As noted in our previous essay, this presentation is a one-person project, brought to you by a ‘yours truly’ who sometimes refers to himself in the plural. Our “Ice Hockey” includes all variations of the modern game. For more specific versions of “Ice Hockey,” we phrases like ‘Montreal ice hockey, NHL ice hockey, women’s, junior and Olympic ice hockey, and so on. This essay concerns our last two Stars and can be found in our book, The Four Stars of Early Ice Hockey.

In this presentation, the first era of 19th century Montreal hockey lasted for around two years. During this period, the Montrealers played among themselves. Two groups gathered with some regularity. One was associated with McGill University; the other with the Victoria Skating Rink. Both settings were within walking distance of each other.

We should probably expect that James Creighton ordered at least one or two more batches of sticks over the first two years. Henry Joseph says his group played almost every day. The founding fathers of Montreal had friends. Others around McGill and the VSR probably wanted in too. The cloning process mentioned earlier was extended further. One by one, other Montrealers became ice hockey players who used Dartmouth’s skate and the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw’s stick. They became radix stellaris hockeyists. Weston, Cope and the others would have been keenly aware of these Montreal orders through which a vitally important Halifax-Montreal pipeline was introduced by that son of Halifax, James Creighton.

By the end of the 1874-75 winter, Montreal’s core players must have gotten pretty good. After two years of being seen around McGill and the central downtown area, they likely gained some confidence in the entertainment value of their game. Creighton may have noted how the early enthusiasm around Montreal reflected the sudden rise of Halifax ice hockey after the 1863 introduction of the Acme skate. His entire teen years had been spent witnessing that growth.

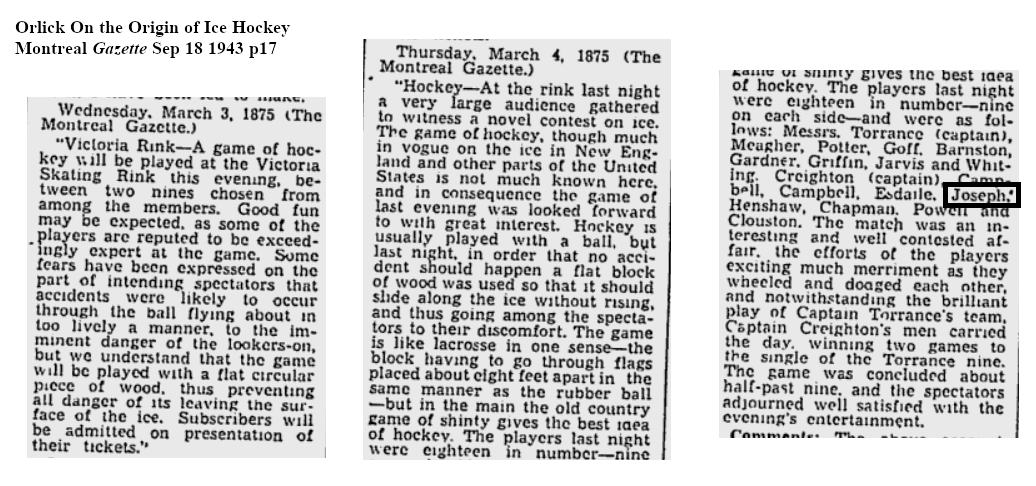

To be clear, the March 3, 1875 demonstration at the Victoria Skating Rink episode doesn’t mark the “birth” of hockey in any meaningful sense. Still, it was a major step in our 19th century stick game’s second phase of organization. Halifax set the table in the first phase or organization, defining the basic rules and ways of playing – with sticks down and without hitting the puck, as was the custom in Britain’s stick games. In the second phase, Montreal began introducing their own twists. The result was a new hybrid version of Halifax-Montreal hockey.

We concluded our last essay by noting how integral Halifax’s Dartmouth skate and Kjipuktuk stick were to the success of the March 3, 1875 VSR match. This remains true; however, the Montrealers’ certainly added their own unique twists that night. Let’s introduce their most enduring innovation by moving forward in time, one full century past what was Montreal ice hockey’s first recorded game.

