only, with no regard to how stars are usually awarded in Ice Hockey. Our first Star were the Mi’kmaq First Nation members who lived in the same area, which they called Kjipuktuk. We shall refer to them as the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw.

This essay is less about the second Star, in particular, and more about the partnership that the second Star formed with the first. We discuss Halifax and Dartmouth in isolation when the time is right. For the most part, we treat the first two Stars together, as the “partners” who built “Halifax ice hockey” and, with that, the earliest foundation of what would become “Canada’s Game.”

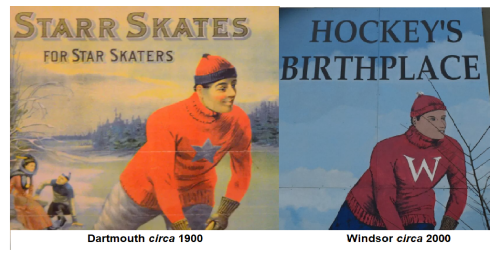

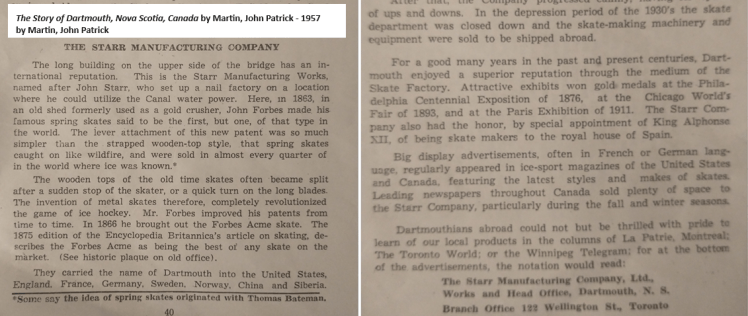

In the true story of Ice Hockey history, Montreal is indeed the Rock Star of the 19th century. By the same analogy, Halifax must have been Roadies par excellence. Montreal ice hockey grabbed all of the glory in real Ice Hockey’s earliest tours of Canada. But that game was predicated on our first two Stars’ technologies and those who worked ceaselessly behind the scenes, in Halifax-Dartmouth, feeding a young nation’s insatiable demand for their sticks and their skates.

Think of Halifax as the engine that drove Montreal’s conquest of Canada’s frozen waters. Halifax remained extremely involved after the 1872-73 Halifax-to-Montreal transfer. Both communities played leading roles in setting up one of Canada’s greatest cultural pillars. So great was the nationwide demand for our partners’ gear that Halifax’s integral role in Montreal’s success has become lost to the general public. It has been buried by that greatest form of flattery: mass imitation.

At the end of the day, all of today’s leading theories and claims must answer what we know about Ice Hockey’s original partners. Most fail, because they don’t seriously consider Ice Hockey’s first two Stars. Depending on who is involved, one can might say they fail epically.

* TODAY’S HOCKEY HISTORY ZEITGEIST

In the current 2024 era, there seems to be a major disconnect between what we actually know about Ice Hockey history and what the general public believes. The latter refers to today’s zeitgeist or common ways of thinking about ice Hockey history.

We note, going forward, that our understanding of today’s zeitgeist may differ from the reader’s. Having said that, in our own survey of Ice Hockey history, we find that there’s much mixed messaging regarding how the sport was born and how it evolved until the end of the 19th century.

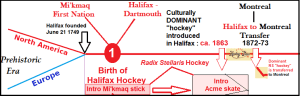

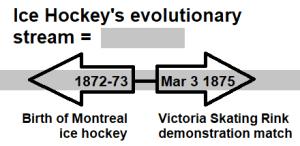

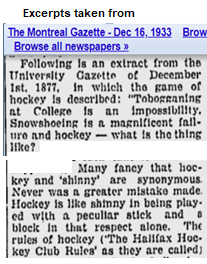

We find that many of today’s popular conclusions about Ice Hockey history come from two core ideas. Both been around for quite some time. We can date the first core idea to as early as 1899: all forms of “hockey” that preceded Montreal are treated as the same and are very loosely described as backward games devoid of rules. The second core idea had been at least several decades in the making. It suggests that Ice Hockey was somehow born in Montreal in 1875, two years after we know Halifax ice hockey was introduced there in 1872 or 1873.

A host of culturally dominant fictions have arisen from these two core ideas, which get repeated and repeated owing to their search engine rank. Most are very easily exposed as false when considered in relation to a real-life episode that we call the Halifax-to-Montreal transfer.

Unfortunately, if you’re like us, you won’t find any word about this episode near the top of the search engines. And isn’t that odd, since we are talking about the literal birth of Montreal ice hockey? Instead, at the top of today’s search engines, you will be far more likely to find claims that the Halifax-to-Montreal transfer directly contradicts. Some say that Ice Hockey was somehow born in 1875, for example, or that the first organized game was played then—in Montreal, at the old Victoria Skating Rink (VSR). Various other claims rely on this historical treatment, leading to a plethora of claims that dominate today’s zeitgeist and amount to what I call the “VSR mythologies.”

Here, then, is something that the casual reader should know: many of the labels one reads about Ice Hockey history turn out to be figurative in nature. Ice Hockey is famous for its “codes,” and this seems to be one of them. Figurative usage is common in the ‘hockey history’ space. It may be the rule rather than the exception. No informed historian would ever say that Ice Hockey was literally born at the VSR or in 1875. Of course not! Non-historians do not know this, however, and they are left to crack the code. Most don’t, of course, and many casual readers are led to conclude that Ice Hockey was literally born in Montreal. This goes a very long way toward explaining how today’s VSR mythologies are sustained.

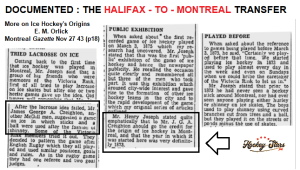

Suffice it to say that there are many reasons why we know about the earlier and decisive Halifax-to-Montreal transfer. The casual reader needs only to know one such piece of evidence. This essay’s first must-know article appeared in the November 27th, 1943, edition of the Montreal Gazette newspaper. In the article, Henry Joseph describes the literal birth of Montreal ice hockey and what led to it. One could not ask for a better primary source since what follows are the words of a literal eyewitness participant to what is arguably the least discussed, least considered episode in all of Ice Hockey history.

This passage is of defining importance to real Ice Hockey history. Henry Joseph’s testimony makes all of the 1875 VSR mythologies into a metaphorical Gordian Knot. It does so, because our eyewitness literally undercuts the central root fiction in which Ice Hockey is said to have been born two years after Montreal’s actual and literal introduction.

* HALIFAX’S LINEAL DISTINCTION * THE BIRTH OF ICE HOCKEY IN MONTREAL

* HALIFAX’S LINEAL DISTINCTION * THE BIRTH OF ICE HOCKEY IN MONTREAL

Henry Joseph told the Gazette that he and his chums had first tried playing lacrosse on skates, with “hectic” results. After that didn’t work out, he said that a McGill man, James Creighton, suggested that the group try another stick game, which Joseph very significantly likened to shinney. By then, around 1943, “shinney” had long since become a common way of referring to pond hockey in Canada. Joseph provides an excellent general description of the activity involved—a game involving teams, sticks, goals, and a puck-like object. Halifax ice hockey was already like field hockey before it got transferred to Halifax, in other words, as well as Irish, Scottish, and Mi’kmagi stick games.

One caveat before we go further: Our eyewitness said that Montreal ice hockey was “definitely” born in 1873. However, we seem to recall another occasion where Henry Joseph said that the same episode took place in 1872. That’s why we say that Montreal ice hockey was born in the 1872–73 period. On to the main event…

Henry Joseph doesn’t say a lot about what took place when Montreal ice hockey was literally born. Some of what he does say, however, allows us to confidently infer things that likely took place. For starters, our eyewitness said that his crew only hacked the Victoria Skating Rink on “some” Sundays. When all days of the week are treated equally, this means that there’s already a 6-in-7 (or 86 percent) likelihood that Montreal ice hockey was born outdoors. The chances for a VSR introduction lower further when the earlier lacrosse experiment is considered. Trying Creighton’s shinney-like game outdoors may have seemed like the wiser choice. Why risk inviting the ire of VSR management over another stick game that the group might also not like?

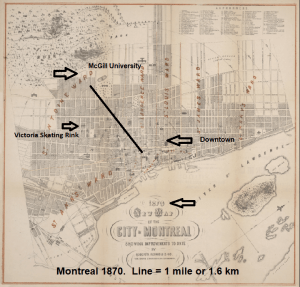

All signs point to the literal birth of Montreal occurring in this area shown in this map, outside and very likely within walking distance of the VSR, downtown, and the McGill University campus. Where the left-side arrows are.

There is also a very decent chance that it took place at the present location of the Montreal Forum, one of 20th-century Ice Hockey’s most storied arenas. The Forum was built over an outdoor pond where icons like Art Ross, Lester and Frank Patrick used to play as early as the 1880s. All we need is for that pond to be a hangout spot for ten years prior to then, to 1872–73, and there’s an excellent chance that the Forum site is the literal birthplace of Montreal ice hockey. Maybe one day someone will find something that confirms this indirectly—that this “Forum Pond” was likely in use on the day that Mr. Joseph describes.

