October 24 2023

by Mark Grant

INTRODUCTION

This is the second of two essays in which we explore the birth and earliest origins of Ice Hockey. In the previous essay we offered a lineal explanation of the birth and early evolution of Ice Hockey, until the end of the 19th century.

We showed how all variations of modern Ice Hockey are derived from a single stick game that became “Canada’s Game” around 1890. That game – which most people think of as Montreal ice hockey – was actually a hybrid stick game that was born in Halifax, Nova Scotia. It must have been born no earlier than 1749, since it required the participation of Halifax ice hockey’s two main partners: the British colonists and local members of the Mi’kmaq First Nation.

This stick game was later transferred to Montreal in 1872 or 1873. There, as a now-hybrid Halifax-Montreal game, it became equated with Canada’s national definition of what “Ice Hockey” around twenty years later. We therefore called this Halifax-Montreal game “the stick game that became Ice Hockey.” His story, Ice Hockey’s story, is like that of a person who winds up living in two cities before he hits the big-time.

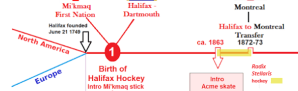

Here is our lineal explanation in diagram form.

The stick game that became Ice Hockey is dentoed by the two red lines in the middle of the diagram which are connected by a circle.

At the far left one sees that this stick game is based on colonial and indigenous stick games. Once born, the stick game that became Ice Hockey first evolves in Halifax, as indicated by the red line on the left of the circle. Moving to the right, it later gets transferred to Montreal (circle with T). There it continues to evolve, as denoted by the red line to the right of the circle.

Continuing in the rightward direction, around twenty years later this stick game becomes Canada’s dominant ‘hockey-like’ game, around 1890. This conquest leads to mass imitation nationwide, as indicated by the various lines and the circles on the far right of the image above. They represent a very small sample of other lineal histories that connect to this singular stick game. Working from there in the opposite direction, all modern versions of Ice Hockey can be retraced to this singular stick game, through a similar series of transfers. But the game they connect to was born earlier, in Halifax, and therefore in Canada and the Mi’kmaq First Nation.

This is Halifax’s or Halifax-Dartmouth-Kjipuktuk’s lineal distinction.

In the first essay we argued that this lineal explanation of Ice Hockey has become eclipsed by a more common and incompatible belief that Ice Hockey was somehow ‘born’ in Montreal in 1875. We showed how the actual 1872-73 birth of Montreal ice hockey proves this “Victoria Skating Rink birther” claim incorrect while pointing to an earlier history of this ‘stick game that became Ice Hockey.’ It confines all relevant pre-Montreal discussions in a singular direction, to Halifax. It does so to the exclusion of all other contemporary stick games which became non-lineal as a result of the Halifax-to-Montreal game transfer. .

Finally, we how Halifax ice hockey’s unique indigenous-colonial makeup falsifies another set of popular beliefs about Ice Hockey’s presumed birth – all of which consider only “Halifax’s” colonial contributors. Accordingly, we also noted that the Mi’kmaq First Nation’s participation in Halifax ice hockey is what secures Canada’s claim for being the literal birthplace of Ice Hockey, a.k.a. “the stick game that became Ice Hockey.” By the same reasoning, we noted, this conclusion must also apply to the Mi’kmaq First Nation.

The rule of lineal evolution is clear: The story of Ice Hockey’s birth is a tale of two nations. This novel explanation has eluded us until now, in no small part, because Halifax ice hockey has become increasingly marginalized in the prevailing zeitgeist of early Ice Hockey. In glossing over Halifax we inevitably gloss over the Mi’kmaq First Nation’s involvement in the Halifax game. This is the key to its uniqueness, and why its birth cannot be explained in exclusively colonial nor indigenous terms: the birth of the stick game that became Ice Hockey had to wait for the two parties to meet up.

A key point in our first essay was is this: The long-eclipsed birth of Montreal ice hockey clears up a LOT of popular misconceptions about Ice Hockey’s true origins.

Still, we’re not quite out of the woods. One more trendy generalization needs to be addressed. In this way of thinking, Halifax’s lineal distinction doesn’t matter, even though it cannot be denied. Its entire pre-1872 legacy is just a big nothingburger.

According to this final generalization, which is usually inferred or implied, James Creighton might just as well have introduced Montrealers to a random stick game from anywhere in England. Or another from Kingston. Or Manitoba, or Pictou – wherever that is. Or Boston, an American city some four hundred miles south-west of Tuft’s Cove. And that’s because Ice Hockey didn’t start to become the game we all know until after the Montrealers got involved.

Pre-1872 Halifax ice hockey was just another “wild and chaotic” stick game. It doesn’t deserve special recognition because Halifax didn’t earn its way into Ice Hockey’s evolutionary stream. It lucked out. All thanks to Montreal.

A quarter-century or so in the making, our last common generalization calls for a practical explanation of Halifax ice hockey’s lineal success.

* ERA 2023’s “SAME GAME” GENERALIZATION

The now-popular belief that all pre-Montreal hockey-like games were the same seems to be the result of three forces that began coalescing just before the turn of the millennium.

The main driver was inspired by the mid-1990s introduction of the Internet. The digitization and widespread circulation of old periodicals from other places proved that the concept of playing a ‘stick game on ice’ was not necessarily a Canadian creation. These new revelations called for a major reassessment of Ice Hockey’s presumed origins.

Meanwhile, the Windsor, Nova Scotia birthplace theory emerged. Widely promoted by Windsorites and local politicians, it became somewhat of a media darling and has remained a go-to source ever since. Then, in 2002 some members of the Society of Hockey Research (SIHR) published a review of the Windsor birthplace claim.

In making their assessment, the members offered a definition of Ice Hockey that was based on two dictionary definitions.