* LASTING IMPRESSIONS

The year was 1985, and I was living in Toronto. It was the NHL’s preseason, and Wayne Gretzky’s Stanley Cup-winning Edmonton Oilers were coming to T.O. What a great opportunity for this westcoaster to see Maple Leaf Gardens! Given what Gretzky was then doing, I was surprised I got a ticket.

Entering MLG for the first time did not disappoint, although I was surprised to see it wasn’t close to full. I think they said I was seated along the “rail.” those seats that bordered the plexiglass surrounding the ice surface. With MLG’s entrance to my left, my seat bordered the neutral zone. There was nobody within a few seats of me in all directions.

It was a generally unremarkable game. Gretzky didn’t play much, as I should have expected. Nonetheless, I have always remembered this game.

Throughout the game, I kept my eyes mainly on the Oiler stars. As these things go, I was forced to note a player who had what hockey fans call a very feisty presence. The Leafs had drafted Wendel Clark the previous spring as the NHL’s number one pick. I didn’t know anything about him, except that he had a large forearm. One of the Toronto tabloids showed him sawing a hockey stick.

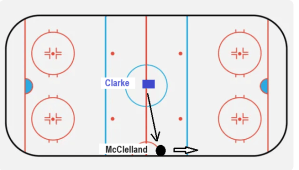

As all fans of NHL hockey know so well, those with Wendel Clark’s playing style make themselves impossible to ignore. And so I had become somewhat familiar with the rookie by the game’s latter stages. There was a gathering across the ice from where I sat. A player shot the puck in the zone to my right. It had pace and would go behind the goalie, staying along the wall. Glancing rightward, I wondered how long it would take to reach me, and then…

THUD!!!

Next came one those rare moments where you recognize a face that you know from TV. Turning to my left, in the direction of the nearby explosion, I saw Oiler tough guy, Kevin McClelland. I’d occasionally thought that he looked kind of like Kevin McHale of basketball’s Boston Celtics. The Edmonton player had very abruptly parked himself directly in front of the seat to my left.

The next thing I knew, another player had entered my periphery. It was Wendel Clark, who must have been about 30 to 40 feet away. I may have noticed as he was slowing down. Suddenly, Clark seemed to realize that the puck was heading toward McClelland. I will never forget the way his eyes lit up then. It told me that the rest of the NHL was beginning to learn: Although wide-eyes, Wendel Clark was NOT a timid rookie.

There was something very expert about the way Clark began his assault, beyond his years, one might say. The way he lowered his stocky frame and charged recalls American football, where an expert defensive player charges an unsuspecting quarterback, unopposed. In football, however, the quarterback tends to go flying into vacant space. Kevin McClelland was driven straight into hardwood and plexiglass. This was one of the reasons why people in Toronto would call their new rookie Captain Crunch.

I had come to Maple Leaf Gardens that night expecting to be most impressed by Wayne Gretzky, and the Great One did have a few moments. But I left MLG having been much more impressed by Wendel Clark and, above all, by the impression he’d made of Kevin McClelland, to my immediate left. In the normal way of thinking, the saying goes, Welcome to the NHL, rookie. Clark had flipped that script. In his case, it was more like, Welcome to Wendel Clark, NHL.

I left Maple Leaf Gardens most impressed by McClelland. Clark’s hit could have easily ended a player’s career. As impressive as the hit was, the way McClelland bounced off the wall was even more impressive. Rather than drop to the ice like a wet teabag, he was throwing off his gloves off! The rage in his eyes matched what I’d seen in Clark, and that’s saying something.

Clark expected this and threw his gloves off almost as quickly. The next thing I knew, the Toronto rookie was throwing haymaker punches a few feet away. Only teenagers can throw that fast for that long, I figure. But McClelland gave back just as good. Both guys hammered each other for what seemed like a long time. As was the custom, the refs allowed the fight to go on for a while before they stepped in and separated the players. The crowd roared with applause, in appreciation of the one with the very feisty presence.

Clearly, these events have nothing to do with Byron Weston’s admonition about “gentlemanly” play in 1860s Halifax hockey. They can, however, be traced to a very specific point in Ice Hockey history, to a small urban neighbourhood that includes McGill University and central downtown Montreal.