Here’s something that we can safely infer: After the Montrealers had all laced up and obtained their very first Mi’kmaq sticks, there would have come a time when the others deferred to James Creighton to see what the group was supposed to do next.

We can be sure of this because we know that Creighton made himself the centre of attention following the failed lacrosse experiment. After they agreed to his suggestion, everybody had to wait for the arrival of his Halifax sticks. Of course, the others deferred to Creighton. How else could the Montrealers be expected to start playing a game that they had never played before? It seems unreasonable to think that the Montrealers may have even begun playing ice hockey without Creighton’s initial guidance. The others had never used a real Ice Hockey stick until that day. Our son of Halifax had played for all of his life.

We can also safely infer that Creighton had anticipated this moment. When the time came, he may have only said a few words. He may have spoken at some length. Either way, there must have been some explanation on James Creighton’s part. What must have happened after he was done becomes one of the most defining points in all of Ice Hockey history.

The Montrealers followed James Creighton’s lead.

In that moment, Halifax, Nova Scotia, attained immortal status in the history of Ice Hockey, because of what Montreal ice hockey would go on to become in the 19th century’s three remaining decades. Montreal’s success became Halifax’s success, and their great continued successes went on well past the time of this Halifax-to-Montreal transfer.

The moment is what secures Halifax’s great lineal distinction, among other things. Only Halifax hockey was transferred to Montreal, to the exclusion of all other “hockey” or hockey-like games that were played during that era. We alluded to why this is necessary to say, owing to the strength of the first core idea in today’s world, where Halifax ice hockey gets equated with literally all other versions of pre-Montreal ice hockey, and then lost to the zeitgeist for not being worthy of special mention.

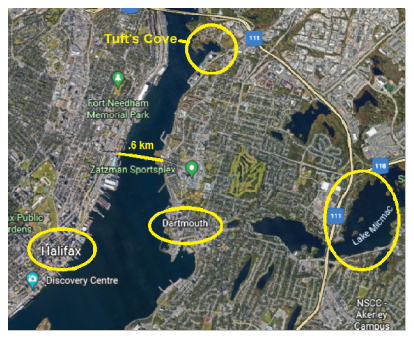

Despite our opinions of Halifax, Halifax’s lineal distinction must stand regardless of how evolved or underdeveloped it was at the time of the Montreal transfer. All that matters, in the lineal sense, is that we can identify the particular “hockey” game that Montreal inherited. Knowing this enables us to extend the line of history very precisely, beyond Montreal, to this five-by-four mile area. This is Ice Hockey’s literal Eden.

* DEFINING “HALIFAX”

Most people call this place Halifax, as we will generally. We will also sometimes call it Halifax-Dartmouth-Kjipuktuk, as a reminder that the Halifax partnership also included the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw and the Dartmouth settlers.

Here’s what happened, in a nutshell: After being born in Halifax, literally, ‘the stick game that became Ice Hockey’ was transferred to Montreal, where it hit the big time in twenty years and became Canada’s culturally dominant version of “hockey” played on ice.

This conquest happened during a time when others played “hockey” in other places. Through the 1872–73 Halifax–Montreal transfer, all of those games became non-lineal background performers in an epic 19th-century story that co-stars Halifax and Montreal. Their histories must not be equated with the singular one that was forged by the 19th century’s two main actors, who worked together to produce the version of “hockey” that secured Canada’s official definition of “Ice Hockey” in the early 1890s.

Another major consideration is the uniqueness of Halifax ice hockey. It’s hybrid character, as an indigenous-colonial game, falsifies another much more settled theory about early Ice Hockey history.

In what we called the “Traditional” theory, Ice Hockey is said to have evolved from three British stick games, each played on grass: Irish hurling, Scottish shinty, and English field hockey. It’s an excellent theory in general, but what its durability mostly proves is ironic. It tells us how superficially we continue to treat Halifax in these discussions.

This will be obvious to anyone who looks at or thinks about 19th-century Halifax. There, the Mi’kmaq stick game must also be accounted for. Therefore, all suggestions that Ice Hockey evolved from (only) three British games are like saying that the cardinal directions are North, South and West.

Seriously, how did we get to the point where Halifax-Dartmouth-Kjipuktuk is so easily missed? In the next essay, we will show that some historical errors can be traced back to the 19th century. For now, however, we note that the first national conversation about Ice Hockey’s origins seems to have begun in the middle of the 20th century.

* ICE HOCKEY’S mid-20th CENTURY ‘CIVIC’ DEBATE

By the early 1940s, Ice Hockey had become Canada’s favourite pastime. Fans listened to NHL games from coast to coast. They went to movie theaters to watch the highlights. This was the era when people started talking about building a Hockey Hall of Fame.

There was some expectation that the Hall would be built in the community where Ice Hockey was born. So, where did that happen? Three civic birthplace contenders emerged: Kingston, Halifax, and Montreal. Many of the articles we present here are from this period.

In the end, the birthplace debate turned out to be somewhat irrelevant, in that the Hall got parked in downtown Toronto in 1961. This, only after the Hall’s executives had earlier endorsed Kingston whose birthplace claim was later falsified.

Only Halifax and Montreal remained in Ice Hockey’s birthplace debate, which seems to have receded to the background. Keep in mind, that this retreat occurred during a lengthy, decades-long pre-Internet era when it was much more difficult to properly vet claims and evidence. Far more pre-digital Canadians had access to Montreal newspapers compared to those in Halifax. In the long run, we must not be surprised that the prevailing “dominant” interpretations would reflect this imbalance, at Halifax’s expense and in terms that favoured Montreal.

That seems to be what exactly happened. At some point, the Montreal theories began taking over the zeitgeist, then the search engines. The Victoria Skating Rink’s March 3, 1875 match gained such disproportionate favour that nowadays, in 2024, it literally eclipses all that took place in Montreal ice hockey earlier, in today’s ‘dominant’ lines of historical discussion. Or, maybe others have found at least one serious discussion about the earlier 1872–73 birth of hockey in Montreal.

In today’s world, therefore, it can be very helpful to know that hockey historians usually don’t mean that ice hockey was born in Montreal when they say such things. Figurative wordplay seems to be very common in this space, and no real historian will say that James Creighton is the literal father of Ice Hockey either. Nor would they say that the VSR hosted Ice Hockey’s first organized game in 1875. If asked, they will advise that these terms are to be understood figuratively. Of course, most people don’t ask. And so some will believe that these things are literally true.

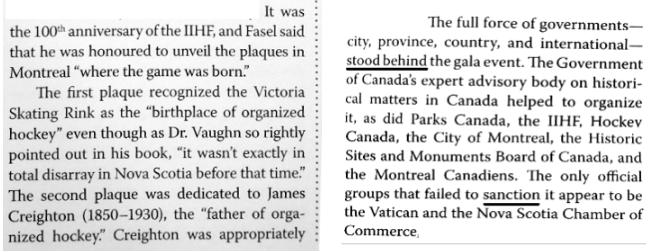

* DIGRESSION: ON ECLIPSES, PLAQUES AND PARKADESDecades in the making, this figurative treatment we speak of attained semi-official status in 2008. That was when René Fasel, the then-leader of Ice Hockey’s international organization, the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF), called Montreal’s Victoria Skating Rink the birthplace of organized hockey and James Creighton, the father of organized Ice Hockey.

This highly publicized event was part of the IIHF’s 100th anniversary celebration. I have decidedly mixed feelings about it. However, I firmly believe that the pros are much more important than what I see as cons. On that note, let’s revisit the neighbourhood where this went down, nearly sixteen years later.

In April 2024, just as I was finishing up my final essay for this project, my wife and I went to Montreal to see the total solar eclipse. Our first full day was Saturday, and, wouldn’t you know it!, Montreal was hosting Toronto in a Hockey Night in Canada game. Lots of people in red and blue jerseys walked around town.

In mid-afternoon, I found my way to the Autoparc Stanley. There was a moment, for yours truly, since I chose to hang flags at the VSR. The bricks-and-mortar parkade was on the very ground where the Victoria Skating Rink once stood. With the Canadiens’ arena just a few blocks away, various Montreal and Toronto fans walked on by. I asked some if they knew they were walking by what many historians would call the most important venue in 19th-century Ice Hockey history.

Nobody had a clue. So, I gave them a few details. Everyone who heard seemed quite blown away. This was hardly surprising, since these were all straight-up hockey people…

The Leafs-Habs game was underway when we strolled to the Forum which was surely one of 20th-century Ice Hockey’s most storied cathedrals. I would later learn that we had arrived on the 98th anniversary of the Forum’s first Stanley Cup final, when that team that used to play so near my elementary school became the last non-NHL team to play for the Stanley Cup. Those Victoria Cougars were coached by Lester Patrick, who used to play on the pond over which the Montreal Forum stands. Quite the location, this place.