“The wording we have agreed upon, borrowed or adapted from, in particular, the Houghton Mifflin and Funk and Wagnalls definitions, contains six defining characteristics: ice rink, two contesting teams, players on skates, use of curved sticks, small propellant, objective of scoring on opposite goals. Thus, hockey is a game played on an ice rink in which two opposing teams of skaters, using curved sticks, try to drive a small disc, ball or block into or through the opposite goals. (www.sihrhockey.org/__a/public/horg_2002_report.cfm:)

We suspect that this definition of Ice Hockey was of secondary importance to the SIHR members, whose main interest was the Windsor evaluation. Somewhat surprisingly then, over the last quarter-century the SIHR’s definition of “hockey” may have garnered more media attention than the report’s conclusions about Windsor.

We suspect this happened because the SIHR enjoyed strong media connections at Canada’s national level around this time, and a tight relationship with the IIHF which governs Ice Hockey’s international game. Whatever the cause, the SIHR’s 2002 definition seems to have become the preferred way to ‘reassess’ Ice Hockey’s presumed origins in the current era.

* NAMES OF GAMES vs HOW GAMES PLAY OUT

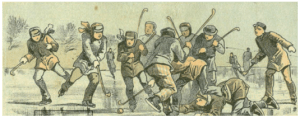

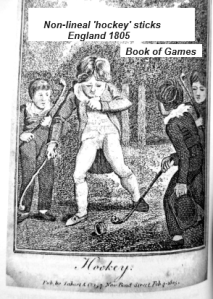

In fairness, one might think that all pre-1872 ‘hockey-like’ games were the same, based on the vast majority of visual evidence that’s been discovered since the Internet’s introduction thirty years ago. The two images on the outside of this three-part panel are quite typical examples of what’s been uncovered over the last quarter-century. Lots of guys with “curved” sticks.

The 1855 London image on the left is described as a ‘hockey’ game. We parked a modern shinty player in the middle panel, in order to ask the following questions:

What game are the players on the right playing, ice ‘hockey’ or ice ‘shinty’? And, what is your level of certainty?

Hard to tell, isn’t it? Welcome to the vague world of 19th century ‘hockey’ evidence. Here’s an 1840s passage from Halifax, where a Mrs. Gould mentions hockey and a game called rickets are mentioned. Where rules of English matter, she is speaking about two different games here, and the point is non-negotiable.

However, five sentences earlier in the same passage, Mrs. Gould says that rickets “is” hockey.

Starting with the first quote, if Mrs. Gould is correct in saying that hockey and rickets are different games, then she must have made some kind of mistake about saying hockey and rickets are the same game five sentences earlier. Or, one can reverse the logic where the latter statement is true. Or – and this is our position – one can conclude that Mrs. Gould’s description is not conclusive.

One conclusive thing that we do know is this: There was a stick game called rickets that was played in Nova Scotia during James Creighton’s childhood. And that stick game most closely resembles Irish hurling on ice, of our British contender games. The following partial description of this version of rickets comes from a reporter who visited Nova Scotia. He wrote it for the Boston Evening Gazette, on November 5th 1859. The whole article can be found here. Byron Weston is about to move to Halifax. James Creighton is nine.

“From the moment the ball touches the ice, at the commencement of the game, it must not be taken in the hand until the conclusion, but must be carried or struck about ice with the hurlies. A good player – and to be a good player he must be a good skater – will take the ball at the point of his hurley and carry it around the pond and through the crowd which surrounds him trying to take it from him, until he works it near his opponent’s ricket, and “then comes the tug of war,” both sides striving for the mastery.”

In Byron Weston’s and James Creighton’s Halifax hockey carrying the puck was expressly prohibited. That’s the one pre-1872 stick ball setting that matters, as we also saw in our first essay. That version of Halifax ice hockey was a different game than the Boston reporter’s rickets.

Next, imagine a world where 19th century descendants of Scots and Englishmen play shinty and grass hockey on ice (which they sometimes called bandy). Which game is this?

We stress the ambiuity because there seems to be a tendency to try and make all pre-1872 Nova Scotia stick games into early forms of Ice Hockey. The image above reminds us that it would not be easy to tell when a game of English grass hockey was being played on ice verses a game of Scottish ice shinty. Likewise, during those stretches when Irish hurling players struggled for possession near goals which were sometimes called rickets – during the “tug of war” phases, when the “ball” was on the ice.

There really is no need to try and make all pre-1872 stick games into one activity, hockey, where these various stick games are all said to be examples of early ice hockey. The societal make-up of Halifax-Dartmouth strongly favours the opposite approach. Over time, ice hockey definitely became the dominant stick game around Halifax in winter. But it wasn’t always the only game played on ice.

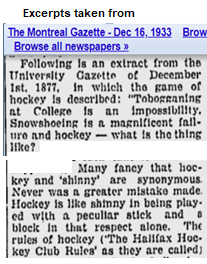

It’s easy to see how the terms shinney and hurley became ways to refer to pond hockey, given their striking relationship to Scottish shinty and Irish hurling. The term rickets was surely borrowed from the game of cricket. From the Irish point of view, naming their ice game after such novel goals may have been a sensible way to distinguish ice hurling from proper hurling which used much larger goals.  We must take care to not grant casual viewers infallible powers of observation, just because the speaker lived during this era. A very early witness to Montreal ice hockey infers that such rushes to judgment was quite predictable even in 1877. Given the era, we should not be surprised. This was a time when many of today’s modern games were becoming formalized, each with its own separate lineal history.

We must take care to not grant casual viewers infallible powers of observation, just because the speaker lived during this era. A very early witness to Montreal ice hockey infers that such rushes to judgment was quite predictable even in 1877. Given the era, we should not be surprised. This was a time when many of today’s modern games were becoming formalized, each with its own separate lineal history.

I take these things to mean that the names associated with mid-19th century games may be less revealing than how they played out, if that can be determined. For the record, the second London image is supposedly of a hockey game. So is the third, which is an 1867 image linked to Boston.

As to how these non-lineal stick games played out: The various raised sticks and short stick-ends in the London and Boston images suggest that there would be lots of hitting and chasing the ball or puck. This would make sense, since 19th century grass fields used for shinty and grass hockey were up to 200 yards in length. Hitting is the only way to best direct a ball in such environments, which requires a short club-like end with some relative degree of thickness.