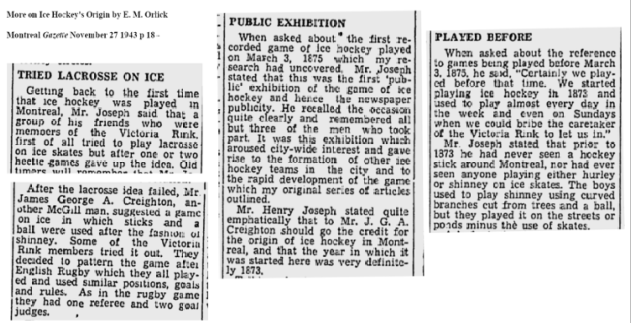

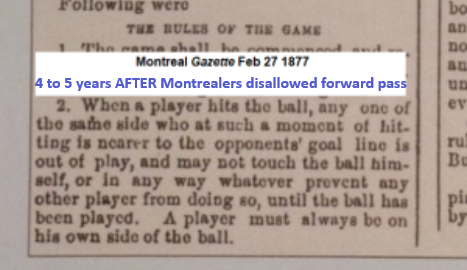

Henry Joseph tells us that the founding fathers decided to make their Montreal ice hockey more like rugby, “soon” after the Halifax transfer. This 1872-73 decision appears to have been first publicly mentioned in 1877, in the Montreal Gazette. Rule 2 of the famous “Montreal Rules” is basically a long-winded saying that the forward pass was not allowed in Montreal ice hockey, in keeping with rugby:

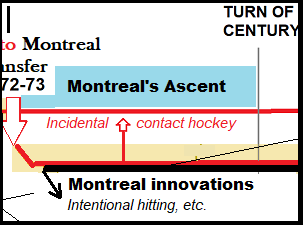

The abolition of the forward pass was one of the first Montreal innovations of the Halifax hockey they inherited by transfer. From the time of the first such innovation, ‘Montreal ice hockey’ became a Halifax-Montreal one in the lineal civic sense. In following the custom of rugby, the Montrealers made the puck-carrier legislated prey. Under certain agreed-to conditions, you could knock a guy all the way back to the 1700s. Two things were introduced through this innovation. The second one was the most enduring and consequential: by getting rid of the forward pass, the Montrealers introduced intentional hitting to Ice Hockey.

* THE ‘ TELEPHONE’ ANALOGY:

The Montrealers created a second unique form of lineal Ice Hockey, or version, that continues to be played today. Their modification crossed a threshold of uniqueness as far as public perception is concerned. This novelty earned Montreal ice hockey a separate identity, one that stood apart from the Halifax game.

To see where we’re going here, consider Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone. Bell lived during an era when others were making telephonic devices. In this analogy, they became non-lineal versions of 19th century “hockey” on ice. Just as Montreal “hockey” claimed the title of Ice Hockey, so did Bell’s telephonic device win the title of telephone – by public acclimation. For decades, others modified Bell’s original invention. Yet for all of these minor tweaks, for well over a hundred years, a telephone was a telephone.

The first mobile telephones hit the market in the late 1980s. For a long time afterwards, there were “telephones” and “mobile telephones.” Eventually, it was no longer clear what kind of telephone was being mentioned in conversations. This led to a reconsideration of Bell’s original invention. It was decided, by public acclimation, that Bell had introduced the landline telephone. The term stuck because it was a quite obvious way of distinguishing Bell’s original invention from the new device.

The mobile phone crossed a kind of threshold in public consciousness, to the point that its modification commanded a separate identity from the landline phone. This significance of the difference explains why it makes no sense to suggest that Bell invented the mobile phone, and why it makes equally bad sense to suggest that the inventors of the mobile phone may have invented the landline phone. We have two kinds of telephones; both are from the same lineage.

In this analogy, Montreal’s hitting hockey assumes the role of the mobile phone. It should compel us to ask what Halifax hockey was, since we know that’s where it came from. If the Montreal game was “hitting” hockey, what is or was Halifax ice hockey?. When we think in these terms, the correct answer is as straightforward as a landline telephone.