On the Atwater side of the Forum I saw a giant Canadiens logo on the street. Surrounding the logo were spaces commemorating all 24 of this glorious franchise’s Stanley Cups, the most by far in NHL history. I would say “plaques,” but five or six of them were gone. In assuming that this took place some time ago, which may be wrong, those missing plaque’s absence made the whole presentation look jaded and uncared for.

I entered the Forum, half-expecting that I would have no problem finding those other plaques—the two that the president of International Ice Hockey had presented. I looked for a few minutes without success. And reminded that the Forum’s interior, although renovated, remains a very large space. I wound up asking the nearest employee.

“Those got removed a long time ago,” he answered quickly. “We get asked this all the time.”

How about that!?The IIHF’s plaques both got totally eclipsed… inside the Montreal Forum!

“You might want to check out the hallway where all of the Montreal Canadiens’ championship photos are,” said the employee, pointing the way. “It’s over there.”

Helpful guy. I thanked him and went in the general direction of where he had pointed. This “hallway of champions” turned out to be basically opposite the Forum’s main entrance, in a remote corner where I would normally expect to see bathrooms.

Let’s call that one a partial eclipse.

These things speak to why I personally believe that the pros of the 2008 IIHF celebration will always outweigh whatever cons I see. Mr. Fasel’s plaques were intended to preserve memories of things that would otherwise be forgotten for various reasons. There may be some general need for ‘hockey people’ to start checking out their own backyards and to think about whatever historical voids might need to be filled. I’ve learned from direct experience that Mr. Fasel’s thoughtfulness is certainly not to be taken for granted.

Imagine my surprise (as a hockey person) when I finally learned about that large stone that was about two blocks from where I had attended an elementary school in Oak Victoria, B.C. Only then, when I was in my forties, did I learn that I had grown up next to the former site of one of early Ice Hockey’s most historic buildings, the Patrick Arena. None of my classmates had any idea when I told them either. We had all walked right past the site countless times. That stone didn’t fall from the heavens, as I later learned. It was put there by former NHLers Russ and Geoff Courtnall and others. Since it was installed, the number of passersby who learned something remarkable about local history should be in the thousands.

In another act of stewardship, Pat Stapleton of Team Canada 1972, the original “Team Canada,” spent much of his remaining years building an educational program called 28,800: The Power of Teamwork. Pat’s program was based on the legendary Summit Series, contested between Canada and the Soviet Union over the month of September. Future generations of ‘hockey people’ may be pleased to know that such an initiative was undertaken by an actual 1972 Team Canada member, one who witnessed the series in real time rather than retrospect, from the first-person point of view.

There certainly was a huge “void” in Ottawa for quite some time. James Creighton’s grave remained unmarked there for more than a half century. How bizarre, given his stature and long-known connections to Canada’s capital city! Then again, how are people who don’t know hockey history even supposed to think about such things? And why should they care?

A group of members of the SIHR (Society of International Hockey Research) understood. They had a marker installed at their own expense. Others tried getting Creighton nominated to the Hockey Hall of Fame for at least ten consecutive years. The SIHR should be recognized for “standing on guard” for what some lovingly regard as “Canada’s Game.”

René Fasel did the same kind of thing at the Forum. He wanted to put the memories of a place and a person whom ‘hockey people’ really should be able to learn about them.

And now those plaques are gone, reminders of how easy it is to eclipse ‘big’ history.

End of digression.

* THE 2008: IIHF CENTENNIAL CELEBRATIONNext, we shall present some of the ways in which we differ with the IIHF’s way of describing Creighton and the VSR. Before going there, however, we wish to note up front that our opinions seem to differ from those of Jim Prime and Paul Henderson, another 1972 Team Canada member. Both seem to express agreement with Fasel in their 2011 book, How Hockey Explains Canada. The authors go even further, in fact: they say that the IIHF’s interpretations had the firm backing of various Canadian hockey notables. Here are the relevant passages, which appear in the first chapter.

Then again, maybe this so-called show of support isn’t quite what it appears.

After all, there is a big difference between supporting the general idea of enshrining Creighton and the VSR and agreeing with the IIHF’s specific conclusions about how best to describe them. Then there’s the inconvenient fact that none of these descriptions can be literally true, as all informed historians know. The question becomes: Is figurative usage acceptable?

We respectfully say no, not when it comes to Creighton and the VSR. There’s too much gravitas about them and too much potential to mislead the public, even when you don’t intend to.

Besides, Creighton’s and the VSR’s legacies are far too varied to be reducible to one-word descriptions. Creighton was a legislator of eternally enduring consequence. He was a promoter of lasting reputation. He was an entrepreneur of similar importance. He was the literal father of Montreal ice hockey. The reasons why we say these things are very well known. What is yet to be considered may be Creighton’s contribution. What he represented as an evolutionary figure should, in our opinion, provide the main reason for ice Hockey’s 19th-century ascent. Later on, we will explain why we believe that this must be his greatest contribution of all. Our point is that the figurative usage of “father” diverts attention away from the things that we know James Creighton literally accomplished.

Earlier, we said that many of today’s dominant theories ignore, overlook, downplay, or stereotype the contributions of our first two Stars. This is one such example, despite the IIHF’s noble intentions. They seem to have borrowed from a made-in-Canada way of thinking that has been decades in the making, and this is one of its more concerning results. Nowadays, Ice Hockey’s global governing body continues to write “Halifax” out of early history completely, as seen on their timeline-epochs page.

* 19th CENTURY ICE HOCKEY’S ‘RULE OF 1872’

As we said, the current imbalance between our depictions of Montreal and Halifax are real. It indirectly relates to how we go about deciding who introduced what in 19th-century Ice Hockey, In those discussions, ‘hockey people’ always borrow from a wider convention: victory generally goes to the earliest evidence in whatever thing is being considered. Quia sic dicimus claims are not enough, nor is poetic license. One must show evidence.

As for as Ice Hockey history is concerned, these subtopical discussions have been significantly affected by long-standing Montreal-centric biases that tend to rely on the diminishment or complete obfuscation of Halifax. How do these settled claims actually stand up when Halifax is included rather than ignored? With these considerations in mind, we introduce our Rule of 1872 :

In order for a community, game, or innovation, et cetera, to rightfully earn a place in the true story of early Ice Hockey’s evolution, one must show how such an item (a) emerged from or merged with Halifax ice hockey prior to James Creighton’s departure in ca. 1872, or (b) how it emerged from or merged with Montreal ice hockey after Creighton moved there. The earliest such reference is the best measure of an item’s true introduction into Ice Hockey’s evolutionary stream.

Just to be clear, anything introduced after 1872 or 1873 must merge with Montreal ice hockey for this reason: Montreal became the main definer of 19th-century Ice Hockey immediately after the Halifax transfer. We know this because of what Montreal ice hockey went on to become. The suggestion that Ice Hockey’s first goalie nets came from Nova Scotia, for example, or Ontario relies solely on the fact that “Montreal ice hockey” adopted nets, which, therefore, became a fixture in official Canadian “Ice Hockey.”

* SUBTOPIC: THE “FIRST WOODEN PUCK”

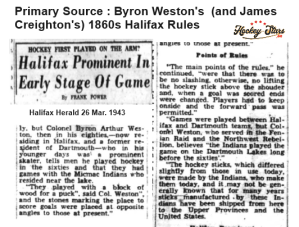

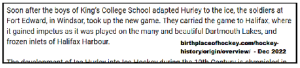

It is often said that Ice Hockey’s first wooden puck was introduced at the VSR on March 3, 1875. Following the Rule of 1872, our next move is to consider pre-1872 Halifax. Is there any earlier evidence of the wooden puck there? Indeed, there is. Hockey historians have known for at least eighty years now that blocks of wood were sometimes used in Halifax ice hockey, as early or late as the 1860s. Moreover, they know this from another must-know person in the story of early Ice Hockey, a Nova Scotia Supreme Court judge, former Dartmouth Amateur Athletic Association president, and former Dartmouth mayor, Bryon Weston.

Therefore, Montreal cannot be the place where the wooden puck was first introduced in Ice Hockey’s lineal story. It is just another myth that relies on a false 1875 genesis in order to sustain itself.

We must go further, however, if our goal is to determine the origins of the wooden puck rather than the city in which it first appeared. In turning to “Halifax” we must also consider the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw as well as the Halifax-Dartmouth settlers. In our previous essay, we found compelling evidence to suggest that the Mi’kmaq First Nation may have been using wooden pucks before the Halifax-Dartmouth settlers’ arrival in 1749.

Left unchecked, of course, myths have a way of building on themselves. As far as this subtopic is concerned, it has often been said that the rubber puck soon followed the wooden puck’s 1875 debut at the VSR. Some say it was introduced in Montreal. Others say Kingston. Sometime in the 1880s.

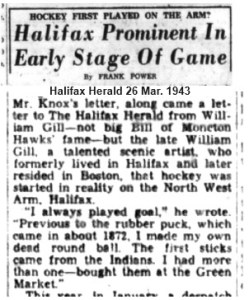

None of this matters, frankly. In 1943, William Gill, a contemporary of Creighton and a painter of some reputation, was quoted in the Halifax Herald as saying that the rubber puck had been introduced in Halifax “about 1872.”