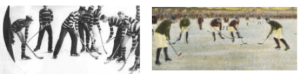

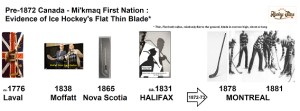

The photos below show examples of lineal sticks. They are ones that have what we called ‘flat thin blades’ in our Hall of Fame nomination essay. This is the stick-end that lives on in modern form.

Both photos also show lineal Ice Hockey, because both photos are from Montreal. Dated to 1881, the left-side image is said to be the world’s oldest Ice Hockey photo. The other is from 1893, and shows a Victoria Skating Rink match in progress. Twenty years have passed since the Halifax-to-Montreal transfer.

Discussed in the first essay, James Creighton’s crucial relationship to Byron Weston proves that the Montreal players are playing an adapted version of Halifax ice hockey. In that stick game, a flat block of wood to be kept on the ice at all times.

We can easily explain why the Montreal sticks attained lineal immortality, versus why the London and Boston sticks did not. Ice Hockey is about trapping, protecting and directing the puck better than one’s opponents on ice. That requires a well-proportioned flat thin blade.

The 1893 VSR photo above is taken from a widely circulated image. The colours of the teams it shows are actually wrong, as are a couple of the players. The image below provides a much better approximation of the teams’ actual colours. It’s a composite photo of a match contested between the Montreal Hockey Club and the Montreal Victorias, who were members of the VSR. It’s a rather historic (downloadable) image. The puck-carrier and his (blue) teammates are either a few days or a few weeks away from becoming one of the very first winners of the Stanley Cup – as we know from the 1893 AHAC schedule.

Judging by the sidelines, there must be well over a thousand people watching what was a regular season game. That’s well up from the 40 or so who attended the March 3, 1875 match. By the time of this photo Montreal ice hockey has claimed the definition of Ice Hockey in Canada. The Stanley Cup’s relationship to the AHAC may have sealed the deal.

* 1860s HALIFAX HOCKEYISTS

By the time James Creighton moved to Montreal – in 1872 or 1873, we go with 1872 for consistency’s sake – the stick game that became Ice Hockey had become linked to an enigmatic organization called the Halifax Hockey Club (HHC). We suspect that the HHC was a somewhat well-organized club, if only because the HHC’s name comes up in multiple stick orders that were made through Creighton’s family business. This may be the result of a sustained spike in consumer demand that began in Halifax-Dartmouth around 1863, we think.

By the time James Creighton moved to Montreal – in 1872 or 1873, we go with 1872 for consistency’s sake – the stick game that became Ice Hockey had become linked to an enigmatic organization called the Halifax Hockey Club (HHC). We suspect that the HHC was a somewhat well-organized club, if only because the HHC’s name comes up in multiple stick orders that were made through Creighton’s family business. This may be the result of a sustained spike in consumer demand that began in Halifax-Dartmouth around 1863, we think.

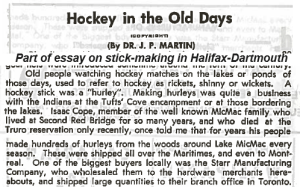

The nearby passage from Dr. John Patrick Martin, ‘Hockey in the Old Days,’ mentions the Halifax-Kjipuktuk stick market as it was a few decades later. The thing to keep in mind, about this era, is that this stick trade involves something much more profound than mere sales. People in Canada are getting turned on to Ice Hockey, for the very first time, and the sticks involved played a major role. Click on the excerpt to find Dr. Martin’s whole article.

The nearby passage from Dr. John Patrick Martin, ‘Hockey in the Old Days,’ mentions the Halifax-Kjipuktuk stick market as it was a few decades later. The thing to keep in mind, about this era, is that this stick trade involves something much more profound than mere sales. People in Canada are getting turned on to Ice Hockey, for the very first time, and the sticks involved played a major role. Click on the excerpt to find Dr. Martin’s whole article.

Looking further into the past, we’ve known since at least 1943 that Halifax ice hockey involved Mi’kmaw players around the time when James Creighton moved to Montreal. This scenario is consistent with Thomas Raddall’s 1948 claim in Halifax: Warden of the North, that Halifax ice hockey, a.k.a. Ice Hockey, was based on interaction with the local Mi’kmaw stick game and its somehow “necessary” sticks.

The fact that the Mi’kmaw played with the colonists around Halifax is very significant, and affirmed in the spilt image above , by Byron Weston in the left-side article. The right-side article quotes the Mi’kmagi, Joe Cope, who affirmed, a few days later, that he played with Weston. Cope’s mention of playing with Weston “and other old players” is also very important, as it infers a setting where Halifax hockey was played on an ongoing basis, which implicates James Creighton by extension. Cope and Creighton didn’t need to know each other, in order to be each familiar with this cradle of Ice Hockey. But they might have. Creighton was around twenty-two when he moved to Montreal, the extroverted Cope was around thirteen.

In the first of these two essays about Halifax, I noted a 1954 letter by Raddall that I had only recently discovered. In it, Raddall mentions seeing “several” references of the Mi’kmaw being seen playing a kind of pond hockey in the latter 1700s and early 1800s, in a playing partnership that began with the “first” settlers.

Raddall’s mention of “several” Mi’kmaw references strengthens the possibility that Weston’s and Creighton’s 1860s Halifax rules may have been based on a unique Mi’kmaq stick that encouraged players to lean downwards, for the primary purpose of sweeping rather than hitting a puck-like object. The prohibiting of raised sticks and carrying the puck may also read like old Haligonian for, “Play your (ice) shinty and (ice) grass hockey and (ice) hurling elsewhere!”

Joe Cope’s involvement in Halifax ice hockey reveals that others could play with Halifax-Dartmouth’s governing class. But surely only if they abided by the rules. Goons did not show up and flaunt the rules in the setting where the Westons and Creightons of Halifax-Dartmouth played. Few would have dared challenge the local authorities during that period in history. A slashing penalty could easily result in jail time, or worse.