Unless we insist on making it the exception rather than the rule, we must assume that Halifax hockey would get quite competitive. Inevitably, there would have been times when Halifax players bumped against each other, just as they do in basketball and soccer. Sometimes the contact would have been a bit too strong. But nothing like the hit Clark laid on McClelland. This is a perfect description of incidental contact ice hockey, is it not? Very clearly, the answer is yes.

If we are to say that Montreal’s intentional hitting hockey is like the mobile phone, then incidental contact hockey becomes the landline telephone of Ice Hockey. It was the original way of playing lineal ice hockey. The introduction of the second version did not make it go extinct. While the landline phone does appear to be on its way out, the same is not true of incidental contact Ice Hockey. It continues to thrive in today’s world, alongside hitting Ice Hockey. Both versions live on which is why we say they are lineal. Although hitting hockey grabbed most of the glory, incidental contact hockey may be the most commercially successful version, when one considers retail sales.

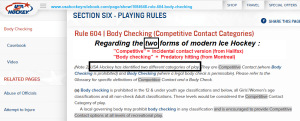

Some people may think I’m muddling lines here, in asserting that there are two different kinds of Ice Hockey. Actually, I’m following a modern convention.

The distinction between predatory intentional hitting hockey and incidental contact hockey is strictly upheld everywhere “organized” hockey is played, and for very good reason. Fence-sitters need only imagine themselves being of it, and on Kevin McClelland’s side of the boards at Maple Leaf Gardens. Or, better, consider USA Hockey’s rule 604. It is one of many examples that will prove there have been two kinds of “organized” Ice Hockey in the modern world since 1873, when the founding fathers of Montreal introduced intentional hitting.

Knowing that there are two kinds of hockey puts us in a much better position to evaluate the famous match at the Victoria Skating Rink on March 3, 1875, and exactly what generated “city-wide” interest in Montreal. Rather than consider only the text, we can read between the lines in a reliable way that provides a richer picture of what took place. The VSR spectators obviously saw a second unique blend of 19th century hockey on ice. Like the first, it was based on superior Halifax technologies. But this second version, Montreal’s invention, included intentional hitting. Both cities’ contributions would have been very novel to those in attendance.

* RADIX STELLARIS HITTEM HOCKEY

What the VSR spectators saw was the version of lineal Ice Hockey that would soon become equated with men’s Ice Hockey in Canada. This introduces a second major player in the story of 19th century Ice Hockey. After moving to Montreal, Halifax’s radix stellaris acquired a bastard sibling, one who made such noise that he simply must be given an evolutionary name. In keeping with our creative use of Latin, we shall give him the formal title: radix stellaris hittem hockeyist. Or, Montreal hittem hockey, or hittem hockey for short.

If you think about it, Montreal’s founding fathers could not have imagined the magnitude of the force they had unleashed. Sigmund Freud would have called it Canada’s collective id. Without realizing it, they had created a version of “hockey” that would eventually require two jails and become Canada’s true national game.

In our opinion, the Montrealers would have succeeded making hockey Canada’s national game even if they didn’t allow intentional hitting. Incidental contact ice hockey can be just as entertaining, as one sees most notably in the women’s international game these days. Many of today’s penalties would exist once the game formalized: minor ones like tripping and interference. Infractions like spearing, cross-checking and elbowing, however seem be the direct result of the need to accommodate intentional hitting. Intentional hitting made what happened on the ice more complicated. It turned out that everybody doesn’t agree on what counts as a clean hit. Others didn’t always like being hit certain ways, even it was legal. Grudges were held. Ungentlemanly things were said on the ice, and off. Throw in that thing about Matilda at the Christmas dance, and circumstances are ripe for escalation.

Abolishing the forward pass and allowing intentional hitting may have been the Montrealers’ very first modifications of Halifax hockey. Whenever the first unique innovation was introduced, dominant 19th-century Ice Hockey (yellowish line) became a mixture of Halifax (red) and Montreal (black) elements. “Accommodation” meant tolerating various “ungentlemanly” behaviours, ones that would have likely led to banishment back in Nova Scotia. Most infractions would eventually result in a ‘sentence’ of two minutes (with the possibility of early release). Fighting got a player five minutes, maximum. This accommodation process seems to explain Clark v. McClelland very well, and countless cases like it. Much of what went down between them was the result of 102 years of evolution, based on the Montrealers’ decision to make their game more like rugby. Predatory hitting “hockey” was imposed on both players as they worked their way up a hierarchical system that included all kinds of minor and junior leagues. Hit or be hit. Hit and be hit.