Montreal can lay claim to the rubber puck’s first legislated appearance, or that of the “modern” puck, through the 1886 AHAC charter. In that document, the modern puck’s dimensions were mentioned in written form: 3 by 1 inches. This is too precise of a British imperial proportion to be something we can attribute to the Mi’kmaw. However, the indigenous partners may have used wooden pucks that were about that size. If so, the settlers’ exact 3″ x 1″ puck would have been inspired by a Mi’kmagi prototype.

The Rule of 1872 has taken us a long way from that superficial, figurative fairytale about the wooden puck’s so-called introduction. More fundamentally, as a simple way of thinking, it reminds us that the 1872–73 birth of Montreal and the 1875 VSR match are both equally important to real Ice Hockey history. The VSR match reminds us of what happened later in Ice Hockey’s evolutionary stream. The birth of Montreal points to what happened earlier. This lesson bears repeating in the current era. In order to understand how 19th-century Ice Hockey really evolved, Montreal and Halifax must both be carefully considered.

Earlier, we suggested that Canadians first began asking where Ice Hockey was born in the mid-1900s. Of the three civic contenders that emerged, Kingston dropped out of the running. The documented birth of Montreal ice hockey leaves only one contender. By default, it would appear that Halifax must be the literal birthplace of “the stick game that became Ice Hockey.”

Not so fast. Just before the turn of the millennium, a new theory emerged in which Windsor, Nova Scotia, was said to be the literal birthplace of Ice Hockey.

Once again, there were two civic contenders.

The Windsor theory was introduced in the 1990s by the late Dr. Garth Vaughan. Since then, it has enjoyed the backing of local politicians, local artists, and even the Department of Transportation. These kinds of things, combined with the city’s ongoing promotional efforts, have made Windsor one of the mainstream media’s go-to sources when it comes to the mystery of Ice Hockey’s birth. And why shouldn’t the media be interested? Dr. Vaughn claimed that the matter has been “proved” in the title of an essay that continues to appear at birthplaceofhockey.com, the Windsor theorists’ online home:

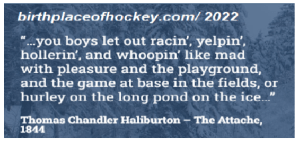

To our understanding, the basis of the Windsor claim is very straightforward. It is based on a passage in a book that was published in 1844, The Attache, by Thomas Haliburton. The well-known Haliburton was born in Windsor on December 17, 1796. This is said to be the central piece of evidence that Vaughn and birthplaceofhockey.com continue to cite as “proof” that Ice Hockey’s was born in Windsor. The website is overseen by a twelve-member Windsor Heritage Society. Here is the ‘key’ passage, where Haliburton reminisces on his school days at Windsor’s King’s College which he attended around 1805 to 1810.

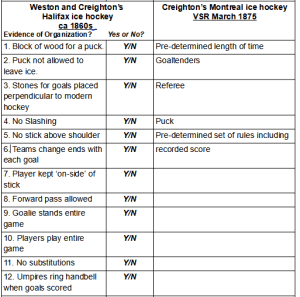

To our knowledge, there are no journal entries or reports that attest to such a specific Fort Edwards-to-Halifax transfer. If such information is available, it would be helpful if it were posted near Vaughn’s essay.

So, why Fort Edwards, then? Suppose there were twenty-five military settlements in colonial Canada when King’s College opened, aside from the one in Halifax. Why should we rule out the other twenty-four settlements in Fort Edwards’ favour? This is exactly what Henry Joseph’s testimony allows us to do in the case of the real-life Halifax-to-Montreal transfer.

Since Dr. Vaughn is no longer able to explain his thinking, we must hazard a guess. If Ice Hockey was literally born on King’s College’s Long Pond, Fort Edwards becomes the most logical choice for being the closest military settlement to King’s College.

It is important to know that the Windsor theory was developed before we became aware that people beyond Canada also played ‘stick games on ice’ during the pre-1872 era. This was a major revelation, but only to the extent that it falsified the notion that ‘stick games on ice’ first appeared in colonial Canada. Ironically, all of these new findings are beside the point in the lineal evolutionary sense. In this context, it doesn’t matter that Windsor ice hockey was “embryonic” at the time of its birth. All that matters is that it was transferred to Halifax at some point, prior to the Halifax-Montreal transfer.

Expressed in the terms we use here, Windsor supporters are saying ‘the stick game that became Ice Hockey’ was literally born in Windsor, through an exclusively European prehistory since Windsor’s literal birth only involved Irish hurling. (The other games entered their evolutionary picture later.) There it evolved for some time, as games usually do, before being transferred to Halifax, where it became a Windsor-Halifax game. After evolving further in Halifax, this singular stick game was transferred to Montreal. There it evolved further, now as a Windsor-Halifax-Montreal game, until it claimed the title of Ice Hockey by public acclimation in Canada prior to the end of the 19th century.

All of this adds to the Haliburton passage’s central importance, in the Windsor way of thinking, unless there is hard evidence of a Fort Edwards-to-Halifax transfer. Otherwise, it remains a claim, and one that seems to rely entirely on Windsor’s birth interpretation.

Those newly discovered “hockey” games tell us in no uncertain terms that Canada’s colonists lived during a time when people played stick games on ice on both sides of the Atlantic. In Windsor’s way of thinking, Halifax must be an exception to this rule. The colonists there must have never played stick ball on ice once, not until the arrival of the enlightened Fort Edwards soldiers following the opening of King’s College in 1788–89.

Is fence-sitting even reasonable here? We ask, because one must consider a roughly 5-by-4-mile area. In such a tight setting, is it reasonable to suggest that Halifax and Dartmouth colonists may have failed to notice the Mi’kmaw playing their ice game for four decades? We think not, and that others who say this have not thought seriously about Halifax-Dartmouth-Kjipuktuk.

We’ll close by emphasizing that this is only our understanding of the Windsor birthplace claim. We may be missing something big here. Perhaps by ‘proof’ the Windsor supporters mean something figurative. That would hardly be unprecedented in this space.

* The CBC’s HOCKEY – A PEOPLE’S HISTORY

* The CBC’s HOCKEY – A PEOPLE’S HISTORY

In 2006, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) did a very nice job of summarizing this depiction near the start of their highly entertaining TV series Hockey: A People’s History. Early on, one sees some colonists playing a stick game on ice with various kinds of sticks. The setting appears to be somewhere in Nova Scotia, perhaps Halifax-Dartmouth. As we watch their “scrum-like” game unfold—and man, does it ever look boring!—the narrator declares that ice hockey was a “wild, chaotic affair” with few rules in the mid-1800s. Why should anyone doubt him, given the involvement of the cerebral CBC?

By “CBC,” we refer to the editorial team that made the final decisions on this production. And the mid-1800s turns out to be an extremely important era in 19th century Ice Hockey. So, how much can “the CBC” actually know about Ice Hockey’s pre-Montreal era?

Not much at all, actually. In On the Origins of Hockey (2014), Carl Giden, Patrick Houda, and Jean-Patrice Martel cite a total of 23 Canadian colonial references to what is or may be ice hockey prior to the Halifax-to-Montreal transfer of 1872–73. If this is about right, the CBC is relying on 23 mostly very vague descriptions in order to generalize about an era that could have lasted up to 123 years, from 1749 to 1872, or prior to the birth of Montreal ice hockey. That’s one vague passage every five years or so.

In the fourth minute of Part One, the viewers’ attention is directed to a group of young settlers. The narrator tells us that they are entering a forest in order to cut down trees and make hockey sticks from their roots. This is a sad example of how our first Star gets so routinely ignored: The Mi’kmaw are left out of this depiction entirely, despite the fact that informed historians have known, since at least the 1870s, that the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw made hockey sticks out of tree roots.

Later on, the CBC’ narrator does mention the Mi’kmaw, but only as craftsmen of early Ice Hockey sticks. Not that I’m any better. If you had asked me around the same time, I would have almost certainly said the same thing and thought no further about the separate matter of invention.

It has long been assumed that Canada’s settlers invented the prototypical Ice Hockey stick and then hired the indigenous Mi’kmaw to make them. What never gets mentioned, because this theory seems to never get questioned, is the fact that there is no evidence of the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw being hired to make their hurleys, caymans, and grass hockey sticks for other Halifax-Dartmouth settlers. Why only hockey sticks? Did the Halifax-Dartmouth settlers get other First Nation groups to make their other Old Country sticks? What I’d like to know, is: who made their coffee tables?

Or, maybe colonists later hired the Mi’kmaw because earlier colonists had recognized the Mi’kmaq stick’s superior utility on ice! In what we regard as a most important aside, the Mi’kmagi storyteller, Jeff Ward, says that the original Mi’kmaq sticks were like today’s “hockey sticks.” We argued that Ward can only be alluding to the hockey stick’s end, which is defined by its “flat thin blade.” We should expect that the “flat thin blade” tended to inspire imitation everywhere it went. They would have been able to trade for them prior to the introduction of commercial stick-making. If those sticks were available in Kjipuktuk, when the Halifax and Dartmouth colonists arrived there in 1749–50, there would have been no need for those colonists to evolve Britain’s grass-adapted sticks into hockey sticks. Most frontier Canadians did not live so close to Mi’kmaw settlements. Those colonists had to make “flat tnin blades” by imitation at first until Mi’kmaq sticks became available for purcahs. Life was tough.