But such insubordination was hardly necessary. We know that thousands of people skated around and in between Dartmouth and Halifax in the decades prior to James Creighton’s’ move to Montreal. It sounds like a place where those who wanted to play like the London and Boston players could do so easily, elsewhere. Many would have done so gladly, because their vision of a ‘proper” winter stick game was based on grass hockey or shinty, or a proper game of ice hurling.

All of these considerations seem to suggest that Halifax hockeyists like Cope, Creighton and Weston would have been able to play their gentlemanly game in relative peace. The Mi’kmaq sticks would have also enabled these Halifax hockeyists to evolve their game as well, because flat thin blades provide much greater potential for growth compared to merely curved or crooked sticks. The result would prove to be a better game, as proved by consumer demand.

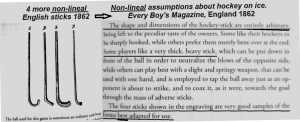

Let’s circle back to the SIHR’s 2002 definition of hockey. Since it makes no distinction between playing sticks in its definition of Ice Hockey, it must follow that the 1805 sticks seen nearby are “the same” as Halifax’s entire pre-Montreal inventory. Likewise with four the 1862 English sticks shown below. The author who refers to them tells his English audience that one’s preferred stick-end is “entirely arbitrary.”

Let’s circle back to the SIHR’s 2002 definition of hockey. Since it makes no distinction between playing sticks in its definition of Ice Hockey, it must follow that the 1805 sticks seen nearby are “the same” as Halifax’s entire pre-Montreal inventory. Likewise with four the 1862 English sticks shown below. The author who refers to them tells his English audience that one’s preferred stick-end is “entirely arbitrary.”

It should be mentioned that the four sticks are likely intended for grass hockey. We show them only because they are offered as early ice hockey sticks. This supports our final generalization, in which all pre-Montreal versions of hockey are said to be “the same.” It is a logical conclusion, based on the SIHR’s 2002 definition of hockey. Yet it turns out to be an illogical conclusion when all of the pre-Montreal stick inventory is considered. And that’s partly because these four sticks are not “the same”…

… as this stick…

THE 19th CENTURY “HALIFAX TAKE-OVER”

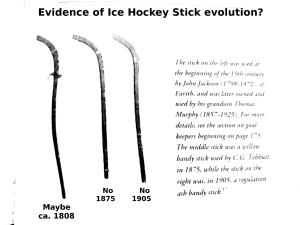

* 1 of 3 – ICE HOCKEY’S REVOLUTIONARY STICK

Shown in the preceding image, the Moffatt stick was presented to the public after the SIHR offered their 2002 definition of Ice Hockey. So were two others in the following years, the Walker and Laval sticks. We consider all three to be “the same” because each features a relatively well-proportioned, flat thin blade. In practical terms, its not difficult to see how such a device became “dominant” on frozen ponds and lakes, eventually resulting in mass extinctions of the “curved” stick. After all, Ice Hockey is about trapping, controlling and directing a puck better than one’s opponent.

Since Montreal ice hockey claimed the national definition of Ice Hockey, and partly through Halifax ice hockey‘s flat thin blade, a very significant question follows: Who introduced the flat thin blade to Halifax ice hockey?

Since we’re talking about the lineal story of early Ice Hockey, there are two continents to consider.

1 of 2 – EUROPE-BRITAIN

The flat thin blade could have been imported to Halifax from Europe. The earliest European-British flat thin bladed stick that we know of was owned by one John Jackson who was born near Cambridge, England. We’ll call his device the Cambridge stick and date it to Jackson’s 10th birthday. Seen on the far left of the image below, Europe’s and Britain’s oldest ‘flat thin’ blade dates to around 1808. This is well before the Halifax-to-Montreal transfer of 1872-73, meaning that such an European stick could have reached Halifax before then.

In the Cambridge stick’s case, we have no Henry Joseph-like proof of transfer. That would be ideal, if one wanted to make the argument that the English introduced the flat thin blade to Halifax ice hockey. Nor do we have any testimony where Jackson writes that he or a colleague personally delivered the flat thin blade to Halifax-Dartmouth. Nor do we have any other English claim to that effect. It’s only possible in theory that an English flat thin blade could have made its way to Halifax, before James Creighton moved to Montreal.

In having no specific claim to address, we must try to make the best generalization as to how the Jackson stick could have merged with pre-1872 Halifax ice hockey. Then we must also ask if the interpretation seems strong or weak, because not all generalizations are equal.

Cambridge, England is said to have been involved in Bandy’s evolution prior to that game’s formalization at Oxford in the late 1800s. Cambridge and Oxford are also home to two of England’s finest schools, where English military officers were often educated. We also know that stick ball on ice was played at Lord Stanley’s Eton before 1872.

For reasons discussed, the Cambridge stick’s flat thin blade would have made quite an impression in English settings where others used curved or crooked ends. We should therefore expect that it inspired some degree of imitation, and not be surprised if a future officer later introduced the flat thin blade directly to Halifax-Dartmouth through this kind of organic process. Such a process would apply to other sticks from the same region, in theory, if they were found in orbit of England’s officer schools. To our knowledge Jackson’s is the only known English stick that features a flat thin blade, prior to the Halifax-to-Montreal transfer. Still, we find it very plausible that the Cambridge prototype could have reached Halifax.

Ironically then, when we apply the same logic going the other way across the Atlantic, it must become equally plausible that the Cambridge stick was inspired by a Mi’kmagi-Canadian prototype! Keep in mind that British officers would have begun returning from Canada to Britain not long after 1749, fifty years before Mr. Jackson was born. If we are to assume that British officers brought their sticks to Canada, we must also presume that some may have taken Mi’kmaq sticks back to England, especially given the Mi’kmaq stick’s exceptional reputation. There’s a very legitimate possibility that the Mi’kmaq stick played a significant role in the evolution of Bandy, or in England’s migration from grass hockey to ice hockey.