Those ‘hit’ counts one sees on TV: Each is the progeny of a common ancestor, First Hit, who manifested “soon” after the birth of Montreal ice hockey, and possibly on the same pond. As we cycle through the 2024 playoffs, teams are routinely laying about 15 to 20 intentional hits per 20-minute period, for a total of around 30 to 40 hits per game. They say winning the Stanley Cup is the most difficult feat in sports for a reason. Predatory hitting is a key part of the formula for success. Wear a guy down by slamming him whenever you get the chance. Maybe aggravate an existing injury. Canadians know that playoff hockey is different. It is very Montreal in the evolutionary sense, since it requires the most dominant combination of finesse and power.

In hindsight, by the way, we know that the Montreal game’s immense appeal was never really about abolishing the forward pass. It was about the introduction of intentional hitting. The abolition of the forward pass would last 40 years in elite Canadian Ice Hockey. Hitting hockey continues to thrive 112 years after the former’s extinction.

* 1875 TO 1883

So, after two years, Montreal ice hockey goes from being a clique sport to a game that Henry Joseph says inspired city-wide interest. We can paint a pretty realistic picture of key things that happened there from 1875 to 1883, the time of Montreal’s first Winter Carnival. More Mi’kmaq sticks were ordered from Halifax. The Halifax-Montreal pipeline became a very real thing. More radix stellaris hockey players appeared on Montreal’s ponds, prompting stores to stock Halifax’s skates and sticks prior to winter’s arrival. This rise in local enthusiasm was reflected in the Montreal Gazette’s in 1877 rules.

Montreal’s 1875–83 response to real Ice Hockey reflected what would soon happen across Canada in general. If you think about it, a similar thing must have happened in Halifax starting around 1863, through the marriage of the Mi’kmaq stick and Acme skate. This recalls an earlier point that has been buried by stereotyping much repetition: Halifax ice hockey must have been quite evolved by 1872–73, when it was transferred to Montreal. To suggest otherwise is to make Halifax the exception.

Inevitably, Montreal ice hockey spilled over to nearby communities during this period. This surely followed the Halifax pattern, where radix stellaris hockey reached places like Cape Breton, Kingston, and Windsor prior to the Montreal transfer, after the Acme’s 1863 introduction. As the Montreal region’s organic conversion gained speed, some chose to play pond hockey the incidental contact way. Others preferred intentional hitting.

When it comes to what 1875–83 Montrealers might have called “official” games, however, there may have been only one choice. Knowing this enables us to evaluate Montreal’s first Winter Carnival game of 1883, as we did the 1875 VSR match, beyond textual considerations.

What Carnival visitors saw at that first game, and at every Carnival match that followed until 1889, was a Halifax-Montreal game that was uniquely based on superior technologies and predatory hitting. This wasn’t a version of ice hockey for most Carnival visitors, however. It was a brand-new sport.

* ORIGINS OF THE MONTREAL BIAS

Arthur Farrell was born in Montreal, just two weeks before the publication of the Montreal Rules. Born in 1877, he was just six years old at the time of the first Winter Carnival match. Farrell was a hockey player’s hockey player. He would make himself a Stanley Cup champion. By 1899 Montreal’s conquest of Canada’s frozen waters was basically complete.

All this, less than three decades after the Halifax transfer and before a young nation’s 30th birthday.

* EARLY MYTH CONCEPTIONS

Next, let’s jump ahead to the turn of the century, and read the words of someone who had a bird’s-eye view of someone who witnessed the extraordinary rise of Montreal ice hockey. The author’s credentials are in league with those of Byron Weston and Henry Joseph. We have a freshly minted Stanley Cup champion who, when he wrote this book, was the same age as Creighton was on the day Montreal ice hockey was born.