HALIFAX’S LEGISLATIVE DISTNCTION

* WESTON AND CREIGHTON’s 1860s HALIFAX ICE HOCKEY

It seems doubtful that the CBC would have described mid-19th-century “hockey” as wild and chaotic if they had carefully considered a newspaper article that hockey historians had known for more than sixty years prior to the debut of Hockey: A People’s History. Here we refer to the 1943 testimony of Byron Weston. Anyone who looks will likely come away thinking that Halifax hockey was wild and chaotic, especially when that game is described by a former Dartmouth mayor and former president of the Dartmouth Amateur Athletic Association, Bryon Weston. One would be hard-pressed to find a more reliable source than our Nova Scotia Supreme Court judge. The only thing that concerns us about Weston is that he never had a drink.

None of Weston’s accolades describe the main reason why he simply must be considered, in any true telling of Ice Hockey’s rules. The most important thing is that we know that Weston grew up with James Creighton from the age of ten. James Creighton was born in Halifax on June 12, 1850. Weston was four months younger and moved to Halifax around 1860. Both were known athletes, and they may have played together for up to twelve years before Creighton moved to Montreal. Both would go on to law school. In the 1860s, Halifax-Dartmouth had about 35,000 people, and there was much illiteracy. Only ten percent of the population belonged to Weston’s and Creighton’s upper classes.

These things seem to make it unreasonable, beyond a reasonable doubt, to not consider Weston’s rules in attempting to describe the origins of Montreal’s rules. To see why, let’s revisit the “Rule of 1872.”

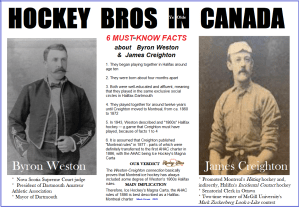

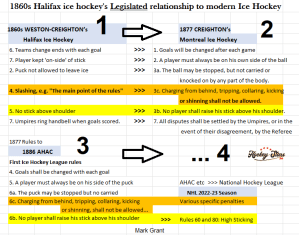

On the left side of the table below, one sees Byron Weston’s description of 1860s Halifax ice hockey. On the right are some of the reasons why the later March 3, 1875, match is said to be Ice Hockey’s first organized game. The only way the VSR match can hope to be Ice Hockey’s first organized game would be if all of Weston’s earlier Halifax’s rules do not reflect “organization,” in accordance with the rules of common English rather than the whims of literary invention. Otherwise, Weston’s Halifax ice hockey must have been “organized” to some degree, and we must assume that some of Weston’s rules were transferred to Montreal through the ironclad Weston-Creighton connection.

Mentally circle ‘N’ each time you think a Halifax rule does not reflect some form of organization. Answer ‘N’ to all of the items, and the March 3, 1875 VSR match may be the first instance of organized hockey. Circle ‘Y’ once, and that distinction goes to Halifax.

* HALIFAX’S ‘LEGISLATIVE‘ PLACE IN MODERN ICE HOCKEY

Here’s the relevant portion of the article where Byron Weston’s rules first appeared in 1943. A heads up: it has been our experience that the lists one sees online of “Weston’s Halifax rules” usually differ from this original copy. For example, several lists say that Halifax ice hockey was played with two 30-minute halves and a 10-minute break. Others may have found that information elsewhere. We couldn’t find it here.

It won’t be easy to find a piece of evidence that is more important to early Ice Hockey than the newspaper article where Byron Weston’s Halifax rules appear. It is essential to know about because it details the 1860s game that Weston must have played with James Creighton from the age of ten.

The main “evolutionary” implication of this vital Weston-Creighton connection goes as follows, in our opinion: It becomes most reasonable to expect that some elements of Weston’s 1860s Halifax game discreetly appear in the famous 1877 Montreal rules, since the latter rules are said to have been written by Creighton. The more one thinks about the Weston-Creighton connection, the more unreasonable it becomes to completely separate Weston’s rules from Creighton’s, as we have been doing now for more than eighty years.

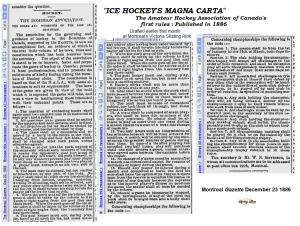

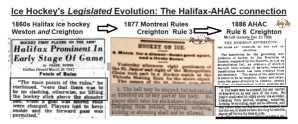

This kind of Halifax-Montreal or Weston-Creighton transference appears in the first Montreal rule, where Creighton repeats Weston’s rule about Halifax players changing ends after each goal is scored. This rule was also transferred to the first AHAC rules, which were drafted at the Victoria Skating Rink in 1886—some twenty years after Weston described 1860s Halifax hockey. The three-way transfer relationship between the 1860s Halifax rules, the 1877 Montreal rules, and the 1886 AHAC charter is vitally important. We suggest that the most important 1877–1886 connection is between the AHAC’s Rule 6 and 1877’s Rule 3. They provide verbatim proof of transfer. They should compel us to ask if Montreal’s 1877 Rule 3 can be similarly linked to Weston and Creighton’s 1860s Halifax game. If so, we have a very significant Halifax-AHAC connection. Here are the relevant textual references:

Starting from the left: our main argument is that Weston’s “main point” about the Halifax rules is best understood as the principle of gentlemanly play. He expressed this general idea in two specific ways: through the rule about keeping one’s stick down below the shoulder—no “high sticking”—and through the prohibition of “slashing.” Both of these Halifax rules were also transferred to the 1877 Montreal Rules.

James Creighton restated Weston’s “main point” about gentlemanly play in greater detail in Rule 3 of the 1877 Montreal rules. He mentioned five new infractions: “charging from behind, tripping, collaring, kicking, or shinning shall not be allowed.” This would not have been necessary back in Halifax. It became necessary in Montreal, “soon” after the 1872-73 transfer, because the Montrealers began permitting some forms of predatory hitting. This decision made playing Ice Hockey more complicated.

From then on, two major forces helped shape the evolution of early Ice Hockey rules. Both concerned themselves with the matter of what constitutes gentlemanly play. Creighton described some of the new acts that were tolerated through the letter of the law. Various unspeakable infractions were not legislated at first, however. But they were surely not tolerated either in Halifax or Montreal. These unlettered infractions were covered by the other side of Ice Hockey’s self-regulating coin.

That is, elbowing, cross-checking, and so on were all surely regarded as unsportsmanlike infractions before their specifics got written in code. In those situations, the Montrealers would have invoked Weston’s principle of gentlemanly play, and the player involved would have been reprimanded. Prior to their actual legislation, these ungentlemanly acts were covered under the Montrealers’ “unwritten” code of conduct. That aspect of organized Ice Hockey was transferred to Montreal, via Weston’s 1860s Halifax rules and is implicitly present in James Creighton’s 1877 Montreal rules.

Inevitabley, any discussion of how Weston’s rules may lead to Creighton’s leads to the first AHAC rules of 1886, where one sees verbatim transfers of some elements of the 1877 Montreal rules. This must-know document’s greatest distinction is analogus to England’s 1215 Magna Carta relative to the legal domain. It is ‘the’ document on which all versions of modern Ice Hockey are based. Its Halifax elements prove that Montreal inherited something other than a wild and chaotic game.

The original AHAC rules were likely tweaked from year to year, before being transferred to the Canadian Amateur Hockey League (CAHL), which was a reinvention of the AHAC. This set a precedent that would repeat itself many times, a process of transfer and reinvention that was most fundamentally based on the AHAC’s Halifax-Montreal rules.

Many Canadian leagues entered Ice Hockey’s dominant stream early, by way of the AHAC or when the CAHL defined dominant hockey, during the AHAC-CAHL era. In 1908 the IIHF adopted an AHAC-CAHL-CAHA version of the original 1886 AHAC charter, when the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association was dominant. The IIHF adopted what was the latest version of an ever-evolving Halifax-Montreal rules template. Then the CAHA morphed into the CHA, the Canadian Hockey Association, this lineal path’s first professional league. To state things most succinctly, this process of league reinvention led to the NHL, via a process of transfers that looks like this in shorthand:

AHAC–CAHL-CAHA-CHA..etc… NHL .

With this in mind, consider the yellow line in the diagram below. In box 1 we see Weston’s rule on high sticking. In box 2 we see that Weston’s rule was transferred to the Montreal rules of 1877. Box 3 shows us that the same high-stick rule was transferred to the AHAC in 1886- to our vital connection, the point where all leagues can be tranced back to. Box 4 takes us down one such path, to the National Hockey League: AHAC-CAHL-CAHA-CHA..etc… NHL.