It’s possible, of course, that the flat thin blade emerged in Bandy and Ice Hockey independently, free of the other’s influence.

2 of 2 – MI’KMAQ NATION – CANADA

The oldest prototypical Ice Hockey stick-end hails from North America, not Europe. Found in eastern Canada and what is Mi’kmaq territory, the Laval stick may be the most important relic in the history of early Ice Hockey. In our previous essay, we argued that it was almost certainly used to play two stick games – the Mi’kmaw’s oochamkunutk and, as a result of a trade, also the colonial ‘stick game that became Ice Hockey.’ The fact that it was universally described as a ‘hockey’ stick only, its a reflection of the still-lingering colonial only bias.

We think that it was used for both games because of the Laval stick’s age. Scientifically dated to 1776 +/- 20 years. At the very youngest (1896) it precedes the birth of Cambridge’s John Jackson by a few years. Going to the other extreme, it could been crafted less than a decade after the founding of Halifax. But as these things go, the normal curve of distribution predicts that the Laval stick most likely dates to the middle of said range, or closer to 1776.

We feel that the evidence strongly favours Mi’kmaw provenance. It is possible that the Laval stick could have been made by a colonist, during the quarter-century or so that followed 1749. If this is true, perhaps we have some record of the British settlers using steam compression to make their hockey sticks. The Mi’kmaw seem to enjoy a reputation as advanced wood workers. The Laval stick seems to reflect this belief.

The Mi’kmagi story-teller, Jeff Ward, described an ice game that involved a stick that Ward likened to today’s “hockey” stick. Here we mention, again, that there’s a difference between the stick game and what it was called. The Mi’kmaq presence in eastern Canada precedes England’s Stonehenge by several thousand years. That’s plenty of time make a winter stick game on ice and discover the “necessary” nature of the flat thin blade.

Our own behavior says we must expect that the Mi’kmagi players kept the flat thin blade once it was introduced. Such a device could have been produced anywhere in the vast Mi’kmagi territory which covers much of eastern Canada. It’s very easy to see how the Laval stick’s flat thin blade could have eventually reached the Mi’kmaw at Tuft’s Cove and Lake Micmac. This is another excellent generalization, regarding how the flat thin blade could have entered Halifax prior to the Montreal transfer. Given the Mi’kmaw’s strong presence in Halifax, and their known involvement in stick-making we consider this to be the most plausible explanation.

The Laval stick’s owner, Brian Galama, linked it to Canada’s colonial military. This is exactly the kind of thing that we should find, according to the Order of Canada historian, Thomas Raddall.

However, I was unable to reach Mr. Galama while writing my previous essay. So the only thing that seems certain about the Laval stick is its age. This proves the oldest North American flat thin blade is older than the oldest one from Europe.

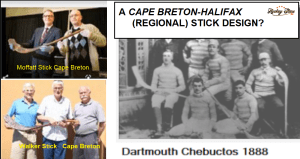

* A CAPE BRETON – HALIFAX REGIONAL CONNECTION ?

Cape Breton, Nova Scotia’s Moffatt and Walker sticks provide a much more certain geographical relationship to Halifax, than does the Laval stick. We’re mainly interested in the Moffatt stick because it too has has been scientifically dated, to 1835-38. This proves that the flat thin blade was near Halifax for more than four decades before James Creighton moved to Montreal.

The idea of a Cape Breton-to-Halifax stick transfer (or vice versa) is also extremely plausible. Cape Breton’s Moffatt and Walker sticks also display design standardization, and a definite commitment to the flat thin blade. We also don’t know who made these sticks, although both emerged near another Mi’kmaw settlement. As we noted in our first essay, this raises the strong possibility that the Moffatt and Walker ‘hockey’ sticks were also used to play oochamkunukt. Going one step further, it’s hard to argue that the Dartmouth Chebuctos’ 1889 sticks weren’t cut from the same mold.

Are these similarities evidence of a regional stick design, and a commitment to the flat thin blade which infers a somewhat evolved understanding of ice’s unique requirements?

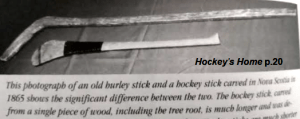

One important detail is clear, the Moffatt-Walker-Chebuctos stick design would have been well-suited for Byron Weston’s 1860s Halifax ice hockey. Martin Jones links the stick below to Nova Scotia and the year 1865, in his book, Hockey’s Home – Halifax-Dartmouth. Once again, one sees a relatively well-proportioned flat thin blade.

As with the Moffatt stick, the “Nova Scotia” stick puts us close to Halifax, but not quite there.

It would be most ideal if we could link a proper flat thin blade directly to pre-1872 Halifax. This recalls what we called the rule of 1872 in our first essay. In order to merge with Ice Hockey history, a given 19th century or early thing must either attach itself to Halifax before 1872 or to Montreal after 1872. In our opinion, this is what Jones does on page 54 in Hockey’s Home with respect to the hockey stick. He shows a silhouette of a boy holding what appears to be a hockey stick. Dated to around 1831, I placed the image alongside another that appears on the same page. The other image shows Steven Coutts holding an old hockey stick from the Nova Scotia Hockey Hall of Fame.

This deserves pause. Martin and Coutts have literally proved that a real-life old hockey stick provides an excellent resemblance to the 1831 silhouette stick. This is the earliest direct evidence of flat thin blade merging into Ice Hockey’s lineal evolutionary stream, and the evidence points to Halifax to the exclusion of all other settings. The ca. 1831 Silhouette Kid recalls Mrs. Gould’s assertion that 1840s hockey and rickets were the same. According to that interpretation, the Silhouette Kid’s stick was used to carry a ball in competitive environments. What an impractical suggestion. So was the Moffatt stick, according to the same logic. Hardly likely, we say, for practical reasons

The Silhouette Kid’s stick provides excellent cause to believe that Halifax transferred the flat thin blade to Montreal, through our own behavior. We have kept the flat thin blade ever since its introduction. We must presume that the players in Halifax kept the flat thin blade once it was introduced, setting the stage for Creighton’s first order of Montreal sticks.