Byron Weston’s rule about high sticking lives on in NHL hockey, where it is presently immortalized through rules 60 and 80, via a process of transfers that lead back in time, beyond the AHAC’s founding at the Victoria Skating Rink, to Halifax-Dartmouth-Kjipuktuk. And, therefore, also European, International, Olympic and now global Ice Hockey.

Slashing follows a similar route via the orange path, with a twist. At the Box 1-Box 2 point of transfer, we must assume that slashing remained prohibited in 1877 Montreal hockey, even though it wasn’t explicitly prohibited. This locks Halifax’s connection to modern Ice Hockey’s various slashing penalties, beyond a reasonable doubt. The orange way of thinking reflects that unlettered side of that proverbial coin we mentioned. It requires that we resort to commonsense. Fence-sitting doesn’t work in this case either, if anyone thinks that it might. It is most unreasonable to think that Creighton would have or even may have told his new friends that slashing was okay.

To what we were saying earlier, one could legitimately say that later penalties like elbowing, spearing, and so on, are further elaborations of Byron Weston’s main point about gentlemanly play. Our main point is that some Halifax rules were definitely transferred to the AHAC via the Montreal rules. This is what secures Halifax’s immortality when it comes to modern Ice Hockey’s rules. This is its great “legislative” distinction.

* * *

I’ll close this section by paying the Victoria Skating Rink one last visit, changing one last thing.

Another Canadiens’ game is about to start at the nearby arena. Various ‘hockey’ people stream by a brick parkade. But for one thing, all would think that it was nothing other than a temporary shelter for transient cars and the home of a coffee shop. Gord stops, momentarily, having noticed a plaque.

“Hey Marge, get a load of this…

“It says, ‘All versions of Ice Hockey’s rules, worldwide, are and will always be derived from a document that was written on this site, on the evening of December 8, 1886.’

How about that!?

They read further, since the plaque lists other details of similar epic consequence that literally happened on the other side of the wall where they stand. “How about that!” Time for a selfie, and before you can say, “This present situation is unacceptable,” Junior is opening the VSR pic in some faraway suburb. Just then the doorbell rings. It’s the pizza guy. A famished Junior forgets all about the pic. Then he accidentally trashes it two days later.

This is just one scenario, however. Of course. More than one selfie will be taken on that imaginary day, among others. Images of the plaque will find their way to social influencers. They will be read, the Victoria Skating Rink’s amazing legacy will be properly reintroduced. Visitors will start looking for the plaque when they come to town, hockey people in particular. For being so close to Ste. Catherine’s, it will be very easy to reach. Next thing you know, businesses in that neighbourhood start calling March 3rd Victoria Skating Rink Day, and people are circling the block around the Autoparc Stanley to get a taste history inside the Melk Cafe.

How much do plaques cost, anyway?

(I wouldn’t know, personally. I’ve never been awarded one.)

Seriously, if ‘hockey people’ are okay with letting these memories fade, that’s really okay with me. Whether anyone else sees another “void” is an individual thing. I totally get that, and accept that. Nonetheless, it does surprise me that I saw nothing to commemorate the Victoria Skating Rink on or near the Autoparc Stanley. I mean, come on—that building, in that equally storied neighbourhood! To bring this all home, my recent trip to Montreal was great. It was a positive one for many reasons, although I may have seen more “eclipses” than I bargained for.

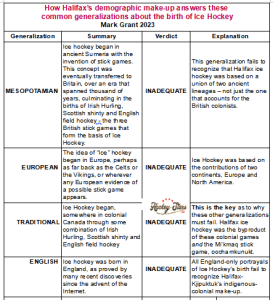

* ON NAKED GREEKS, GORDIAN KNOTS AND THE ‘TRADITIONAL’ WAY OF FRAMING “HALIFAX” We return to the discussion of various things that Halifax ice hockey was not, and the CBC’s Hockey: A People’s History. Early on, in describing how Ice Hockey was born, the narrator said that “winter’s greatest sport,” a.k.a. modern Ice Hockey, was born in summer under the hot sands of Egypt, Persia, and Greece. As he speaks, the viewer’s attention is directed to the nearby image of a 2,500-year-old carving from the Parthenon in Greece.

It’s not difficult to see the intent here. We get it. People played stick games in the ancient world. The CBC likely mentioned “Egypt, Persia, and Greece” because of colonial Canada’s connection to Britain and France. If so, they are basically equating the long march of Mesopotamian-Western civilization with Ice Hockey’s evolution based on a single carving. We know that Montreal ice hockey inherited a Halifax game that was the byproduct of two parent continents. Canada’s main social influencer has failed to mention the North American lineage. In doing so, they have left the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw out of Ice Hockey’s creative process entirely.

Archeologists know that the earliest Mi’kmaq First Nations people began settling in present-day eastern Canada around ten thousand years before the Parthenon was erected. The CBC appears to have borrowed the “Traditional” interpretation of Ice Hockey’s birth in making this generalization—the theory that Ice Hockey emerged from some combination of Irish hurling, Scottish shinty, and English grass hockey. Had Ice Hockey evolved from those sticks only, it would have been perfectly appropriate to mention the ancient Greeks, since Britain emerged from the same evolutionary stream. The Traditional theory fits many frontier Canadian communities, as we were saying. In reality, it does not, because the rule of history says one must recognize Halifax-Dartmouth-Kjipuktuk.

In our exploration of early “hockey” history, we’ve seen a number of generalizations that are based on the same core fallacy. None are more famous than the new claim that ice hockey was invented in England, some time after 1066 AD. This is very understandable, since this is where so much of the new evidence points. The English invention theory also fails epically, for the same blinkered reason. Imagine saying that you were born in England even though you were born in Halifax, just because your dad was born in England. We can’t have that, can we?

A whole category of popular claims rely on this form of Halifax’s superficial consideration. All recall that Gordian Knot that we introduced at the start of this essay. All fail because they don’t recognize our first two Stars. They are inadequate at all levels. The solution is not to trash the Traditional theory. We only need to amend it, for the same reason that one must never ask for a table for three when entering a diner as a party of four.

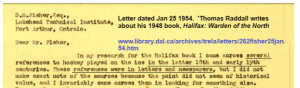

As for how Ice Hockey really began, in the first essay, I proposed that the first on-ice meeting between the indigenous and colonial partners must have taken place sometime before June 25, 1761. That was when the Mi’kmaw and the British military signed what turned out to be a lasting treaty.

Later, while writing this essay, I discovered a letter that was written in 1954 by the Order of Canada historian, Thomas Raddall. In the letter, Raddall tells a dentist that the “first” settlers saw the Mi’kmaw playing their stick game on ice. He added that he found “several” references to the Mi’kmaq stick game being played in the 1700s and 1800s while researching his famous 1948 book, Halifax: Warden of the North, hinting at the possibility that we may find such direct references to the Mi’kmaq game by following his footnotes.

The image below links to Raddall’s letter. Raddall’s claim about the British military members encountering the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw as they were playing makes great practical sense. It does when Halifax’s demography is given the slightest consideration. The British military would have kept a very close eye on the general area from the first day. They would have known where the Mi’kmaw gathered. If the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw were anything like today’s Canadians, we should expect that the British saw the Mi’kmaw playing their version of pond hockey in the first winter or very soon after. An initial encounter at Tuft’s Cove is very plausible, if not most likely.

We must keep in mind, however, that Raddall offers no direct proof of this claim. We must therefore try to find the best theoretical explanation.

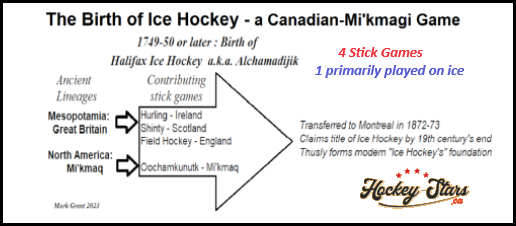

Recalling the Traditional theory: we amend it to say that ‘the stick game that later became Ice Hockey’ was born through ‘some combination of four stick games, Irish hurling, Scottish shinty, English field hockey, and the Mi’kmagi ice game which we understand was called oochamkunukt. (The name is of secondary importance to the fact that the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw played some kind of stick game on ice, as most historians will likely agree. Here is the adjusted theory in diagram form.)

* THE “SAME GAME” GENERALIZATION REGARDING ALL PRE-MONTREAL ICE HOCKEY

In another common way of thinking these days, Halifax’s lineal distinction doesn’t matter even though it cannot be denied. It says that all of pre-1872 Halifax ice hockey was a big nothingburger not worth mentioning. James Creighton might just as well have introduced Montrealers to a random stick game from anywhere in Britain, or Kingston, Pictou, or Boston. The point being that “hockey” remained the same until those those Montrealers got involved.

The VSR mythologies rely heavily on this treatment. If Halifax can be downgraded enough, it doesn’t require mention. If it does require mention, it must be described as yet another pre-Montreal game devoid of rules.

How did we get to this point, where some write Halifax out of Ice Hockey history entirely? We suggest it was the result of three forces that began coalescing just before the turn of the millennium.

The main driver, surely, was the mid-1990s introduction of the Internet. The digitization and widespread circulation of old periodicals literally proved that the concept of playing a ‘stick game on ice’ was not necessarily a Canadian creation. These new revelations called for a major reassessment of Ice Hockey’s presumed origins.

Meanwhile, around this time the Windsor, Nova Scotia, birthplace theory emerged. Widely promoted by Windsorites and local politicians, the Windsor theory soon became somewhat of a media darling. As such, there was considerable attention when, in 2002, some members of the Society of Hockey Research (SIHR) published a review of the Windsor birthplace claim. In making their assessment of Windsor, the SIHR members offered a definition of Ice Hockey that was based on two dictionary definitions.

“The wording we have agreed upon, borrowed or adapted from, in particular, the Houghton Mifflin and Funk and Wagnalls definitions, contains six defining characteristics: ice rink, two contesting teams, players on skates, use of curved sticks, small propellant, objective of scoring on opposite goals. Thus, hockey is a game played on an ice rink in which two opposing teams of skaters, using curved sticks, try to drive a small disc, ball or block into or through the opposite goals. (www.sihrhockey.org/__a/public/horg_2002_report.cfm:)

This definition of Ice Hockey was likely of secondary importance to the SIHR members, whose main interest was the Windsor evaluation. Over the last quarter century, however, the SIHR’s definition of “hockey” may have garnered more media attention than the Windsor evaluation! Taken from two dictionaries, this definition has become a zeitgeist king, an easy-to-access way of describing all pre-Montreal versions of “hockey” on ice.

Working with the SIHR’s definition of “hockey,” there is lineal hockey and non-lineal hockey. Lineal hockey refers to the singular game that all versions of modern Ice Hockey can be traced to: the 19th-century Halifax-Montreal version of “hockey,” which officially became Ice Hockey in Canada by the end of the 1800s. Non-lineal hockey refers to all of SIHR’s other “hockey” games. They are background performers in a 19th-century story of conquest that co-starred Halifax and Montreal only. Therefore, the SIHR’s definition encourages people to equate pre-Montreal Halifax ice hockey with the versions of “hockey” that Halifax ice hockey resoundingly conquered.

In fairness and as noted, however, one might think that all pre-1872 ‘hockey’ games were the same, based on the preponderance of visual evidence that’s been discovered over the Internet’s first thirty years. * NON-LINEAL “HOCKEY”The two outer images on the three-part panel below are quite typical of what many would call “new evidence of pre-Montreal ice hockey.”

We place a modern shinty player in the middle panel. Note the similarities and differences. Here are two questions:

1- The 1855 London, England image on the left is described as a ‘hockey’ game. So, what game are the players on the right playing: are they playing ice ‘hockey‘ or ice ‘shinty‘?

2- What is your level of certainty?

Welcome to the often vague world of 19th century ‘hockey’ evidence. Here’s an 1840s passage from Halifax, where one Mrs. Gould mentions hockey and a game called rickets. She is speaking about two different games here. Where the rules of English matter, the point is non-negotiable.

However, five sentences earlier, Mrs. Gould says that rickets “is” hockey!

Starting with the first quote, if Mrs. Gould is correct in saying that hockey and rickets are different games, then she must have made some kind of mistake about saying hockey and rickets are the same game five sentences earlier. Or, one can reverse the logic where the latter statement is true. Or, and this is our position: one can conclude that Mrs. Gould’s description is not conclusive.

One thing that we do know conclusively is this: There was a stick game called rickets that was played in Nova Scotia during James Creighton’s childhood. And that stick game most closely resembled Irish hurling on ice. When James Creighton was nine years old, an American reporter visited Nova Scotia and wrote the following words in a Boston Evening Gazette article that was published on November 5, 1859.

“From the moment the ball touches the ice, at the commencement of the game, it must not be taken in the hand until the conclusion, but must be carried or struck about ice with the hurlies. A good player – and to be a good player he must be a good skater – will take the ball at the point of his hurley and carry it around the pond and through the crowd which surrounds him trying to take it from him, until he works it near his opponent’s ricket, and “then comes the tug of war,” both sides striving for the mastery.”

In Byron Weston’s and James Creighton’s Halifax hockey, carrying the puck was expressly prohibited. Their version of Halifax ice hockey was a different game than the Boston reporter’s rickets.

Which game is this: ice hockey or ice shinty?

Of course, many casual observers would incorrectly think they were watching ‘hockey’ when, in fact, they were watching ice hurling or ice shinty. We say the distinction doesn’t matter. It very well may, if you were a settler of Irish or Scottish descent. It wouldn’t have, to a lot of settlers, some of whom wrote journal entries, just like Mrs. Gould.

There really is no need to try and make all pre-1872 stick games into one activity, hockey, as some have. The diverse societal make-up of Halifax-Dartmouth strongly favours the opposite approach. Various stick games were played on the ice. Over time, ice hockey definitely became the dominant stick game around Halifax in the winter—after 1859, apparently, when rickets (hurling) reigned supreme.

It is easy to see how the terms shinney and hurley became ways to refer to pond hockey, given their clear relationship to Scottish shinty and Irish hurling. The term rickets was surely borrowed from the game of cricket. From the Irish point of view, naming their ice game after such novel goals may have been a sensible way to distinguish ice hurling from proper hurling in casual conversation.

Mrs. Gould’s cautionary tale is a reminder that we must never grant casual viewers infallible powers of observation, just because the speaker lived during this era. A very early witness to Montreal ice hockey infers that such rushes to judgment were quite predictable, even in 1877.

I take these things to mean that the names associated with mid-19th century games may be less revealing than how the games played out, if that can be determined. For the record, the third panel image is supposedly of a hockey game. So is the third, an 1867 image that is linked to Boston.

We can indeed predict how these non-lineal stick games played out:

The London and Boston players’ raised sticks and short stick ends tell us that there must have been a lot of hitting and, therefore, chasing the ball or puck. 19th-century grass fields used for shinty and grass hockey were sometimes up to 200 yards in length. Hitting is the only way to best direct a ball in such environments, which require sticks with short club-like ends that have relative thickness. The sticks one sees should work very well in such settings. On ice, however, they suck (unless everyone doesn’t know better). Non-lineal sticks like those preclude combination play and stickhandling, and “hockey’s” potential to evolve.

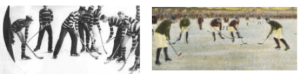

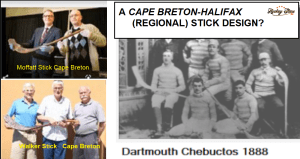

* SWEEPING vs. HITTINGThe photos below show examples of lineal sticks. They have what we called ‘flat thin blades’ earlier. This is the prototypical stick-end that lives on in modern form.

Both photos also show lineal Ice Hockey. They must because both photos are from Montreal. Dated to 1881, the left-side image is said to be the world’s oldest Ice Hockey photo. The other shows an 1893 Victoria Skating Rink match in progress. Twenty years have passed since the Halifax-to-Montreal transfer. AHAC hockey has just become Canada’s official version of Ice Hockey. Less than a year earlier, the Stanley Cup was introduced and linked to AHAC hockey.

Ice Hockey’s central mandate involves trapping, protecting, and directing the puck better than one’s opponents. Such an activity requires sweeping, not hitting, for being a version of “hockey” that is played on ice. Such an activity requires sticks with flat thin blades. This explains why London and Boston players sticks would prove to be non-lineal. In doing so, it also explains why non-lineal sticks should never be confused with those made by the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw.

The fact that the Mi’kmaw played with the colonists around Halifax is very significant, and affirmed in the nearby split image. On the left side, we have Byron Weston describing 1860s Halifax ice hockey. In the right-side article, the Mi’kmaw elder, Joe Cope, confirmed a few days later that he played with Weston.

Cope’s mention of playing with Weston “and other old players” is also very important, as it infers a setting where Halifax hockey was played on an ongoing basis. Cope implicates James Creighton, by extension. The two may have played together, although Creighton was around twenty-two when he moved to Montreal, when the extroverted Cope was around thirteen. We should note that Cope spoke of ten-player teams, since only Weston’s details are usually mentioned. So much for the idea that equally-numbered teams were introduced at the VSR in 1875, via nine-player sides. What a major revelation that would be, if nobody ever thought up such a practical idea in Halifax.

If the Mi’kmaq game was based on its stick’s end, as we proposed, one would have a game that encouraged players to lean downwards, for the primary purpose of sweeping rather than hitting a puck-like object. Seen in the wider context, we have this indigenous game, versus three others that encourage hitting balls and lots of raised sticks. As such, Weston’s prohibition against raised sticks and carrying the puck may also read like old Haligonian: “Play your (ice) shinty and (ice) grass hockey and (ice) hurling elsewhere!”

It’s interesting to think that today’s various “high sticking” penalties might have emerged from such a mundane local consideration. Weston’s singular mention of slashing seems to point to the same very reasonable concern. With all of those other players around, it became necessary to discuss stick management in general.