For the record, not everyone agrees that the silhouette shows a hockey stick. The authors of On the Origin Hockey wrote that they remain unconvinced, even though must have seen the Jones-Coutts match. Merely expressing doubt is the easy part. The authors didn’t offer any alternatives as to what it could be. Whatever it is must sure like a hockey stick.

The Silhouette Kid’s stick suggests, on the balance of probabilities, that the flat thin blade entered Ice Hockey’s evolutionary stream prior to the Montreal transfer. The Moffatt stick supports this in a corroborating way.

The “flat thin blade” goes a very long way to explaining, in practical terms, why ‘the stick game that became Ice Hockey’ conquered Canada on its way to becoming a global sport. But it doesn’t go all the way.

And that’s partly because this skate….

is not ‘the same’ as this skate :

* 2 of 3 – ICE HOCKEY’S REVOLUTIONARY SKATE

I’ve often felt for Dartmouth during this investigation, knowing what it’s like to endure being perpetually in the shadow of a big brother who too often gets all the credit for things he doesn’t deserve. It’s long been said, for example, that the last non-NHL team to win the Stanley Cup did so in Victoria, British Columbia in 1925. That episode took place in nearby Oak Bay, ladies and gentlemen. West-central Oak Bay, in fact.

Not that I’m any better, given how I keep squeezing Dartmouth of the local equation every time I use Halifax-Kjipuktuk. If it’s any consolation then, we consider Dartmouth to be Halifax-Dartmouth-Kjipuktuk‘s most luminous star.

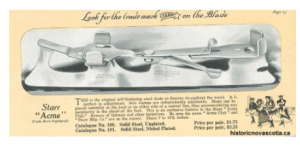

We say this because our conclusion is that the Kjipuktuk Mi’kmaw ‘almost certainly’ introduced Ice Hockey’s flat thin blade, and ‘very plausibly’ did the same in English Bandy. We ‘know,’ however, that little brother Dartmouth revolutionized the World of ice skating. And this must mean that the Acme skate ‘definitely’ revolutionized Ice Hockey and Bandy.

The story goes like this. Until around 1863, people used skates that strapped on to the user’s shoes or boots, like the one seen in the first skate photo above. That all changed in Dartmouth around 1863 when the Starr Manufacturing Company began rolling out the Acme skate, which is seen in the next image. The Acme is said to have been the invention of Thomas Bateman and John Forbes. T

With this in mind, lets revisit that newly discovered evidence of hockey-like games that’s been uncovered since the Internet’s introduction, namely the entire portion that precedes the Acme skate’s introduction around 1863. Whether they appear in images or stories, like the 1797 English engraving seen nearby: all such players were using non-lineal ‘strap-on’ skates. Such skates became evolutionary also-rans as soon as the Acme skate hit this ice. And they remained evolutionary also-rans afterwards, in a storyline that also with their collective extinction. So no, not all pre-1872 skates were not “the same” either.

With this in mind, lets revisit that newly discovered evidence of hockey-like games that’s been uncovered since the Internet’s introduction, namely the entire portion that precedes the Acme skate’s introduction around 1863. Whether they appear in images or stories, like the 1797 English engraving seen nearby: all such players were using non-lineal ‘strap-on’ skates. Such skates became evolutionary also-rans as soon as the Acme skate hit this ice. And they remained evolutionary also-rans afterwards, in a storyline that also with their collective extinction. So no, not all pre-1872 skates were not “the same” either. It’s often been said that Acme skates revolutionized skating because it clamped on to one’s shoes. For that reason they were sometimes called spring skates. All true, but we refer the Acme as the world’s first levered or leveraging skate, as this provides a more direct sense of its relative-evolutionary advantage. The Acme skate introduced the idea of “enhanced leverage” which has been preserved and improved upon ever since. The leveraged skate empowered the user by enabling him to leverage his foot much more effectively than with strap-on skates. It also enabled its user to leverage his legs and leverage torso. All of this meant that the Acme user could leverage the ice to a significantly higher degree. As this translated to Ice Hockey, it made a player better at directing and protecting puck-like objects.

The practical explanation in this second essay says that ‘the stick game that became Ice Hockey’ did so by conquering Canada’s frozen ponds and lakes through the application of two Halifax technologies. For the most part, this Halifax take-over was subversive in nature. To see how it must have played out in many Canadian communities, Henry Joseph would have needed to do only one thing, after he took one of Montreal’s first Mi’kmaq sticks:

Look down at his feet.

Keep in mind that the revolutionary Acme skate had been around for ten years before the birth of Montreal ice hockey. All the founding fathers were already Starr skates. Or, they were wearing skates ones that mimicked Dartmouth’s now-indispensable principle of enhanced foot leverage.

This is exactly what happened in the wider market. It’s been said that the Starr Manufacturing Company sold 11 million pairs of skates, from the mid-1860s until the Great Depression crushed that market in the 1930s. This must the smaller part of Dartmouth’s legacy over the same period, because revolutionary technologies inspire mass imitation. We should probably not be surprised if other skate-makers had produced 100 million leveraged skates by the 1930s.

We believe that Canada’s introduction to real Ice Hockey was quite organic. One by one, Mi’kmaq sticks and Acme skates would find their way from local stores to Canada’s frozen ponds and lakes. Their presence would inspire imitation everywhere. At first, all the cool kids had Halifax skates and sticks. Then it became uncool not to have them. Then, the louder personalities began to question your right to play with outdated gear. Then, you allowed yourself to become assimilated. Or, you went extinct. This is what we mean by the subversive “Halifax take-over.”

This picture above tells you much about the world that James Creighton grew up in in the 1860s. It’s the inside of the Halifax Skating Rink (HSR) which opened in 1863. Weather and time permitting, on a day when the HSR was that crowded, one can be confident that thousands of people would have been skating around greater Halifax – Dartmouth, James Creighton included:

The Halifax Morning Chronicle, February 15, 1855: “The skating on the Northwest Arm was very fine yesterday, and the ice was thronged with skaters, both ladies and gentlemen. There were several thousand persons on the ice, and the scene was one of great animation.”

The Novascotian, February 22, 1860: “The skating on the Northwest Arm was very fine yesterday, and the ice was thronged with skaters, both ladies and gentlemen. There must have been several thousand persons on the ice, and the scene was one of great beauty.”

The Halifax Evening Mail, February 14, 1872: “The skating on the Northwest Arm was very fine yesterday, and the ice was thronged with skaters, both ladies and gentlemen. There were estimated to be at least 10,000 persons on the ice, making it one of the largest skating crowds ever seen in Halifax.”

Reports like this remind us that Halifax-Dartmouth was a very vibrant community on winter days when people could gather. The Silhouette Kid (1831) and the Moffatt stick (1835-38) remind us that Ice Hockey’s revolutionary stick was in use, in and near Halifax, for four decades prior to the opening of the HSR.

As for skates, in Thomas Raddall’s account of early Ice Hockey, we are told that the Halifax and Dartmouth officers preferred Mi’kmaq sticks yet not strap-on skates. Could this be because it is easier to play hockey on ice in boots versus strap-ons?

There’s a very testable question.

Or, did the officers finally go with skates after 1863, because of the Acme’s relative advantages? We noted how Weston and Creighton were part of the social elites. Chances are very good, that they and others in their group would have had privileged access to some of Starr’s earliest Acme orders.

* 3 of 3 – ICE HOCKEY’S REVOLUTIONARY PLAYER

For winter sporting enthusiasts in wintry Halifax-Dartmouth, the 1863 era would have been a time of noticeable change. But the Acme skate and the brand-new indoor skating facility were not the only major changes afoot. A new kind of hockey player was emerging amidst all of this change – or what they used to call hockeyists. Charles Darwin would have liked this specimen, for he would go on to become 19th century stick ball’s dominant player based on two competitive advantages. Given his grand evolutionary distinction, we will give this species of hockey player a formal name. We shall call him Radix Stellaris Halifax Hockeyist. Or radix stellaris for short.

Radix come from Latin for root, in recognition of the Mi’kmaw’s flat thin blade which was literally cut from a tree’s roots. Stellaris, Latin for star, is a nod to Dartmouth’s Starr Acme skate.

A radix stellaris hockeyist is a hockey player who used both of these revolutionary Halifax technologies, the Amce skate and the Mi’kmaq stick.

* CREIGHTON MAN – e.g. radix stellaris 10.0

It must have sucked, when that first winter came in Montreal. Colder weather had always portended ice hockey. So, when the bad weather kicked in, there always much to look forward to. James Creighton was probably surprised to learn that nobody around Montreal played Ice Hockey. He may have seen an ice shinty game or two when the first ice came. But like Henry Joseph said, that was not the same thing.

Then came the lacrosse-on-skates experiment. Creighton thought a lot about Halifax hockey during that “hectic” occasion. He wasn’t entirely unpleased when he saw that the majority didn’t think the lacrosse thing was going to work. His decision to suggest another game would alter the course of Canadian sporting history.

There would have been no need place an order for Halifax sticks by pony express. In 1872-73 it would have been a short walk to any telegram office. In such a place our son of Halifax may have placed an order to his grandfather’s company, the James G. A. Creighton and Son ship chandling and wholesale food business. Perhaps they had some sticks on hand, during this early phase of winter. If so, they might have ship from Halifax to Montreal the very next day. Alternatively, Creighton may have mentioned a name or two of some Halifax Hockey Club members, as we know that mentioning the HHC later became his custom when placing orders. Maybe an HHC member fetched the sticks from a local Mi’kmaq settlement instead. Or, they could have made arrangements for a special order through the setting where Mi’kmaw players like Cope played with Weston and others.

There would have been no need for Creighton to involve others when the sticks arrived in Montreal, at least not the entire group. We guess that he ordered two or three dozen sticks. If he didn’t hire someone to take the sticks to his home, he may have asked one of his new Montreal friends to accompany him, maybe two. With everything being in walking distance in 1872-73, Montreal’s first sticks may have been stored at the VSR. Only then could he suggest a firm day or two, when it was most likely that the others could gather in the greatest numbers. Assuming that 1872-73 society is like our own, that would have meant meeting up on a weekend or holiday.

Let’s return to the birth of Montreal ice hockey, but this time at the part where around two dozen young guys are still lacing up. Every one of them has taken one of Montreal’s first ice hockey sticks. There’s a pile of extra sticks nearby, and some wooden pucks that Creighton also ordered.

While everybody is getting set up, James Creighton – who came early – decides to go for a warmup. He starts going in one of those counter-clockwise circles that one sees before games, with a stick and puck.

A few of the founding fathers look on. It’s no surprise that Creighton’s a very good skater. And he’s not the only very good skater in this group. What stands out immediately, is how he uses his stick to control the puck thing. He shifts the stick over the puck to either side with steady rhythm. Left, right, left. The puck obeys his every movement, moving along with him as he carves circles into the ice. This is the Montrealers very first introduction to stick-handling.

It is one of many things that Creighton will show them, and sell them on, on this most historic day.

Left, right, left, right, left… As ten years of cellular memory starts to come back, Creighton Man feels that special twinge in his legs where he wants to bust out of himself. Unable to contain himself, he lays down his first Tuft’s Cove twist of the season. The Montrealers are quite blown away. Then Creighton starts skating backwards. The puck follows him like a puppy dog. Left, right, left, right…

Now skating forward again, Creighton eyes Henry Joseph who stands by the pile of unused sticks. Without breaking stride he snaps a wrist shot, from around twenty feet away. The wooden puck sails between Joseph’s legs.