There was no need to announce that it was not okay to punch a guy in the face. That was understood, as were many other things. We can also be assured that ruffians didn’t flaunt the rules in the “hockey” settings where families like the Westons and Creightons of Halifax played. Few would have dared challenge the local authorities during that period in history. A slashing penalty could easily result in jail time, or worse.

Such insubordination was hardly necessary, however. We know that thousands of people skated around, on, and in between Dartmouth and Halifax in the decades prior to James Creighton’s move to Montreal. Those who wanted to play like the London and Boston players could do so easily elsewhere. Many would have done so gladly because their visions of a “proper” winter stick game were based on games that were primarily played on grass.

Therefore, Halifax players like Cope, Creighton, and Weston would have been able to play their gentlemanly game in relative peace. The Mi’kmaq sticks would have enabled them to evolve their game, during an era when other “hockey” players cluelessly chased pucks in what, for them, were the Dark Ages.Joe Cope’s involvement in Halifax ice hockey also reveals that others could play with Halifax-Dartmouth’s governing class. This is certainly worth mentioning, during these times of “Reconciliation” in Canada. The partnership between the Mi’kmaw and the Halifax-Dartmouth settlers stands as a major beacon of light, in an otherwise dark and difficult era. I said that the partners’ legacy must be one of early Canada’s greatest Untold stories for a reason. Look around you during winter, and you will always see signs of their enduring success.

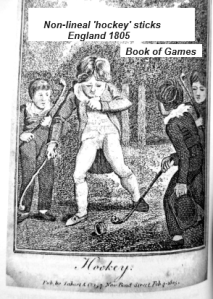

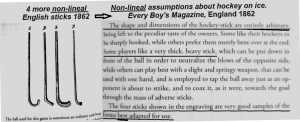

* INTRODUCING THE “HALIFAX” TAKE-OVER On that note, let’s circle back to the SIHR’s 2002 definition of hockey. Since it makes no distinction between playing sticks, it must follow that the 1805 sticks seen nearby are “the same” as Halifax’s entire pre-Montreal inventory. Likewise with the four 1862 English sticks shown below. The 19th-century English author who refers to them tells his English audience that one’s preferred stick-end is “entirely arbitrary.” Such a remark would not go over well in Tuft’s Cove.

On that note, let’s circle back to the SIHR’s 2002 definition of hockey. Since it makes no distinction between playing sticks, it must follow that the 1805 sticks seen nearby are “the same” as Halifax’s entire pre-Montreal inventory. Likewise with the four 1862 English sticks shown below. The 19th-century English author who refers to them tells his English audience that one’s preferred stick-end is “entirely arbitrary.” Such a remark would not go over well in Tuft’s Cove.

In fairness, we should mention that these sticks were placed in a discussion about grass hockey. We show them only because they have been offered up as early ice hockey sticks. That’s what happens when you introduce a definition of “hockey” that must include all “curved” sticks. The moment these sticks are taken to ice, the SIHR definition will put them in the same place that they have put the Mi’kmaq First Nation’s entire pre-Montreal inventory.

We are saying that merely curved and crooked stick are not the same as this stick and others like it, sticks that have flat thin blades. They can’t be, if your objective is to trap, protect and direct a puck better than you opponent on ice:

We are saying that merely curved and crooked stick are not the same as this stick and others like it, sticks that have flat thin blades. They can’t be, if your objective is to trap, protect and direct a puck better than you opponent on ice:

1 of 3 – HALIFAX TAKEOVER: ICE HOCKEY’S REVOLUTIONARY STICK

1 of 3 – HALIFAX TAKEOVER: ICE HOCKEY’S REVOLUTIONARY STICK

The “flat thin blade” tamed the puck-like object. It enabled “hockey” to evolve. In our previous essay, we said it had six essential elements, all of which must remain present to make a prototypical Ice Hockey stick end. A proper flat thin blade must be relatively thin, relatively flat on both sides, and relatively flat to the ice. It mustn’t be too high (like a goalie stick), or too low, (worn-out street hockey stick), or too long (Pinocchio’s nose).

This is the design that we are told the Canadian settlers’ sticks slowly evolved towards. The stick’s elements will vary from one place to the next, but all six elements will tend to be preserved once their collective advantages are noted. The flat thin blade enables a user to pass or shoot forehand and backhand in any direction and to trap a puck on a dime. It radically improves a player’s ability to elude opposing players while enabling teammates to work together so that they “protect and direct” pucks at exponentially higher levels of efficiency. None of these things are possible with non-lineal sticks, as the “new” evidence so plainly reveals. We must take care to not paint early Canada with the same brush. Slow evolution did not occur everywhere “hockey” was played. It seems much more likely that the flat thin blade abruptly ended all such evolutions wherever it appeared, quickly, if not immediately. Ice Hockey is predicated on the flat thin blade.

So, who introduced it?

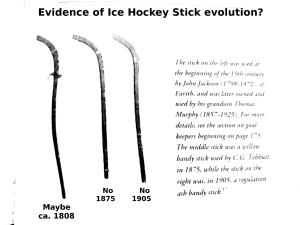

I’ll say in advance that we don’t know. What we do know, however, is that there are only two continents to consider. Which continent introduced the flat thin blade to ‘the’ stick game that became Ice Hockey? Since we know that the flat thin blade was in use in Montreal as early as 1878, we must ask where it was previously introduced in this, lineal Ice Hockey’s evolutionary stream.: In Halifax or Montreal? This time we will apply the Rule of 1872 in the opposite direction, asking how the flat thin blade may have been introduced to Halifax via Europe.

The earliest European flat thin bladed stick that we know of was owned by John Jackson, who was born near Cambridge, England in 1898. We shall call his device the Cambridge stick and date it to Jackson’s 10th birthday. Seen on the far left side of the image below, Europe’s and Britain’s oldest ‘flat thin’ blade dates to “around 1808.” This is well before the Halifax-to-Montreal transfer of 1872-73, meaning that such a purely European stick-end could have reached Montreal by way of Halifax in theory.

In the Cambridge stick’s case, we have no Henry Joseph-like proof of transfer. Nor do we know of any other English stick that closely resembles the flat thin blade, from the founding of Halifax in 1749 until the 1872-73 Montreal transfer. We must try to make our best generalization, regarding how a Jackson stick could have merged with pre-1872 Halifax ice hockey.

Cambridge, England, is said to have been involved in Bandy’s evolution prior to that game’s formalization at Oxford in the late 1800s. Cambridge and Oxford are also home to two of England’s finest schools, where English military officers like the ones that Raddall mentioned. As we noted in our first essay, Lord Stanley’s Eton played some version of “hockey” before 1872, the time of the Halifax-Montreal transfer.

The Cambridge stick’s flat thin blade would have made quite an impression in English settings where others used curved or crooked ends. We should expect that it inspired some degree of imitation, there, since we say that this is what happened across Canada. Given Cambridge’s proximity to elite schools that sent officers over to Canada routinely, it is very plausible that such an English prototype could have inspired imitation in Canada, although not so much in the first place that we must consider: Halifax-Dartmouth-Kjipuktuk.

Before moving on to North America, we note something ironic. When we apply the same logic – of transferring sticks from one continent to the other, it seems equally plausible that John Jackson’s Cambridge stick was inspired by a Mi’kmagi prototype.

Keep in mind that the British officers would have begun returning from Canada to Britain not long after 1749. This was nearly fifty years before Mr. Jackson was born in 1898. We must consider Lord Stanley’s officer network in this light. England, which reinvented itself from year to year during this half century, one sees a very legitimate possibility that the Mi’kmaq stick played a significant role in the evolution of Bandy. This way of thinking seems to have never been considered, likely owing to the colonial bias of the Traditional interpretation.

This is not a zero-sum subtopic. The flat thin blade could have emerged in Bandy and Ice Hockey independently of each other’s influence.

2 of 2 – NORTH AMERICA MI’KMAQ FIRST NATION

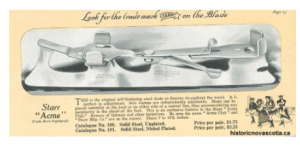

The Laval stick is the oldest North American “hockey” stick that we know of that has a “flat thin blade.” Scientifically dated to 1776 +/- 20 years, it precedes the birth of Cambridge’s John Jackson by a few years. More importantly, it brings us very close to the first British colonists’ arrival in what was then Kjipuktuk only in 1749.

The Laval stick’s owner, Brian Galama, linked it to Canada’s colonial military. This is exactly the kind of thing that we should find, according to the Order of Canada historian, Thomas Raddall. However, I was unable to reach Mr. Galama while writing my previous essay. For now, the only thing that seems certain about the Laval stick is its age. This proves the oldest known North American flat thin blade is older than the oldest known one from Europe, as of 2024.

The Laval stick’s owner, Brian Galama, linked it to Canada’s colonial military. This is exactly the kind of thing that we should find, according to the Order of Canada historian, Thomas Raddall. However, I was unable to reach Mr. Galama while writing my previous essay. For now, the only thing that seems certain about the Laval stick is its age. This proves the oldest known North American flat thin blade is older than the oldest known one from Europe, as of 2024.