Creighton bites into the ice with his Acme skates. He tells Joseph to send another one of the pucks back to him, “With some speed, just like I did,” he says. Joseph, an athlete, makes a pretty good first attempt. But he tries hitting the puck, having failed to notice that Creighton Man actually swept it in his direction. And so Joseph’s blade hits the ice before contacting the puck, changing the impact angle. The errant puck goes about twelve feet to Creighton’s right. This is not a problem. Our radix stellaris does a couple of chop steps then glides towards the still-moving puck. With his flat thin blade out well out to his side, he sweeps the puck forward then brings his hands together and it’s left, right, left all over again. . .

We may think that we know this scene. An advanced person shows up at a gathering where total beginners are. We know how this translates in Ice Hockey (today). In today’s world, beginners step onto the ice because they’ve seen Ice Hockey and want to become players. The founding fathers of Montreal ice hockey had no such prior frame of reference. Nor had those who watched the city’s Winter Carnival games from 1883 to 1889.

What the founding fathers of Montreal ice hockey saw in Creighton should explain why one stick game became associated with Ice Hockey in Canada and beyond. In this practical way of thinking, Creighton didn’t just transfer a game based on certain rules. He also transferred some of the sizzle of Halifax ice hockey, which was mainly about what the Acme skate and Mi’kmaq stick could do in combination. The marriage of these technologies marked the birth of the dominant version of Ice Hockey, as indicated by the gold bar on our unfolding timeline. This was radix stellaris hockey, which must be considered in the widest possible terms, where players around the world play versions of “hockey.” Halifax had been playing hockey this way for ten years by the time Montreal had their first look.

What the founding fathers of Montreal ice hockey saw in Creighton should explain why one stick game became associated with Ice Hockey in Canada and beyond. In this practical way of thinking, Creighton didn’t just transfer a game based on certain rules. He also transferred some of the sizzle of Halifax ice hockey, which was mainly about what the Acme skate and Mi’kmaq stick could do in combination. The marriage of these technologies marked the birth of the dominant version of Ice Hockey, as indicated by the gold bar on our unfolding timeline. This was radix stellaris hockey, which must be considered in the widest possible terms, where players around the world play versions of “hockey.” Halifax had been playing hockey this way for ten years by the time Montreal had their first look.

We have no idea if Creighton was one of the best players around Halifax prior to when he moved to Montreal. But we can be sure that the best players there must have been Ice Hockey’s first world-class players, and must have because of the sticks and skates they used in combination.

There seems to be a consensus view that our former skating judge was a competent skater from a very early age. As a 22-year old sports lover, we presume Creighton to have been a highly evolved radix stellaris 10.0, or such a player with ten years experience using the Mi’kmaq stick and Acme in combination.

Therefore, if our Creighton Man didn’t start greatly impressing the others during warmup, he simply must have during Montreal’s first Ice Hockey game. This must be the result when a hockey player with ten years experience steps onto the ice with total beginners who have never even seen a hockey stick, let alone thought about using one. Let’s say that each Halifax winter is 100 days, and that Creighton played ice hockey for an average of 1 to 3 hours a day, as a radix stellaris hockeyist. Over a decade Creighton has played 1,000 to 3,000 hours.

The other founding fathers didn’t call our 10.0 Stelly, Rad-man or even the Great Creight – our personal favourite – but they must have regarded Creighton as the Evolved One and a role model worthy of imitation. We know this because James Creighton did in fact sell this group on Halifax ice hockey. It was the “selly” of the century, given what followed in Montreal.

Basically, James Creighton turned all of his new chums into radix stellaris hockeyists, thereby making them direct descendants of his former tribe. This kind of replication says much about Ice Hockey’s true proliferation. The formalization of Ice Hockey, through things like the AHAC and the Stanley Cup, was very much a celebration of this unique kind of hockey and hockey player.

This is our practical explanation of Halifax ice hockey’s success. All three of the partners were well-presented on the day when Montreal ice hockey was born, in other words. It took a son of Halifax to show what can be done with Dartmouth skates and a Kjipuktuk stick.

To our final generalization, where all stick games are treated as the same until Montreal got involved: Halifax most certainly did earn its way into Ice Hockey history. Frankly, if it wasn’t for Halifax ice hockey’s skate and stick, the Montrealers would have nothing to show their neighbours at the VSR on March 3, 1875, other than yet another non-lineal stick game based on crappy sticks and even crappier skates.

Instead, eighteen radix stellaris hockeyists were able to turn Montreal onto this version of hockey two years later, on March 3, 1875, and only only as 2.0s. Some who played in Montreal’s first Winter Carnival in 1883, may have been 10.0s just like Creighton Man was on the day of the Halifax-to-Montreal transfer.

For reasons like Winter Carnival, many would say that Montreal was the rock star of 19th century Ice Hockey. We would agree, while adding that Halifax must therefore be its roadies par excellence. The partners handled the retail end of Ice Hockey’s first national tours, which were mainly about a young nation’s unceasing demand for their gear.

It would not be unfair to say that the partners’ legacy became buried by their own success. Like I had suggested at the start of the first essay, the story of Halifac ice hockey, before and after the birth of Montreal, may be early Canada’s greatest untold story.

CONCLUSION

The image I would like to leave with the reader has two parts. It involves Creighton skating around with a stick and puck (or ball) on the day when Montreal ice hockey was born, as the experienced player we know he was. Just as importantly, our last image includes his audience, of total newbies.

The onus has shifted. Those who would still suggest that strap-on skates are or even might be “the same” as Acme’s should make their point on ice, if they wish to be taken seriously. Likewise with others who might suggest, for example, that those four sticks we showed are or might be comparable to the Moffatt stick.

Good luck with that.

Then again, there is the theatre of ideas, and the theatre of ice. Strong expectations aside, we will never “know” if this practical explanation is really true until it gets tested on ice. In the end, the better question will likely involve figuring out how much better the Halifax technologies than other skates and sticks.

I just thought I’d float that idea before closing. It’s an idea that can be taken up any time, if people are interested. Maybe one day some people will consider reviving the Halifax Hockey Club, so to speak, and resume production of 19th century skates and sticks.